A Himalayan Journey

By David Crow

Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 2000

370 pp.; $24.95

Books on Asian medicine easily fall prey to the Exotic East problem, causing them too often to resemble those blissful magazine spreads on places like Timphur or Lahore: the details are extraordinary, but suspect in their perfection. With skill and unclouded vision, David Crow does not romanticize the complexities out of his subject, which is what makes In Search of the Medicine Buddha such an invaluable book for anyone interested in Eastern medicine.

In Search of the Medicine Buddha, an exuberant account of his ten-year period of apprenticeships with Tibetan doctors, alchemists, and Ayurvedic teachers in Kathmandu, leaves nothing out. Right off, he charges head on into questions that other Western pilgrims have wondered about, but may not have had the nerve to ask “Why are goddesses worshipped in every temple [in Nepal and Tibet], but women treated as inferior incarnations?’ .. Why are the [medical] traditions … suppressed by their own culture, even as they are beginning to be embraced by the modern world?” And: If these spiritually based healing systems are so good, why are the practitioners so often sick?

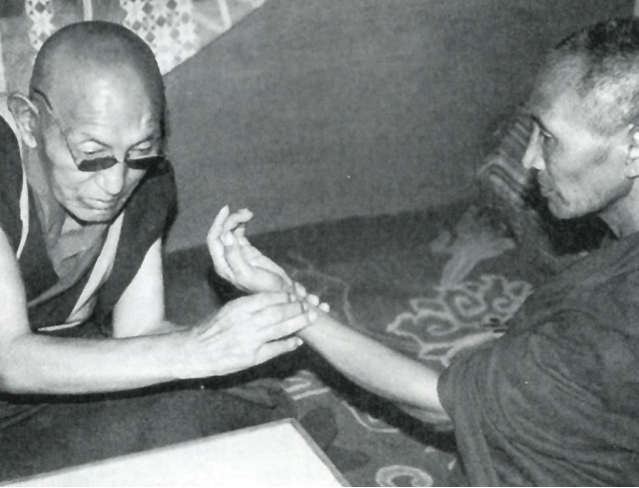

Crow came to Kathmandu in 1987, with some training in herbology and acupuncture, and soon after became a pupil of Ngawang Chopel, a Tibetan doctor and lama who’d spent several decades imprisoned by the Chinese. Chopel spoke no English, Crow no Tibetan, but aided by mutual interest and a translator, they cracked the language barrier.

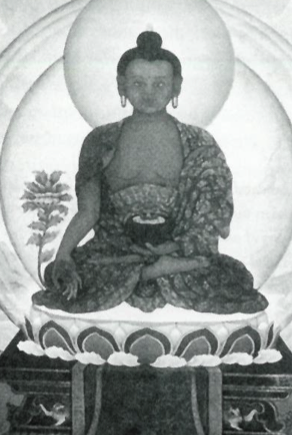

In the first few chapters, he delivers up an incisive view of Tibetan medicine. In the physical realm, doctors examine patients’ tongues and pulses, prescribing herb and mineral pills to counteract disturbances of the three humors (air, wind, and fire). But there’s a much stronger spiritual component, centering on invocation of the deep-blue Medicine Buddha who sits in lotus pose, left hand cupping a bowl of nectar, right hand holding the powerful myrobalan plant, “omniscient mind coursing through the deep ocean of compassion,” he writes.

Tibetan medicine’s pageantry (probably a boost to healing) has been written about before: Rays of light stream from the Buddha’s third eye, his throne is composed of talking jewels. But Crow’s account of the elaborate Medicine Buddha invocation is superb and rare in the literature. Practitioners, doctors and patients both, become the deity mentally before dissolving him into their bodies. “This method of disassociating from ordinary perceptions,” he writes, of “entering into emptiness, appearing as a deity, then returning through emptiness to the physical body, teaches the grasping mind to liberate itself from habitual clinging to perishable outward appearances.”

The narrative is looping and can be a little disorienting. Crow makes sudden jumps from Tibetan to Ayurvedic medicine (not a wild leap, however, as the first borrowed heavily from the second), darts down side pathways to investigate alchemy and Chinese herbal medicine. Scenes from his various apprenticeships flicker past. There’s the moody Ayurvedic practitioner who hangs a sign advertising “Sex Change”—prenatal, that is, by means, he claims, of a specialty concoction of herbs. There’s the young Gopal, whose businessman father takes a dark view of his desire to minister to the poor. “I am a dharma man,” Gopal declares. There’s the pounding, brooding landlord Bernard, who worships a snake, or naga, in his backyard.

Throughout the narrative, ideas fly. Lamenting the sludgy, polluted state of Kathmandu, Crow writes, “As plants disappear, our ability to make medicines, whether as botanical preparations or refined pharmaceuticals, also vanishes.”

“Let’s live a symbiotic not an antibiotic life,” one of his characters cries.

By book’s end, he’s circled back to the hard questions he’d first proposed. Why are so many Tibetan medical practitioners sick, for instance? “Spiritual teachers are human beings,” Dr. Chopel says, an idea that, applied to their own medical system, might floor some Western patients. “Even though they may have eradicated the root of karma from their mindstream, thus closing the door to future suffering, the body is still subject to decay and death.

“They manifest illness and death to purify the last of their karma,” he adds.

Human doctors! Plants, not penicillin! But if many aspects of Eastern medicine are appealing, one isn’t: the widespread use of mercury—understood in the West to be a deadly poison—in medical treatments. Crow tackles this straight on, but finds himself in a bind. He offers the explanations his teachers have given him: Preparation methods are different and safer there; so are the amounts and compounds used. But he adds, “If charges of toxicity [with mercury when prescribed by an Ayurvedic or Tibetan doctor] are to be made, they should be proved.” Guilty until proven otherwise is clearly the more prudent course; this is the one place where Crow goes fuzzy.

Otherwise, he has the clear eye of a journalist. He refuses to crop the shots. Even as he delivers tantalizing details of Tibetan and Ayurvedic medical practice, he interposes distressing scenes of contemporary Kathmandu: “the waters are fouled with turbid waste… [it’s] a place of asphyxiating pollution, miserable overcrowding and cultural decay.”

We get the picture. And by not looking away, we get a smidgen of the deep wisdom he’s accumulated through his journeys. By the time he writes, “The healing of humanity’s ancient wounds and the rebirth of Dharmic culture rests upon ecological renewal,” it doesn’t read like one more eco-exhortation. It reads like absolute fact.