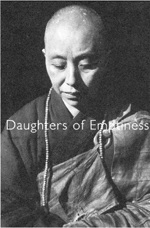

Buddhist culture in China is a story langely told by men, for men, and about men. Echoes occasionally emerge suggesting that women, too, made rich contributions, but how many names come to mind? In Daughters of Emptiness: Poems by Buddhist Nuns of China (Wisdom Publications, 2003, $16.95 paper), Beata Grant retrieves not only the namesbut also a striking selection of poems by forty-eight Buddhist women, from the fifth century to the early twentieth.

many names come to mind? In Daughters of Emptiness: Poems by Buddhist Nuns of China (Wisdom Publications, 2003, $16.95 paper), Beata Grant retrieves not only the namesbut also a striking selection of poems by forty-eight Buddhist women, from the fifth century to the early twentieth.

Grant—chair of the Department of Asian and Near Eastern Languages and Literatures at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri—must have gone on a considerable search to locate even this modest gathering of poems. In a note on Haiyin—a poet she places at the end of the T’ang dynasty—Grant observes that the imperial anthology of T’ang dynasty verse, which preserves more than fifty thousand poems by some two thousand poets, includes only a single example by a Buddhist nun. One nearly weeps at the thought of such omission during the three centuries in Chinese history when poetry flourished as it has at no other time, nowhere else on the planet, and Buddhism set its indelible mark on East Asia.

Accounts of the earliest nuns remains sketchy. Many have no dates, their work surviving with only a bit of provocative hearsay attached to their names. But as Daughters of Emptiness draws closer to our own era, more material comes to light. The women sound sober, resolute, like Jingming, abbess of Xiaoyi convent in Hangzhou, who writes: “Outside the gates are the river’s waters,/Which reflect both the face and the mind./The face of truth doesn’t worry about wrinkles,/As long as the mind of the Way is profound.” And who can ignore the words of Lianghai of Suzhou, giving her disciples stalwart encouragement: “The awesome and peerless attainment of buddhamind is not weakened because of the presence of nuns.” In one poem she strikes a note that remarkably prefigures William Blake: “In a single grain of sand is stored the entire world.”