In a traditional Zen monastery, the position of tenzo, or head cook, is held by a monk who is considered to “have way-seeking mind, or by senior disciples with an aspiration for enlightenment.” Here, Japanese Zen Master Dogen (1200-1253) instructs his monks on the importance of the position of the tenzo as it had been established in Regulations for Zen Monasteries, a Chinese collection of guidelines for monastic life written in the early twelfth century.

Zen monasteries have traditionally had six officers who are all Buddha’s disciples and all share buddha activities. Among them, the tenzo is responsible for preparing meals for the monks. Regulations for Zen Monasteries states, “In order to make reverential offerings to monks, there is a position called tenzo.”

Since ancient times this position has been held by accomplished monks who have way-seeking mind, or by senior disciples with an aspiration for enlightenment. This is so because the position requires wholehearted practice. Those without way-seeking mind will not have good results, in spite of their efforts…

The cycle of the tenzo’s work begins after the noon meal. First go to the director and assistant director to receive the ingredients for the next day’s morning and noon meals—rice, vegetables, and so on. After you have received these materials, take care of them as your own eyes. Zen Master Baoning Renyong said, “Protect the property of the monastery; it is your eyeball.” Respect the food as though it were for the emperor. Take the same care for all food, raw or cooked…

When you wash rice and prepare vegetables, you must do it with your own hands, and with your own eyes, making sincere effort. Do not be idle even for a moment. Do not be careful about one thing and careless about another. Do not give away your opportunity even if it is merely a drop in the ocean of merit; do not fail to place even a single particle of earth at the summit of the mountain of wholesome deeds.

Regulations for Zen Monasteries states, “If the six tastes are not suitable and if the food lacks the three virtues, the tenzo’s offering to the assembly is not complete.” Watch for sand when you examine the rice. Watch for rice when you throw away the sand. If you look carefully with your mind undistracted, naturally the three virtues will be fulfilled and the six tastes will be complete.

Xuefeng was once tenzo at the monastery of Dongshan Liangjie. One day when Xuefeng was washing rice, master Dongshan asked him, “Do you wash the sand away from the rice or the rice away from the sand?”

Xuefeng replied, “I wash both sand and rice away at the same time.”

“What will the assembly eat?” said Dongshan. Xuefeng covered the rice-washing bowl.

Dongshan said, “You will probably meet a true person some day.” This is how senior disciples with way-seeking mind practiced in olden times. How can we of later generations neglect this practice?…

Personally examine the rice and sand so that rice is not thrown away as sand. Regulations for Zen Monasteries states, “In preparing food, the tenzo should personally look at it to see that it is thoroughly clean.” Do not waste rice when pouring away the rice water. Since olden times a bag has been used to strain the rice water. When the proper amount of rice and water is put into an iron pot, guard it with attention so that rats do not touch it or people who are curious do not look in at it.

After you cook the vegetables for the morning meal, before preparing the rice and soup for the noon meal, assemble the rice buckets and other utensils, and make sure they are thoroughly clean. Put what is suited to a high place in a high place, and what belongs in a low place in a low place. Those things that are in a high place will be settled there; those that are suited to be in a low place will be settled there. Select chopsticks, spoons, and other utensils with equal care, examine them with sincerity, and handle them skillfully.

After that, work on the food for the next day’s meals. If you find any grain weevils in the rice, remove them. Pick out lentils, bran, sand, and pebbles carefully. While you are preparing the rice and vegetables in this way, your assistant should chant a sutra for the guardian spirit of the hearth.

When preparing the vegetables and the soup ingredients to be cooked, do not discuss the quantity or quality of these materials which have been obtained from the monastery officers; just prepare them with sincerity. Most of all you should avoid getting upset or complaining about the quantity of the food materials. You should practice in such a way that things come and abide in your mind, and your mind returns and abides in things, all through the day and night.

