Journey for Peace: His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama

Photographed by Manuel Bauer

with text by Matthieu Ricard and Christian Schmidt

Zurich: Scalo Press, 2005

291 pp.; $49.95 (cloth)

The Fourteenth Dalai Lama has, rather quickly, become one of the most visible figures on our planet and, in the process, one of the least seen. We are all familiar with his warming smile, the image of his head thrown back in laughter, the beaming alertness with which he picks out a friend in a crowd, or waves to ten thousand people in a rock stadium as naturally as if to a fellow monk across the road; but the suspicion always remains that the more we see of his face, the less we will make of it, and the less alive it will be to us. As children in the Zurich streets around me, while I write this, hearing of an approaching celebrity, bounce on their fathers’ shoulders, shouting, “Dalai Lama, Dalai Lama,” as cities get flooded with images of the steadying face, it’s easy to feel that the real power and uniqueness of the presence will get diluted, until, like the Taj Mahal, say, it will seem more of an icon than a reality with the capacity to transform.

This feature—a symptom of the Age of Celebrity crossed with the Age of the Image—becomes doubly acute when you are dealing with a monk, and a Buddhist monk at that. The Dalai Lama is speaking, as much as anything, against surfaces and screens and projections, and for precisely those causes and conditions that can’t be seen. He famously took photographs when young himself, in the Potala Palace, and is always ready to accept images, like anything, insofar as they are “beneficial;” but a picture of a Buddhist teacher can seem, in the larger scheme of things, like a depiction of a finger pointing at the moon, no more substantial than a drawing of a sutra. The Dalai Lama has the rare capacity to speak with his being, his face, his eyes—to make his movements his message, in a way—and yet all the posters and postcards and buttons of him that fill the world seem always to speak for the effect and not the cause; what he is keen to show us is not so much his face as all that lies beneath it, which is, by definition, out of view.

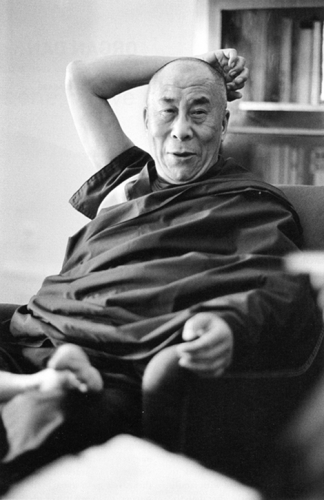

It is deeply moving, therefore—a revelation, in fact-to come upon the first book that I have seen, in words or images, that somehow seems to catch the Dalai Lama in all his lights and moods—in his unvarnished reality—and, beyond that, goes deep into the heart of a life that, by definition, mostly takes place far from public sight, behind closed doors, at those moments when no eyes are watching. Manuel Bauer, a Swiss photographer, won the trust of the Dalai Lama many years ago, in part, perhaps, because he was the first photographer to accompany Tibetans—a father and daughter—and chronicle their flight across the Himalayas from Tibet to freedom (a story that leaves tears in his eyes when he recounts it even now); as a result, he became the first photographer allowed to follow the Dalai Lama at almost every moment of his day, in his bedroom, in his meditation chamber, while he is alone with his aides, for more than three years, shadowing him on more than thirty different tours. The result is surely the most intimate and objective account of this mysterious being that we’ve seen yet, which somehow becomes as various, as shifting, and as stirring as the man it chronicles.

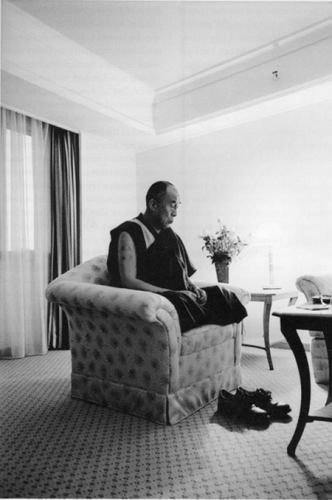

A journey for peace is, in the Dalai Lama’s way of thinking, a journey inward, toward that center where we cultivate an inner peace; it is not just an external journey, to Croatia and Bodh Gaya and Washington, D.C. (all fully covered in this book), but, more fundamentally, a journey into that changeless core that lies inside us, a journey, you could say, into meditation. Bauer’s Journey for Peace begins, therefore, with a quite literal pilgrimage: a series of images of cars trailing down a mountainside, crowds assembling, faces glowing with expectation, a convoy approaching, and then, at last, the Dalai Lama emerging into the midst of the souls that have been waiting for him. Yet it concludes, two hundred pages later, with an extended series of black-and-white portraits of the Dalai Lama during his morning meditation, page after page of the sturdy face with eyes closed, far away, in the realm, it might seem, of nonbeing, each picture almost identical to the one before, and yet marginally different. The Dalai Lama moves a lot when he’s in meditation, Bauer reports; his book is, as much as anything, about the movements that happen within stillness, and the stillness that lies at the core of movement. The last image in the book, in the classical Buddhist tradition, depicts just a pair of sandals on the ground.

