Issan Tommy Dorsey, born in 1933, grew up on the West Coast, dropped out of college, and joined the Navy. During the Korean War, he was discharged for homosexuality. Back home, after trying a few “straight” jobs, Dorsey eventually found work in a nightclub as a waiter, a host, and finally as a performer in the drag revue. He spent years running the streets as a drug-addicted, alcoholic female impersonator and prostitute. Back in San Francisco in the sixties, Dorsey received his first instruction in meditation from Shunryu Suzuki Roshi. After that encounter, Dorsey practiced with such steadiness that his teacher named him” one mountain,” Is-san. Two decades later, Dorsey became a Zen master himself, acting as abbot of One Mountain Temple, also known as Hartford Street Zen Center in San Francisco. Living in the midst of an epidemic, he began to bring homeless people with AIDS into the temple to care for them. This eventually blossomed into MAITRI hospice, located in the building next to the temple. Issan himself died from AIDS in 1990. The following excerpts are from Street Zen: The Life and Work of Issan Dorsey, by Tensho David Schneider, published by Shambhala Publications.

———————————————————————————————————————

WHATEVER BAD HABITS Tommy Dorsey had, the creature with the stage name Tommy Dee had worse. By changing his name, Tommy slipped the last and most binding loop of authority, his family. Tommy Dee came from nowhere, answered to no one. Unmoored, he had permission to go in any direction, and he went for more drugs. His habit, he said,

. . . got bigger as I was performing at Ann’s 440. I started shooting more and more heroin all the time. I got strung out. If I didn’t have my taste, I’d be sick.

At one point, I moved in a man who was Lenny Bruce’s pusher, a black man named Jimmy. I moved him in with me, and I had all the heroin I wanted. He one day told me that it was costing us $75 a day for my habit. That means before we would sell it. In other words, I developed a pretty big burner, because I could get it.

When I wasn’t with Jimmy, I hung around with a couple of lesbians. This black girl used to go out and turn tricks, and the white girl and I used to go out and sell heroin down at this after-hours place on the wharf, so we could have some to shoot. . . . After a while I just pretty much knew how to do it. Get it here, sell it there, be in the right place at the right time.

Along with heroin, Tommy got to know addiction’s sibling—prostitution:

. . . it came with the job. People would expect it. Men would come with their wives one night, then the next night they’d come alone. . . people who would be interested in a man in drag. Sometimes too, I would dress as a butch young guy, and sometimes I’d go out in drag, depending on what they wanted. I think Ann [Ann Dee, co-owner of Ann’s 440J actually pimped me-it’s a little vague. She told me to go looking straight, not to be dressed up.

But I can remember turning tricks with Desiree, a lesbian and a prostitute who used to be one of George Raft’s girls. He was a well-known mobster type. Desiree was beautiful—a white girl who was blond and hung around at Ann’s. She and I used to go turn tricks together.

We’d go out with a married couple, let’s say. We meet them at their motel and have cocktails. I’d be in drag and she’d be in her clothes. Then we’d go to bed with them, the husband and the wife. We’d get our money and go out and shoot it all.

Throughout this period Tommy relished the low life. He seemed so pleased and so much at ease that companions had trouble censuring him, even if they were so inclined. Reggie Mason, who performed with Tommy for years, said:

I feel that all the things we’ve sort of kidded and laughed about in his behavior, being a hooker and a this and a that—they sound so foul about someone else you might know. But I don’t find them that way with him. . . . It was a very natural thing for him to do. But I don’t ever recall his instigating it. It was that other people would come to him and say, Hey, I’ve got a boyfriend out there, or a couple, or whatever, and you can get twenty-five bucks or whatever he would get, if you want to join us. . . . He sort of went along with anything, but he never particularly instigated any of it.

Whatever his personal reactions were to successfully negotiating a dark, dangerous world, Tommy had other reasons to count this as a happy time. He’d finally become an entertainer; he may have been only a small fish in a big pond, but the pond was famous, richly stocked with talent, and he was glad to be swimming there.