Organize the ingredients for the morning meal before midnight, and start cooking after midnight. After the morning meal, clean the pots for boiling rice and making soup for the next meal. As tenzo you should not be away from the sink when the rice for the noon meal is being washed. Watch closely with clear eyes; do not waste even one grain. Wash it in the proper way, put it in pots, make a fire, and boil it. An ancient master said, “When you boil rice, know that the water is your own life.” Put the boiled rice into bamboo baskets or wooden buckets, and then set them into trays. While the rice is boiling, cook the vegetables and soup. You should personally supervise the rice and soup being cooked. When you need utensils, ask the assistant, other helpers, or the oven attendant to get them. Recently in some large monasteries positions like the rice cook or soup cook have been created, but this should be the work of the tenzo. There was not a rice cook or a soup cook in olden days; the tenzo was completely responsible for all cooking.

When you prepare food, do not see with ordinary eyes and do not think with ordinary mind. Take up a blade of grass and construct a treasure king’s land; enter into a particle of dust and turn the great dharma wheel. Do not arouse disdainful mind when you prepare a broth of wild grasses; do not arouse joyful mind when you prepare a fine cream soup. Where there is no discrimination, how can there be distaste? Thus, do not be careless even when you work with poor materials, and sustain your efforts even when you have excellent materials. Never change your attitude according to the materials. If you do, it is like varying your truth when speaking with different people; then you are not a practitioner of the way.

If you encourage yourself with complete sincerity, you will want to exceed monks of old in wholeheartedness and ancient practitioners in thoroughness. The way for you to attain this is by trying to make a fine cream soup for three cents in the same way that monks of old could make a broth of wild grasses for that little. It is difficult because the present and olden times differ as greatly as the distance between heaven and earth; no one now can be compared with those of ancient times. However, if you practice thoroughly there will be a way to surpass them. If this is not yet clear to you it is because your thoughts run around like a wild horse and your feelings jump about like a monkey in the forest. When the monkey and horse step back and reflect upon themselves, freedom from all discrimination is realized naturally.

This is the way to turn things while being turned by things. Keep yourself harmonious and wholehearted in this way and do not lose one eye or two eyes. Taking up a green vegetable, turn it into a sixteen-foot golden body; take a sixteen-foot golden body and turn it into a green vegetable leaf. This is a miraculous transformation—a work of Buddha that benefits sentient beings.

When the food has been cooked, examine it, then carefully study the place where it should go and set it there. You should not miss even one activity from morning to evening. Each time the drum is hit or the bell struck, follow the assembly in the monastic schedule of morning zazen and evening practice instruction.

When you return to the kitchen, you should shut your eyes and count the number of monks who are present in the monks’ hall. Also count the number of monks who are in their own quarters, in the infirmary, in the aged monks’ quarters, in the entry hall, or out for the day, and then everyone else in the monastery. You must count them carefully. If you have the slightest question, ask the officers, the heads of the various halls or their assistants, or the head monk.

When this is settled, calculate the quantities of food you will need: for those who need one full serving of rice, plan for that much; for those who need half, plan for that much. In the same manner you can also plan for a serving of one-third, one-fourth, one-half, or two halves. In this way, serving a half portion to each of two people is the same as serving one average person. Or if you plan to serve nine-tenths of one portion, you should notice how much is not prepared; or if you keep nine-tenths, how much is prepared.

When the assembly eats even one grain of rice from Luling, they will feel the monk Guishan in the tenzo, and when the tenzo serves a grain of this delicious rice, he will see Guishan’s water buffalo in the heart of the assembly. The water buffalo swallows Guishan, and Guishan herds the water buffalo.

Have you measured correctly or not? Have the others you consulted counted correctly or not? You should review this closely and clarify it, directing the kitchen according to the situation. This kind of practice—effort after effort, day after day—should never be neglected.

When a donor visits the monastery and makes a contribution for the noon meal, discuss this donation with the other officers. This is the traditional way of Zen monasteries. In the same manner, you should discuss how to share all offerings. Do not assume another person’s functions or neglect your own duties.

When you have cooked the noon meal or morning meal according to the regulations, put the food on trays, put on your kashaya [a patched robe worn over one shoulder], spread your bowing cloth, face the direction of the monks’ hall, offer incense, and do nine full bows. When the bows are completed, begin sending out the food.

