Mayordomo: Chronicle of an Acequia in Northern New Mexico

Stanley Crawford

University of New Mexico Press, 1993

243 pp., $18.95 paper

Far Tortuga

Peter Matthiessen

Vintage Books, 1988

416 pp., $16.95 paper

In a time of water emergencies everywhere every week, of giant floods, continental drought, images virtually statistical of the Pacific Ocean circulating plastic in a tightly cohesive looping swath thousands of miles long, where do we turn to get a grasp of the crisis? It’s a maze, an unrelenting moment of parched forests where animals and plants are surprised to be newly extinct and men fish all night for what’s left; great rivers ambitiously dammed, but unwisely, we now see; and our own Colorado exhausting its waters as they run down to the Gulf, yielding less and less of a contracted share to states they pass through, the farmers besieged by West Coast cities thirsting for their water rights. To say nothing of this polemically, bewilderingly technical time of a Supreme Court ruling that a “creek” full of lead, zinc, and oil in Alabama is not covered by the Clean Water law. So perhaps to refresh my thought, if not to save the day, I find myself turning to small-scale comings and goings.

Two American books of the last generation with apparently little in common but water still speak to me and, in the strange neighborhood of my mind, to each other— Peter Matthiessen’s Far Tortuga (1975) and Stanley Crawford’sMayordomo (1988): one, a novel about a boat hunting the great green turtles, what’s left of them, in the Caribbean fishery—farming the sea, we like to say; the other, a nonfiction account of a small irrigation ditch fed from a river in a northern New Mexico valley, a one-year chronicle of this acequia, which anciently means both the channel and the association of members who share it and maintain it.

“Small-scale” seems hardly Matthiessen, best-selling seafarer, Himalayan trekker, naturalist, and anthropologist; yet sea, sky, and lives draw in upon this Cayman Islands schooner like the close-ups of oil slicks, an oar blade grating against “dead coral,” “slops [dumped] into … clear water [so] the stain rolls.” And nearer still are the voices we come to know aboard this 59-foot sail- and diesel-powered vessel, Lillias Eden, in dangerously poor repair and with a dubious crew (“goin to sea!”): poor blacks, from the irascible, driven Captain Raib Avers, prowling the deck, a skilled harpooner holding stubbornly with experience and control, to the eight or nine others, the strong one, Byrum, in clean khakis working, and the weaker, garrulous, raffish, drunk, ranting, threatening men passing the time on the way to the turtling grounds, reflecting on a supposedly better time and on seamanship, sex, impoverished and dispersed families, estranged fathers and sons, this job—the knowledge of the waters, what lies beneath them, the turtles grazing while the light is right, their epic eyesight, the eight-hundred-pounders you don’t see anymore, navigation better than a bird’s. Also, the famous turtlers of the “backtime.” Also, the reading of dreams, the gross pathos of “anything black, dat is bad luck” and “Green things … or silver money or colored folks”; but to dream “about a white person” is good luck, “white clear water”—but if, while putting out the nets, “you don’t feel no sign in your hand,” you next day will “find a water set, cause dey nothing in dose nets but water.”

Things later falling apart. And for all the mess and rot, the roaming, the catch and butchering cruelty, overloaded immigrant boats passing across this desert of water, famished pirates, the destitute beyond hope of a share—a share of what? Still, it is an inward elegy of composition, even of ravishing beauty, its impressions arresting, a meditation.