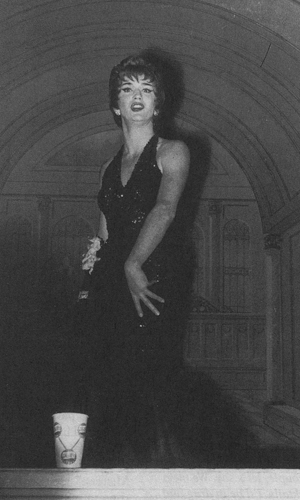

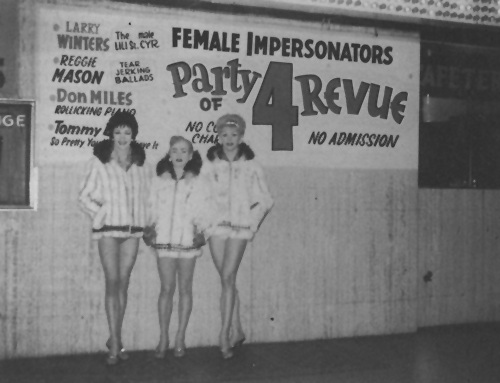

Tommy himself never qualified as a singer, though he keenly appreciated musical ability in others. He had a rough, low voice, and not much aptitude for carrying a tune. In his entire career as an impersonator, Tommy seems to have sung just a few songs, primarily “Hard-Hearted Hannah,” and “Steam Heat”—and those only after he emerged from the chorus of the act Ann Dee produced, called “Larry Winters and the Four Lovely Misters.” He could, however, trot around the stage in time to music, and whatever it was he actually did, he did with pride:

We had a much better show than Finnochio’s [another drag club]—because Ann saw to it. I mean it was really good. She had us out there in show-girl opera hose and feathers, marching around and tap-dancing on boxes, a live band up on the side, up high. Good musicians, always.

Related: A Big Gay History of Same-sex Marriage in the Sangha

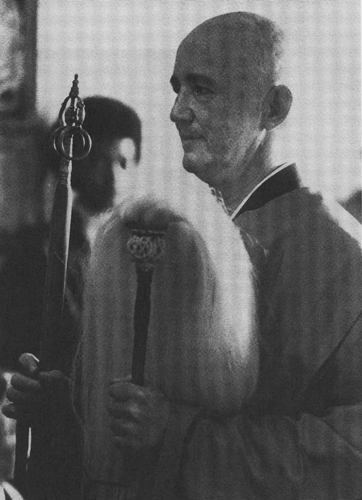

SHUNRYU SUZUKI ROSHI now shuttled between his Japanese congregation at Sokoji temple in Japantown, his Page Street City Center, and several satellite sitting groups around the Bay Area—most notably in Berkeley and Palo Alto. But when practice periods happened at Tassajara, which they did twice a year, Suzuki Roshi spent a good deal of time there. For this reason, and because of the sheer challenge of life there, Tommy went back in 1970, having first done a practice period in the fall of 1969. He returned in the summer, when non-Zen students—paying guests—filled Tassajara’s cabins, enjoyed the hot springs, and ate well-made vegetarian meals. Even though he’d drawn inspiration from Suzuki Roshi all along, Tommy suddenly became more conscious of his teacher’s power:

I didn’t really see who he was before. He came back to Tassajara part of that summer, and gave lectures. I was working in the office, and I used to come and look through the side window at him up there giving lectures. I’d peek at him. That’s when I can remember saying to myself, “Oh my god! Who is this man?” I saw him before, but I didn’t know it, and now it started coming through: “Oh my goodness. This man is far out.”

When the weather turned and the practice period began, Tommy stayed on. His feeling for Suzuki Roshi continued to deepen. As anyone who has fallen in love knows, the most mundane moments can pack a tremendous inexplicable wallop:

I was sick for six weeks during the next practice period. Suzuki Roshi was visiting, and he used to come from the baths at the same time every day. One day I looked out the window and I saw him. So then every day I knew what time, I’d look out my window at him. It just thrilled me to see him.

One day that I particularly remember, I saw him and he was carrying a teacup. That’s the story. There’s nothing else: just to see that man walking down the path, carrying a teacup. So I always say that’s one of my memorable moments of Suzuki Roshi, and people are usually waiting for some great story. But I just end by saying, “He was carrying a teacup.”

Tommy recovered his strength and rejoined the kitchen staff. There he was given more responsibility which he accepted reluctantly. Frances, the head cook, said,

It seemed he didn’t want to be directly responsible, which was strange, because he was actually the best at just getting things done. If you were in charge, then you’d take the heat, but Tommy was really good at getting work done.

