I grew up in the South, and one of the people I was closest to as a girl was my grandmother Bessie. I loved spending summers with her in Savannah, where she worked as a sculptor and artist, carving tombstones for local people. Bessie was a remarkable village woman; she often served her community as someone comfortable around illness and death, someone who would sit with dying friends.

And yet when she herself became ill, her own family could not offer her the same compassionate presence. My parents were good people, but like others of their generation, they had no preparation for being with her as she experienced her final days. When my grandmother suffered first from cancer and then had a stroke, she was put into a nursing home and left largely alone. And her death was long and hard.

This was in the early sixties, when the medical establishment treated dying, like giving birth, as an illness. Death was usually “handled” in a clinical setting outside the home. I visited Bessie in a plain, cavernous room in the nursing home, a room filled with beds of people who had all been effectively abandoned by their kin—and I can never forget hearing her beg my father to let her die, to help her die. She needed us to be present for her, and we withdrew in the face of her suffering.

When my grandmother finally died, I felt deep ambivalence, sorrow, and relief. I looked into her coffin in the funeral home, and saw that the terrible frustration that had marked her features was now gone. She seemed at last at peace. As I stood looking at her gentle face, I realized how much of her misery had been rooted in her family’s fear of death, including my own. At that moment, I made the commitment to practice being there for others as they died.

Although I had been raised Protestant, I turned to Buddhism not long after my grandmother’s death. Its teachings put my youthful suffering into perspective, and the message of the Buddha was clear and direct: Freedom from suffering lies within suffering itself, and it is up to each individual to find his or her own way. But Buddhism also suggests a path through our alienation and toward freedom. The Buddha taught that we should practice helping others while cultivating deep concentration, compassion, and wisdom. He further taught that enlightenment is not a mystical, transcendent experience but an ongoing process, calling for intimacy and transparency; and that suffering diminishes when confusion and fear change into openness and strength.

My grandmother’s death guided me into practicing medical anthropology in a big urban hospital in Dade County, Florida. Dying became a teacher for me, as I witnessed again and again how spiritual and psychological issues leap into sharp focus for those facing death. I discovered caregiving as a path, and as a school for unlearning the patterns of resistance so embedded in me and in my culture. Giving care, I learned, also enjoins us to be still, let go, listen, and be open to the unknown.

As I worked with dying people, caregivers, and others experiencing catastrophe, I practiced meditation to give my life a spine on which to hang my heart, and a view from which I could see beyond what I thought I knew. I was grateful to find that Buddhism offers many practices and insights for working skillfully and compassionately with suffering, pain, dying, failure, loss, and grief—the stuff of what St. John of the Cross has called “the lucky dark.” That great Christian saint recognized that suffering can be fortunate, because without it there is no possibility for maturation.

Through the millennia and across cultures, the fact of death has evoked fear and transcendence, practicality and spirituality. Neolithic grave sites and the cave paintings of Paleolithic peoples capture the mystery through bones, stones, bodies curled like fetuses, and images of death and trance on cave walls.

Even today, whether people live close to the earth or in high-rise apartments, death is a deep spring. For many of us, this spring has been parched of its mystery. And yet we have an intuition that a fragment of eternity within us is liberated at the time of death. This intuition calls us to bear witness—to apprehend a part of ourselves that has perhaps been hidden and silent.

Giving care to a dying person and his or her family is an extraordinary practice that puts one in the midst of the unknowable, the unpredictable, the breakdown of life. It is often something that we have to push against. Physical illness, weakness of mind and body, being in the crosshairs of the medical establishment, losing all that the dying person has worked to accumulate and preserve—all these issues can be part of the hard tide of dying. A caregiver can be there for all of that, as well as for the miracles and surprises of the human spirit. And she can learn and even be strengthened at every turn. As we give care, we can enter onto a real path of discovery—if only we let ourselves. Whether caregivers are family or professionals, they walk a path that is traceless, humbling, and often full of awe. And like it or not, most of us will find ourselves on it. We will accompany loved ones and others as they die.

If we are fortunate, we will be present for our own death. A dying person can meet the precious companions of truth, faith, and surrender. Grace and space can enter that person like a river flowing into the ocean or clouds disappearing into the sky. For practicing dying is also practicing living, if we can only realize it. The more truly we can see this, the better we can serve those who are actively dying and offer them our love without condition. YEARS AGO, when I visited Biosphere 2 in Arizona, I asked the scientist taking me around why there were wires tied to the trees and attached to the Biosphere’s frame high above us. He explained that since there was no wind in the Biosphere, the trees had nothing to resist. As a result, they had grown weak and needed to be held up. Like our body and bones, we need something to resist against to make us stronger.

How then can we let the process of dying tear us apart and, by so doing, strengthen us? How can we truly be with dying, this invisible road of initiation that will open for all of us?