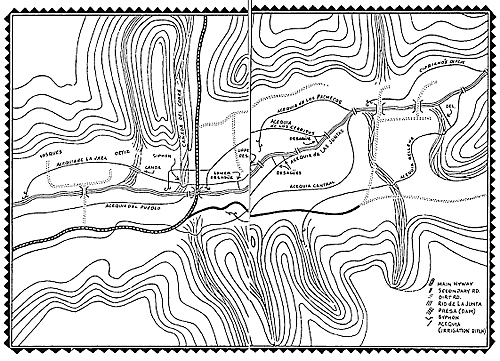

Also about a traditional relationship to water, Stanley Crawford’s Mayordomo, with its method, core, and social persistence stands in unassuming but significant contrast to Far Tortuga. Mayordomo became Crawford’s title when he was elected by the acequia in March of 1985 for a term as manager of the irrigation ditch; later it became his title for his book about being mayordomo. An educated Anglo in a mainly Hispanic working-class community, his job to hire the crew of below-minimumwage ditchdiggers, schoolkids, seventyyear- olds—thirty-strong the first day, thirteen missing the second. The annual, messy tasks of clearing the watercourse section by section will prove yearlong and endless work: cutting back willows, building up banks, digging out constricting grass, “sandbars to shovel out on the inside of bends … to keep the [serpentine] ditch wide and deep enough to accept the rolling tongue of water, clogged with leaves and twigs, muddy and white foamed, that will race down the three- or four-foot-wide channel” when the gates are opened.

Crawford is always on call to attend to the small emergencies. Delays in getting “a backhoe down from a village ten miles up the mountain” after a flood that “threw up a roll of gravel and rocks into the mouth of the ditch,” repairing a small dam “which everyone here (except myself) has done … since the time they were kids,” cutting up limbs of a “cottonwood rotten at the base” that “has fallen conveniently over the mouth of the ditch.” Through the year, water is present “like some creature” and is everywhere in Crawford’s book, yet elusive, passive in its power to be subordinate to other things if it ever had any inherent power. Crawford finds himself growing to be part of the ditch—he will not work a small crew “half to death to prove something … that this is work or that I am in charge. The ditch itself will pace our labors.” Clearing the channel is clearing the water; an aesthetic seems to surface, of tight work with others and water use.

The ditch unfolds again and again, three miles of it, place by place. “A mayordomo has to deal with people whole, often angry … regarding a commonplace substance that can inspire passion like no other …” A heavy from another acequia who may give you water if you need it but not as your right. Violent dialogue. Silent dialogue, “the eyes of [a very young crew member telling me] I am a newcomer upstart here” (not true, Crawford’s been here longer than he has). Internal dialogue of this mayordomo man who likes to talk and likes silence, acknowledges “two schools of thought,” putting a lot of water into the ditch the first two days of the season or only a little; rejecting wryly, stubbornly both options in favor of a medium amount.

In turn, two sides of Crawford, who, sometimes “the only gringo on the crew,” rediscovers through his acequia water relationships seasons of his own personal year: summers, working with his Hispanic neighbors outside; winters, spending time with Anglos inside. And writing, which he has earned. Remembering Kafka’s “The Burrow” as he reflects on often destructive animals, interfering yet perverse partners: a muskrat staring him in the face, maybe pretending not to know what he is; dambuilding beavers with legendary teeth if you think of reaching into a mass of branches to unclog the ditch. Crawford, right here where he lives, hears like his own voice one night when it rains, “the skies … saying that as soon as we all managed to cooperate among ourselves … there would be enough water for everyone.”

From the sky comes the water it is said we have a natural right to, wherever it has cycled up or down from, the sea, mountain snowmelt. That grandeur, not of special interest to Crawford, lurks like faith in the dimensions of Matthiessen’s voice. At dawn “stars fail” above the Eden as she beats across a channel, “the sky filled with pale light” watched by the men, a “rim of fire … where the corona clings to the horizon”; and so often to the squeak and bang of the hull straining, and “wind and waves … lost” on the reef, and “no time, no space, but only the chaotic rush of the dark universe” that to glimpse the men of this crew described once in a great while (though on an early page the ship’s manifest listing them all with information printed out feels more like dramatis personae) is to be reminded that their vivid, though also strange presence so convincing after the early pages is created mainly through dialogue. Across the “bleak ocean” it’s the voices of the men talking that most strike the reader. If we pay attention we know who speaks, but the talk is almost never ascribed. The mens’ faceless voices persist, continuous as the Caribbean waters, distinct and fresh.