Tommy’s reticence stemmed from several sources. For one thing, food mattered very much to Zen students. They had to wait three hours each morning to get any, they worked hard physically for hours each day, and they did a meditation built on mindfulness of body. The fact that diets like the macrobiotic, fruitarian, or lacto-ovo-vegetarian were fashionable at the time only accentuated the tendency toward food fixation. There really wasn’t much else to think about: radio and television signals couldn’t get over the ridges, and wouldn’t have been permitted in any case; such newspapers and magazines as did arrive came weeks late; drugs and alcohol were forbidden under penalty of expulsion; and there wasn’t adequate time for sex. But food—food happened three or four times a day. Students would drift by the kitchen to deliver reviews of a meal, together with their suggestions for improvement. Angie Runyon, another early Tassajara cook, once noted that when things were going well, students credited their meditation, and when things went poorly, they blamed the food. Whoever headed the crew for a meal was hero or goat, rarely neutral. Another reason Tommy hesitated to take responsibility was that he was unsure of himself; he knew that he hadn’t quite recovered from the disorientation visited on him by his drug use, particularly the psychedelics. He had strong ability to focus on a task at hand, and he had the right spirit about work, but he could lose the bigger picture. Angie spent time working with him, suggesting concrete sequences, and soon, she said, “I relied on him, and he was absolutely reliable.”

But if he inherited spaciness from the hippie days, he also brought with him some of that era’s best offerings: love, and acceptance of others. Angie said of him,

There wasn’t a sharp edge on him. I never heard a sharp word out of him. He was kind to everybody, and he encouraged everybody.

Frances described one scene in the kitchen when

I freaked out and lost it. I said I just can’t take it any more and I started to cry. Tommy stopped what he was doing, and came and put his arms around me. He walked me to my cabin, and put me to bed, and all the while we were walking, he kept saying, “I love you. I love you.” He did, too, that was the thing. He really did. It was like he was like your lover all the time.

He was completely sympathetic. There wasn’t anything you could tell him that would shock him. He had seen so much and done so much himself, that he just completely accepted you. Tommy was my best friend; he was a lot of people’s best friend.

At one of the next practice periods Tommy became the Head Cook, and here his warm-hearted style found full expression. He slowly developed a menu that satisfied the students’ emotions as well as their bodies:

I kind of extended things a bit: cream sauces—that had never been done before; I cut down on the brown rice; they used to serve soybeans every other morning. I stopped that. . .

He also brought a new atmosphere to the kitchen. Despite the previous cooks’ best efforts, problems had arisen: night raids on the kitchen by hungry students took place, food and ingredients turned up missing. . . One head cook had spent a few nights by the stove, guarding the next day’s gruel, and a visiting Zen master told the assembly to “put a lock on the doors and take them off your minds.” Tommy made sure they stayed off both places. Creating a warm, open feeling in the kitchen, he managed to defuse the awful tension about food, without sacrificing a sense of crispness in the work. He emphasized a kind-hearted approach, rather than a rule-oriented one.

To test their understanding, the six officers at Tassajara each gave a lecture to the assembly, followed by questions—a kind of Zen ritual resembling combat more than debate. Tommy was pressed on the point of vegetarianism:

Questioner:”Tenzo [Head Cook]! We are vegetarians, so we don’t kill animals. But we eat carrots and potatoes. What do you think about killing vegetables?”

Tommy: “Well, I definitely think we should kill them before we eat them.”

Another questioner probed his unnervingly open way.

“Tommy, have you learned to say ‘No’ yet?”

Tommy: “Nope.”

As his warm-hearted kitchen practice matured, so did Tommy’s sitting. He watched students slightly senior to him take initiations and ordinations in the Zen lineage of Suzuki Roshi. Because Tommy had experienced such a drastic uplifting of his life with Zen practice, and because he felt so personally committed to Suzuki Roshi, he thought of asking for ordination himself:

I went to him, and said, “Roshi, I was going to come here and ask you if I could become your disciple.” Because other people had been ordained by him, you know, but I just had patches on my pants, was completely green. So I said, “Now I realize that that was just an ego trip on my part. So I’m going to keep on practicing, and just do the best I can.” He said, “Well, there is no difference between that, and being my disciple.” That made me feel good. It encouraged me to continue practicing.

Related: Becoming Jivaka