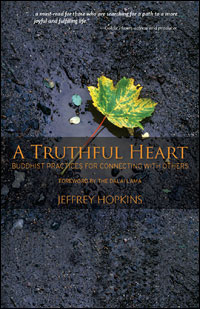

A Truthful Heart: Buddhist Practices for Connecting with Others

Jeffrey Hopkins

Ithaca, NY: Show Lion Publications, 2008

190 pp.; $14.95 (paper)

A VERY SICK FRIEND of mine asked me during a recent visit if I had anything I could read to him. At the time, the only reading material I had with me was an advance copy of A Truthful Heart, Jeffrey Hopkins’s new book on meditation practices for cultivating love and compassion. I hesitated at first; my friend is not a Buddhist, and since I had only glanced at the book at that point, I didn’t know what to expect. Hopkins, who served as the Dalai Lama’s translator for ten years, is a prodigious scholar whose other works tend toward the sort of massive tomes of textual analysis that can intimidate me from across a room. I didn’t want to bore my friend, of course, but I was more worried about how challenging and even threatening Buddhist ideas can be to non-Buddhists, especially one in my friend’s condition. I just didn’t feel ready to explain the ins and outs of karma and rebirth to someone who is probably only a few months from death, nor did I want to tell him to spend his remaining time learning how to cultivate compassion through meditation, even if I do think that would be a worthwhile use of it. Whatever my reservations, he expressed interest, so I read my friend and his caregiver one of the opening chapters, which boiled down to an introduction to contemplating the fact that, like ourselves, all beings want happiness and don’t want suffering. I seemed to be saying it over and over, and I worried that I was losing my audience, but by the time I was done, they were enthralled and asking for more. The chapter had sounded like Buddhist-reasoning-overload to my self-conscious ear, but clearly my fears were unwarranted—as an introductory argument for boundless compassion, dry and rational works.

Hopkins’s approach, especially in the early chapters of the book, is resolutely straightforward, laying out the basics of meditation and the numerous practices he recommends in a logical, down-to-earth manner, peppered with quirky anecdotes from his life and stories from his days with the Dalai Lama. The book is refreshingly methodical, organized to gradually lead the reader through the practices as deliberately as possible. He begins with cultivating equanimity through recognizing the simple fact, again and again, that we all want happiness and don’t want suffering. Having established this foundation, Hopkins leads us through a series of contemplative practices, all of which support the cultivation and practice of compassion. When a practice involves a more esoteric concept, such as considering that all beings have been our parents in previous lifetimes, he allows for skepticism, encouraging the nonbeliever to “play the game of rebirth.” The majority of the practices require no such compromise, however, and fit together so well as a progression that it all seems unquestionable. The beautiful comprehensiveness of the dharma, with its countless lists and multi-stepped elucidations, can overwhelm a reader, and start to go in one ear and out the other. Hopkins employs the greater levels of detail available to him skillfully, and it rarely feels like too much information as he takes the reader through concepts ranging from the eight confining conditions to overcoming fear through imagining dream monsters, from the dedication of merit to the Dalai Lama’s “favorite meditation,” a specific technique that encourages taking responsibility for the well-being of others.

The basic practice form that Hopkins most often employs is the three-tiered application of a specific contemplation first to your friends, then neutral people, then your enemies. This is meditation as a process of familiarization. There’s no need to throw yourself into the deep end of trying to feel kindness toward your enemies; start with your best friend, then your next best friend, then your third best friend, and so on, until you’ve really got the hang of it. Then do the same with neutral people. The operating assumption is that by drawing out the process and easing into each successive stage only when one is completely prepared, one is more likely to be able stick with it, rather than moving too quickly, never getting much depth, and losing interest, or just not feeling up to the challenge. This is asking a lot of our instant-gratification age. A tone as measured and deliberate as Hopkins’s is not often found in teachings geared to a Western audience—everyone mentions the importance of steady practice, of not looking ahead too much, but few illustrate it so clearly in writing. Hopkins can be repetitive, but it seldom feels unwarranted, and it is clear that the reader is getting an unusually unglossed picture of what committed practice entails. If boredom threatens once or twice, it is only a result of this realism—the fact is, everyone’s practice has its periods of tedium, to put it lightly. But the flip side is that it all does make sense when closely examined, and there are ways to deal with whatever comes along.

AT ONE POINT, Hopkins describes teaching a psychologist meditation and deciding in the beginning “that it would be better not to explain that we were aiming at becoming so close and responsible for others that we would seek enlightenment in order to free everyone from suffering and the causes of suffering and join everyone with happiness and the causes of happiness. So I suggested that instead of talking about the journey, we take it.” Although Hopkins relates this story almost as an afterthought, it is an apt description of his overall approach here. For so much of the book, he is relentlessly logical and practical, pounding into the reader’s head why and how this all makes so much sense. Ultimately, however, he must address just where this straightforward practice is leading, and he finally strays from the utterly practical into more esoteric Buddhist territory, presented without an alternate take. The buildup has been enough to prime the reader for less self-evident statements about compassion in Buddhist practice. Even so, Hopkins acknowledges how the aspiration to free all sentient beings may sound to many of his readers, practitioners and nonpractitioners alike: “If this does not strike you as mad, it is not appearing to your mind.” It is an unusual and savvy strategem, saving an explicit explanation of the bodhisattva ideal for page 183 of a book on Tibetan Buddhist practices for cultivating compassion. Asking “What would it be like to be such a person?” he reveals what all this practice has been preparing us for. Finally, the reader is faced with a scorching exposition of human suffering. Hopkins draws on seventh-century scholar Chandrakirti’s homage to the three types of compassion, beautifully portrayed in the images of a battered bucket in a well, the reflection of the moon in a rippling lake, and its reflection in still waters:

Contemplate: just as the bucket is tied by a rope to the wheel, so we are bound to past actions contaminated by the afflictive emotions of lust, hatred, and ignorance…. Just as the bucket is battered against the sides of the well, so we are battered by the sufferings of mental and physical pain, the suffering that occurs when pleasure leads to pain, and the suffering that comprises the mere fact of being caught in an afflicted process of conditioning. Powerlessly, sentient beings are wandering among bad states and better states.

As devastating as these revelations are, one realizes that the deliberate and regimented practices that make up most of the book have already established a confidence and understanding of how to face these hard truths. All too often, we start with the in-depth exploration of suffering, and it can be a dispiriting weight to carry the rest of the way; here, when we’re finally hit with it, there’s no denying how well prepared we can be if we follow his earlier directions.

This patient, calculated presentation of the dharma is likely the fruit of Hopkins’s years of training in the Tibetan Gelug school, known for its emphasis on monastic discipline and scholarly rigor. There is little, if any, entertaining exoticism to be found here, no tales of flying yogis or miraculous sudden enlightenment; while that very color and richness may be what draws many to Tibetan Buddhism, Hopkins seems confident that appealing to the rational mind can be just as powerful, if less sexy. His presentation of the material for a lay Western audience, almost subversive in its unassuming, plodding logic, is perhaps evidence of his years with His Holiness, that most skilled peddler of compassion—indeed, himself an official reincarnation of its embodiment, the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara—who consistently shows that when it comes to bringing the dharma to the West, the greatest guile is no guile at all.