Prepare the meals day and night in this way without wasting time. If there is sincerity in your cooking and associated activities, whatever you do will be an act of nourishing the sacred body. This is also the way of ease and joy for the great assembly.

Although we have been studying Buddha’s teaching in Japan for a long time, no one has yet recorded or taught about the regulations for preparing food for the monks’ community, not to mention the nine bows facing the monks’ hall, which people in this country have not even dreamed of. People in our country regard the cooking in monasteries as no more developed than the manners of animals and birds. If this were so it would be quite regrettable. How can this be?

Taking up a green vegetable, turn it into a sixteen-foot golden body; take a sixteen-foot golden body and turn it into a green vegetable leaf. This is a miraculous transformation—a work of Buddha that benefits sentient beings.

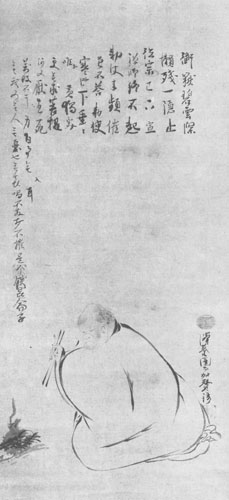

In the fifth month of the sixteenth year of Jiading [1223], I was staying on a ship at Qingyuan. One time while I was talking with the captain, a monk about sixty years old came on board. He talked to a Japanese merchant and then bought some mushrooms from Japan. I invited him to have tea and asked where he came from. He was the tenzo of Mt. Ayuwang.

“I am from Shu in western China,” he said, “and have been away from my native place for forty years. Now I am sixty-one years old. I have visited monasteries in various places. Some years ago, priest Daoquan became abbot of Guyun Temple at Mt. Ayuwang, so I went to Mt. Ayuwang and entered the community and have been there ever since. Last year when the summer practice period was over, I was appointed tenzo of the monastery. Tomorrow is the fifth day of the fifth month, but I have nothing good to offer the community. I wanted to make a noodle soup, but we did not have mushrooms, so I made a special trip here to get some mushrooms to offer to the monks from the ten directions. ”

I asked him, “When did you leave there?”

“After the noon meal.”

“How far is Mt. Ayuwang?”

“Thirty-four or thirty-five Ii [about twelve miles].”

“When are you going back to your monastery?”

“I will go back as soon as I have bought mushrooms.” I said, “Today we met unexpectedly and had a conversation on this ship. Is it not a good causal relationship? Please let me offer you a meal, Reverend Tenzo.”

“It is not possible. If I don’t oversee tomorrow’s offering, it will not be good.”

“Is there not someone else in the monastery who understands cooking? Even if one tenzo is missing, will something be lacking?”

“I have taken this position in my oId age. This is the fulfillment of many years of practice. How can I delegate my responsibility to others? Besides, I did not ask for permission to stay out.”

I again asked the tenzo, “Honorable Tenzo, why don’t you concentrate on zazen practice and on the study of the ancient masters’ words rather than troubling yourself by holding the position of tenzo and just working? Is there anything good about it?”

The tenzo laughed a lot and replied, “Good man from a foreign country, you do not yet understand practice or know the meaning of the words of ancient masters.”

Hearing him respond this way, I suddenly felt ashamed and surprised, so I asked him, “What are words? What is practice?”

The tenzo said, “If you penetrate this question, how can you fail to become a person of understanding?”

But I did not understand. Then the tenzo said, “If you do not understand this, please come and see me at Mt. Ayuwang some time. We will discuss the meaning of words.” He spoke in this way, and then he stood up and said, “The sun will soon be down. I must hurry.” And he left.

A refined cream soup is not necessarily better than a broth of wild grasses. When you gather and prepare wild grasses, make it equal to a fine cream soup with your true mind, sincere mind, and pure mind. This is because when you serve the assembly—the undefiled ocean of buddha-dharma—you do not notice the taste of fine cream or the taste of wild grasses. The great ocean has only one taste. How much more so when you bring forth the buds of the way and nourish the sacred body. Fine cream and wild grasses are equal and not two. There is an ancient saying that monks’ mouths are like a furnace. You should be aware of this. Know that even wild grasses can nourish the sacred body and bring forth the buds of the way. Do not regard them as low or take this lightly. A guiding master of humans and devas should be able to benefit others with wild grasses.