A spiritual practice can provide stability, which is as important for caregivers as it is for those of us actively dying. It can give us a refuge, a shelter in which to develop insight about what is happening both outside ourselves and within our minds and hearts. It can cultivate wholesome mental qualities, such as compassion, joy, and nonattachment—qualities that give us the resilience to face, and possibly transform, suffering. And a spiritual practice can be an island, a place where opening to uncertainty and doubt can lead us to a refuge of truth.

One dying woman described the experience of her meditation practice as being held in the arms of her mother. She said she wasn’t escaping from her suffering when meditating; rather, she felt met by kindness and strength. As she let go into her pain and uncertainty, she realized the truth of not-knowing in that very surrender. This experience gave her much greater equanimity.

Our own feelings can be powerful and disturbing as we sit quietly with a dying person, bear witness to the emotional outpouring of grieving relatives, or struggle to be fully present and stable as we face the fear, anger, sadness, and confusion of those whose lives are going through radical change. We may want to find ways to accept and transform the heat or cold of our own mental states. If we have established a foundation in a contemplative discipline, then we may find stillness, spaciousness, and resilience in the storm—even in the storm of our own difficulties around dying.

Following the breath for a few moments is the best way I have found to settle the mind and body and prepare for any more complicated or potentially arousing practices. Often I use the breath as the object of my attention, because this very life depends on it. Furthermore, you can discover your state of mind by the quality of your breath—is it ragged or tight, shallow or rapid? Often you can calm yourself by regulating your breathing. Whenever things get fraught or scattered, you can always return to the breath for as long as you need to ground yourself again.

A meditation practice offers us the sister gifts of language and silence, gifts that often come to us arm-in-arm to help. Language brings crucial insights, while silence is necessary for tapping into that deep concentration, tranquility, and mental stability within us. Contemplative strategies using language and silence prepare us both for dying and for caregiving. Some involve silence, focus, and openness, while others involve nurturing a positively oriented imagination, or cultivating wholesome mental qualities.

Often we feel that silence and stillness aren’t good enough when suffering is present. We feel compelled to do something—talk, console, work, clean, help. But in the shared embrace of meditation, a caregiver and dying person can be held in an intimate silence beyond consolation or assistance. When sitting with a dying person, I try to ask myself: What words will benefit this person? Does anything really need to be said? Can I know greater intimacy with her through a mutuality beyond words and actions? Can I relax and trust in being here without my personality mediating our tender connection?

One dying man told me, “I remember being with my mother as she was dying. She was old like I am now and was ready to go. I used to just sit with her, hold her hand . . . will you hold mine?” So we sat together in silence, with touch joining our hearts.

Where silence can hold a great intimacy, communication and words can serve to provide wisdom. We may rely on the gift of language—whether prayer, poetry, dialogue, or guided meditation—as a way to reveal the meaning in moments and things. Listening to the testimony of a dying person or a grieving family member serves the one speaking; it all depends on how we listen. Maybe we can reflect back in such a way that the speaker can at last really hear what he’s said. And bearing witness like this also gives us as listeners insight and inspiration. Language can loosen the knot that has tied a person to the hard edge of fear and bring one home to compassionate, heart-opening truths.

LEARNING ABOUT DEATH isn’t only for the dying—it is also for those who survive. Indeed, dying is not an individual act. A dying person is often a performer in a communal drama. Like our last will and testament, a legacy that materially benefits our survivors, we also leave a legacy of how we experience our death. And the bulk of that legacy comes from how we transition through the ultimate rite of passage—how we are able to be with our own dying.

Several years ago, Martin Toler, along with many other miners, died in the Sago Mine accident in West Virginia. Slowly dying in the thickening air of the mineshaft, the oxygen wicked up with every breath, Toler used what precious little energy he had left in his life to write a note of reassurance to those closest to him—and to the millions of us who later heard about it, too.

From deep inside the earth, Toler addressed the entire world, beginning his note: “Tell all—I see them on the other side.” He promises his kin to meet them in eternal life, in the place that is deathless. He expresses for all of us the deep human wish that our connections will transcend the event of separation we suffer at the moment of death. “It wasn’t bad, I just went to sleep,” the note continues, and scrawled at the bottom, with the last of his ebbing strength, are the tender, unselfish words “I love you.”

I have often sat by the bedside of dying people with their relatives close at hand, waiting for those last words of love and hope. Being on the threshold between life and death gives an aura of mystery and truth to the final utterances of the dying. We feel we can somehow penetrate the thin veil between the worlds through the words of the dying one; those so close to death might know what we all long to know.

Toler’s last words honor the noblest lessons from our human connections: that life is sacred and relationship holy. Through the darkness, he reached out, not only to his family, but to the rest of us through his abiding and compassionate words. For, as the Buddha told his cousin Ananda: The whole of the holy life is good friendship. Our relationships—and our love—are ultimately what give depth and meaning to our lives.