In the meantime, though, the images—now black-and-white, now color; now taking up an entire page, now lined up in tiny rows, as with pictures from a street-side photo booth—move constantly back and forth between the Dalai Lama that we see and the one that most of us will never see, between person and personality. The switches between them become almost the book’s subject (an expert on facial expressions has said that the Dalai Lama passes through more expressions more quickly than any subject he’s observed in thirty-five years of professional scrutiny: delight, gravitas, abstraction, keen attention play in constant succession upon his face like light upon some water, themselves an illustration of the impermanence he speaks about). Thus we see the Dalai Lama here trying on hats in an airplane, extending himself to a woman who can’t see, sometimes looking intent and even drawn, sometimes bright-eyed (as he talks to Muslims in a mosque). But we also see him confronted with a woman in a trance, attending his state oracles as they go through convulsions, being mobbed by crowds of delirious Mongolians who, unlike Tibetans, believe there is a merit in just touching their beloved leader. The book is not simply about the man, but about the world he occupies and the world that awaits him: many of the images are just of crowds—of the hopes and needs many people bring to the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, in effect—of cameras, of the vast auditoria where the Dalai Lama becomes a tiny figure dwarfed by the screens on either side of him.

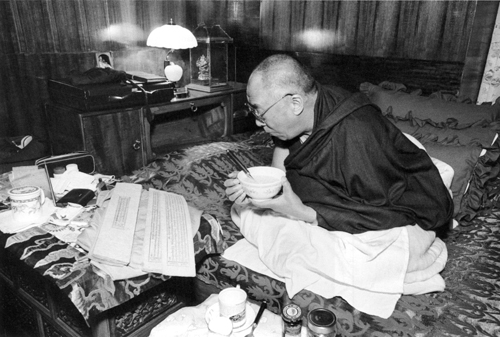

Screens are everywhere in this book, as if to show us the man of our projections, always in quick contrast with the man as he gathers himself in private (eating his breakfast as he considers a sutra, walking on his exercise machine in the morning, taking private instruction from a teacher of his in Dharamsala); the public figure here shown with Lech Walesa, Mikhail Gorbachev, Vaclav Havel, addressing the European Parliament, and visiting the U.S. State Department, always brings us back to the private figure, in his undershirt as he prepares for bed, or talking to the faithful attendant who has served him since his days in Tibet. When he goes on tour, the Dalai Lama is often taken to labs and scientific conferences, and much more rarely to art galleries; his interest, one always feels, is in “investigation”—a favorite word—and in reality, not in the fanciful renditions we make of it or the daydreams we embroider around it. True to that impulse, Bauer offers what is, in effect, a documentary report of a life and not a romantic meditation on it, or wishful fairy tale; as he has said, he sees his book as essentially an archival one, making a record of the man’s movements while he is still among us, and keeping his own personality out of things so as to catch something unbiased (true to what seems a very unforced humility, the photographer’s own name appears in much smaller print on the cover of the book than that of his subject).

For many of us in the West, the part of the Dalai Lama’s life that is least apparent is, as it happens, the part that is most essential to his mission: his relations with his people, conducted far from the major networks, for the most part, and in a language few of us can understand. Although I have watched the Dalai Lama in action for more than thirty years now, I have seldom seen him just taking an audience with a fellow monk, or conferring in deepest private with his secretary of forty years, or dealing with a lame girl suddenly brought into his presence; in the flurry of our own projections and expectations and images of the man, it’s easy to lose sight of the elemental tremble and anticipation and respect that animates those thousands who stand along the road everywhere he goes, hands clasped in prayer as their ancestors’ hands were clasped. In many ways the book resembles one of those logs that newsmagazine photographers compile of presidential candidates waiting under tunnels, conferring with aides, and caught backstage on the campaign trail; the difference here is that the subject of this book is a man for whom backstage is the center of the action, and for whom power comes not from the crowd but in spite of it.

Journey for Peace includes a short text by the Swiss journalist Christian Schmidt describing a series of interviews conducted in many places with the Dalai Lama; though alert and undeluded, it is much more similar to what many of us may have read before (and besides, is not entirely accurate: the Dalai Lama’s mother didn’t bear sixteen children before her most celebrated son, but sixteen in all, and the Dalai Lama does not conduct a hundred interviews a year, but more like a hundred a month). Really, this is a book about what lies deeper than words, in a face, in a heart (with a rare capacity for making its concern, its goodwill or self-possession evident), and most of all in a soul embarked on its own mysterious journey. Pictures of crowds and bodyguards and swarming devotees give way, in this book, quite abruptly, to a picture of an empty chair.

As the Dalai Lama says, in the text here—and it could be the epigraph to the whole work—“From early morning until late at night, and even in our dreams, we experience all kinds of perceptions. We go from being relaxed to being anxious, we feel sometimes anger, sometimes desire, sometimes compassion. These are transitory states of mind that come and go, from moment to moment. But there must indeed be something that is aware of all this, a continuity of cognition that keeps on experiencing it even after we fall asleep. Yet that something is usually hidden to us, as if behind a curtain. So we need to remove that curtain.” It is a testament to the sincerity, the transparency, and the persistent sensitivity of Manuel Bauer’s eye that he begins to remove that curtain in this book, and so shares with all the rest of us something of the meaning of a man we often look at and rarely see.