This is Matthiessen’s most effective fiction because of the strangely prevailing dialogue, the concrete abstraction of these voices, the scattering gaps into which we are drawn somewhere between its effect and a physically fully framed scene which Matthiessen mostly does not do. The voices pointed as can be, yet adrift and free as a force and also, fluid and solvent like water, their smallness in the history they tell and its decline. The scary, unpredictable moment- by-moment dismembering of the voyage, while the snatches of dialogue go on, like closeness, eddying sounds, joke, lament (“ain’t people any more”), dialect, hunger, beauty for these men, weather, “de wind in de reefs,” a wide sea that breeds, while against its unknowing (“Green turtle very mysterious, mon”) we have its offhand survivors casually slitting the white throat of the great animal that blinks (“best cotch turtles one time in dis life just so you know it”), burning holes into flippers with a poker—“ a quick sweet stink of flesh” so they can be “lashed tight across the belly,” though some of these turtles are dumped helpless overboard for some other special enemy, who “bite de head off” but “give up den and go way … cause dat turtle head is still openin and closin inside of de shark, de way de turtle do when you chop his head off.”

And what exactly is this great turtling tradition we’re told of now to be curtailed (in the early 1970s) by new “Spanish” regulations, the best of the fisheries soon to be off limits to Cayman boats? It is a siltclogged estuary delta near the Nicaragua Honduras border along the Miskita Coast where Raib in search of the customs post upriver to register and be legal tries to take a catboat in with the tide falling, deep mud grounding them. Raib rails against bad boat-making and the river, but he has no reason to be angry at nature, Stanley Crawford recalls: anger comes only from dealings with other men.

No two coasts are equal, even fractal measurements prove that now. Yet all adventures are equal. Confronted with the prospect of radical change, Crawford thinks his way through the meanings of the promised new State adjudication of acequia water rights. Traditionally a share entitles a parciante to take water from the ditch a certain number of hours a week, the amount of water available to the acequia from the river, a variable given the year and other realities. Water and land go together under the old Spanish law, and a parciante could not transfer or sell one separately from the other. Under adjudication a share of this obviously variable amount of water would become a fixed share measured in acre feet of a whole regional system, in fact a commodity that can be rented or leased in a huge market unrelated to the acequia it was attached to. What was held in common by oral agreements can now be held privately. A parciante without water rights is no longer a parciante. In effect, adjudication, clearer than the old, sometimes “myopic” law based on common sense, would destroy the civic institution of the acequia unique in its democratic autonomy. These alternatives aren’t that simple, Crawford figures. But for him, having “worked to become a neighbor,” the thousand acequias in New Mexico make a “web of almost microscopic strands and filaments that have held a culture and a landscape in place for hundreds of years.” His thought will take him further still, and, companioning it, usher in a climactic, perhaps surprising, de-emphasis to come.

It meets us everywhere these last couple of decades, and we it more than halfway. “Water brings the distant near”—“Water’s a personal thing”—“What does water look like?” observes the New York visual artist, Roni Horn, among the upward of five or six hundred numbered “footnotes” that in, it seems, deliberately hard-to-read small print line the lower margins of fifteen magnificent and disturbing photographs of water hanging in one room of her recent show at the Whitney Museum. Water like mountains seen from above. Textured like lava. Or all fluid surface seductively close, or camouflaged reflections—their anonymous planes threateningly leaden and coldly immediate. Polluted with metaphor, too, for “Water is the master verb: an act of perpetual relation,” the insights (“Water is sexy”) go on and on, rich yet self-indulgent, often leaving out what might responsibly follow from a putative idea as in fact Horn inserts each footnote number codelike and nearly invisible into the photo above as if keying the footnote to explain the corresponding wave, ripple, fold, trough, dot or turn of light. Water, all there, palpable, potent— yet the artist has to tell us in subtitles and often in footnotes that it’s the Thames. Is it some cachet or rescue words have for this visual artist? To redeem the water from its unsustainable silence, repeatedly in fact telling us what a magnet the Thames is for suicides, “a self-entrance to simply not being here.”