Again, do not consider the merits or faults of the monks in the community, and do not consider whether they are old or young. If you cannot even know what categories you fall into, how can you know about others? If you judge others from your own limited point of view, how can you avoid being mistaken? Although the seniors and those who came after differ in appearance, all members of the community are equal. Furthermore, those who had shortcomings yesterday can act correctly today. Who can know what is sacred and what is ordinary? Regulations for Zen Monasteries states, “A monk whether ordinary or sacred can pass freely through the ten directions.”

If you have the spirit of “not dwelling in the realm of right and wrong,” how can this not be the practice of directly entering unsurpassable wisdom? However, if you do not have this spirit, you will miss it even though you are facing it. The bones-and-marrow of the ancient masters is to be found in this kind of effort. The monks who will hold the position of tenzo in the future can attain the bones-and-marrow only by making such an effort. How can the rules of reverend ancestor Baizhang be in vain?

After I came back to Japan I stayed for a few years at Kennin Monastery, where they had the tenzo’s position but did not understand its meaning. Although they used the name tenzo, those who held the position did not have the proper spirit. They did not even know that this is a buddha’s practice, so how could they endeavor in the way? Indeed it is a pity that they have not met a real master and are passing time in vain, violating the practice of the way. When I saw the monk who held the tenzo’s position in Kennin Monastery, he did not personally manage all of the preparations for the morning and noon meals. He used an ignorant, insensitive servant, and he had him do everything—both the important and the unimportant tasks. He never checked whether the servant’s work was done correctly or not, as though it would be shameful or inappropriate to do so—like watching a woman living next door. He stayed in his own room, where he would lie down, chat, read sutras, or chant. For days and months he did not come close to a pan, buy cooking equipment, or think about menus. How could he have known that these are buddha activities? Furthermore, he would not even have dreamed of nine bows before sending the meals out. When it comes time to train a young monk, he still will not know anything. How regrettable it is that he is a man without way-seeking mind and that he has not met someone who has the virtue of the way. It is just like returning empty-handed after entering a treasure mountain or coming back unadorned after reaching the ocean of jewels.

Even if you have not aroused the thought of enlightenment, if you have seen a person manifesting original self you can still practice and attain the way. Or if you have not seen a person manifesting original self, but have deeply aroused the aspiration for enlightenment, you can be one with the way. If you lack both of these, how can you receive even the slightest benefit?

When you see those who hold positions as officers and staff in the monasteries of Great Song China, although they serve for a one-year term, each of them abides by three guidelines, practicing these in every moment, following them at every opportunity: (1) Benefit others—this simultaneously benefits yourself; (2) Contribute to the growth and elevation of the monastery; (3) Emulate masters of old, following and respecting their excellent examples.

You should understand that there are foolish people who do not take care of themselves because they do not take care of others, and there are wise people who care for others just as they care for themselves.

A teacher of old said:

Two-thirds of your life has passed,

not polishing even a spot of your source of

sacredness.

You devour your life, your days are busy with this

and that.

If you don’t turn around at my shout, what can I do?

You should know that if you have not met a true master, you will be swept away by human desire. What a pity! It is like the foolish son of the wealthy man who carries a treasure from his father’s house and discards it like dung. You should not waste your time as that man did…

If anything should be revered, it is enlightenment. If any time should be honored, it is the time of enlightenment. When you long for enlightenment and follow the way, even taking sand and offering it to Buddha is beneficial; drawing a figure of Buddha and paying homage also has an effect. How much more so to be in the position of tenzo. If you act in harmony with the minds and actions of our ancient predecessors, how can you fail to bring forth their virtue and practice?

♦

Excerpted from Moon in a Dewdrop: Writings of Zen Master Dogen (North Point Press), edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi. This passage was translated by Arnold Kotler and Kazuaki Tanahashi.