When in doubt, bow. So I was told when I began Zen practice, and it’s advice I still follow. I’ve never forgotten the anxiety I felt then, new to the zendo and terribly afraid of making a mistake—tripping, belching, standing when I should sit or sitting when I should stand. I bowed a lot.

After a few years, I had a kind of dream. In the dream, I am standing in the bedroom of my small house. A man—unknown to me, almost faceless—is standing in the doorway, pointing a gun at me. I know I am about to die, and without thinking, I bring my hands together and bow. End of dream. Again, I am standing in the bedroom, a man points a gun at me, I place my palms together, make gassho, and bow. End of dream. Over and over, through an entire night, I had this dream, and again the next night, over and over—a death memory returned, ending in a bow.

My practice had begun to chip away at the enormous shell of pride around me. I saw that the self in the dream was something better than the self I was when awake. She was able to bow when there was nothing more to be done. When I bow now, I sometimes remember that: what it means to bow to the inevitable, to the obvious, to bow calmly. Even during the last breath, and the breath after that.

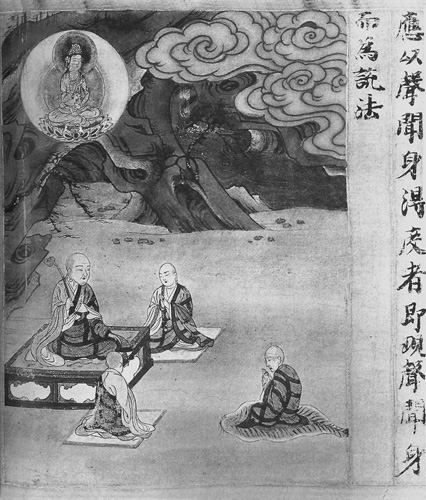

Now, I arrive at the zendo too late to join the meditation before the lecture and wait in the basement classroom below. At the end of the meditation I hear the distant ringing of a small bell, which ends with a rumbling thud of thirty bodies hitting the floor in prostration. A single tone, and thud! Two slow tones, and thud! And again, three times, and again, three times—the same low, rumbling thunder overhead. It’s habit now. My head drops and my hands rise up beside my face without a thought. Without a doubt.