So that while I ponder her amplifying words against what Matthiessen leaves out in order to sustain his own beautifully alone voices, I’m reminded by the visual artist’s death theme of the novelist’s epigraph: “Death, Thou comest When I had Thee least in mind,” from the fifteenth-century play Everyman.

It is a secular death of Nature we are bringing about, and the art of Far Tortuga shows both large-scale and humanly smallscale catastrophe whether it says Yes or No. Darkly, shiningly, heartbreakingly—and in lyrical resignation which is, thus, just short of thinking through more fully what has gone wrong, what we are looking at.

A small-boat subsistence sometimes. Almost a living. “I no farmer,” says Captain Raib’s engineer, proud, rootless, with a liking for the violence of “soldierin” in Colombia. Another crewmember has fond memories of some land and a cow in the Bay Islands, “Have your own ground.” Another, “I know practically everything dat grows, cause I were reared up in de island, and by dat I come to know things.”

We can know about most things if we are committed to knowing. Curious that Stanley Crawford finds not only that acequias, these half man-made, half natural “features of the landscape,” are structures of considerable beauty, but that the aesthetic aspects of farming are as important to him as the utilitarian ones. Writing in the mid- 1980s, when few members of his acequia make their living by farming, Crawford finds water’s real value in “keeping our communities together …”; to this, “even agricultural use may be secondary.” Thus, perhaps he has arrived at his partly aesthetic view of water through his valuing of community and of people.

What can this seriously matter at a time of material emergency around the Earth? An answer can be found in E. F. Schumacher’s Small Is Beautiful (1973), the early chapter “Buddhist Economics.”

Coming off County Route 48 at Mattituck Inlet, Long Island, driving or walking, you might hardly notice beyond the parking lot and off to the left of the boat ramp a new swale of grasses sloping down to the water: drought- and flood-tolerant Switchgrass; hardy wetland Marsh Mallow; Turtlehead, which attracts butterflies; and Little Bluestem grasses grown locally. These and other plants, including the dominant phragmites that require managing, form a newly graded buffer zone to take the overflow of toxic stormwater runoff with its salts and petroleum products from the highway and in effect clean it—of its nitrogen, phosphorus, and fecal coliform bacteria— before it enters the inlet, where the pollution had long threatened wildlife and shellfish. The intervening parking lot itself has been repaved with a permeable surface of recycled glass. This and a bluestone substrate take most of the runoff but far from all.

Interpretive signs near the water’s edge identify flora, birds, aspects of the design. I’m lucky enough to hear it from the person largely responsible for the WATERWASH project, Lillian Ball, an environmental artist who has been working with water for thirty years. A sculptor, botanist, photographer, a deeply knowledgeable spirit who worked hard to interest local government in backing the project, she has shaped a whole place that speaks in collaboration with her and with us. She raised the public money principally from the Long Island Sound Futures Fund, designed the project herself, and brought in contractors and helpers, many of them young students.

I visited the WATERWASH “opening” in early November 2009. Not a gallery. Much more. There’s an osprey nest and a mating couple now, mallards, egrets, and black-backed gulls again. Are the monitoring stations established in this saltwater inlet by the Department of Environmental Conservation recording lower pollution levels? It’s too early to know.

Is this our life? An example of coherence, economy, self-sustaining improvisation as life? If so, in some rough and changing manifold is it beautiful? As a complicated, hardly independent event made in ways that would educate and sustain and surprise us—if we look, is it beautiful?

The author of nine novels and a forthcoming volume of short fiction, Night Soul and Other Stories, Joseph McElroy is completing a non-fiction book about water. He lives in New York City.