What message do we want to leave behind when we die? When poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning died, she uttered the word “beautiful.” “I am not in the least afraid to die,” exclaimed Charles Darwin. And Thomas Edison said only, “It is very beautiful over there.” These wise people on the threshold of death carry a message to the rest of us that death is our friend and not to be feared. What have they seen that we wish we could know? What is this mystery that all of us will enter?

All of these last words teach us how we can give over our spirit to the experience of dying—and how we may live in the meantime. They are testaments to the power of the human heart to transcend suffering and find redemption by encountering death fearlessly, and even beautifully. Thus, we come to understand the truth of impermanence, the intense fragility of all that we love, and that, in the end, we can really possess nothing. Yes, we may meet each other on “the other side.” Yet we may also ask ourselves: Can we meet each other now? Knowing that death is inevitable, what is most precious to us today?

We cannot know death, except by dying. This is the mystery that lies beneath the skin of life. But we can feel something from those who are close to it. Martin Toler said, “I love you.” He said, in effect: Everything is okay. In being with dying, we arrive at the natural crucible of what it means to love and be loved. In this burning fire we test the practices that can hold us up through the most intense of flames. Please, let us not lose our precious opportunity to show up for this great matter—indeed, the only matter—the awesome matter of life and death.

Exercise: How Do You Want to Die?

In teaching care of the dying, I often begin by asking questions that explore our stories around death, including the legacies we may have inherited from culture and family. Looking at our stories may reveal to us what we believe will happen when we are dying, and open new possibilities for us.

We begin with a very direct and plain question: “What is your worst-case scenario of how you will die?” The answer to this question lurks underneath the skin of our lives, subconsciously shaping many of the choices we make about how we lead them. In this powerful practice of self-inquiry, write it all down, freely and in detail – how, when, of what, with whom, and where you’ll die. Imagine your worst-case scenario. Take about five minutes to write from your most uncensored, uncorrected state of mind, and let all the unprescribed elements of your psyche emerge as you write.

When you are finished, ask yourself how you feel, how your body feels, and what emotions or sensations are coming up for you – and give yourself a few minutes to write down these responses as well. It is crucial at this point to practice honest self-observation. Then take another five minutes to answer a second question: “How do you really want to die?” Again, please write about this in as much detail as possible. What is your ideal time, place, and kind of death? Who will be there with you? And a second time, when you have finished, give some attention to what is happening in your body and mind, writing these reflections down as well.

If you can, do this exercise with someone else, so you can see how different your answers are. Your worst fears may well not be shared by others, and your ideas about an ideal death may not be someone else’s. My own answers to these questions have changed as time has passed. Years ago, I felt that the worst death would be a lingering one. Today I feel that it would be harder to die a senseless, violent death.

At a divinity school where I taught several classes on death and dying, one-third of the class answered that they wanted to die in their sleep. And in other settings where I have posed these questions, more people wanted to die alone and in peace than I would have guessed. Quite a few wanted to die in nature. Among the thousands of responses I have received to this question, only a few people said they wanted to die in a hospital, although that is in fact where most of us will die. And almost everyone wanted to die in some way that was fundamentally spiritual. A violent and random death was regarded as one of the worst possibilities. Dying painlessly and with spiritual support and a sense of meaning was considered to be the best of all possible worlds.

Finally, after exploring how you want to die, ask yourself a third question: “What are you willing to do to die the way you want to die?” We go through a lot to educate and train ourselves for a vocation; most of us invest a great deal of time in taking care of our bodies, and we usually devote energy to caring for our relationships. So now please ask yourself: What are you doing to prepare for the possibility of a sane and gentle death? And how can you open the possibility for the experience of deathless enlightenment at this moment and when you die?

Being With Death: Four Basic Practices for the Caregiver

No matter how busy you are, you can bring simple contemplative elements into your being-with-death practice that will help you fearlessly follow the dying person’s lead. Here are four basic practices to help you be with dying:

1. Share prayer

Sharing prayer or another contemplative practice with a dying person also serves the caregiver’s well-being. When you find yourself caught up in the events around you or in your own hope and fear, slow down. Even stop. Cultivate the habit of attending to your breath continually; use the breath to stabilize yourself.

2. Say a verse

You can also use words to generate a state of presence and self-compassion when you are with a dying person. For example, every line of the following verse is like medicine to me. I use it in my own practice, and share it with other caregivers and dying people. On the inhalation say to yourself, “Breathing in, I calm body and mind.” On the exhalation: “Breathing out, I let go.” Inhalation: “Dwelling in the present moment.” Exhalation: “This is the only moment.” I learned a version of this from the Vietnamese Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh many years ago. It has been a good friend since.

3. Come to your senses

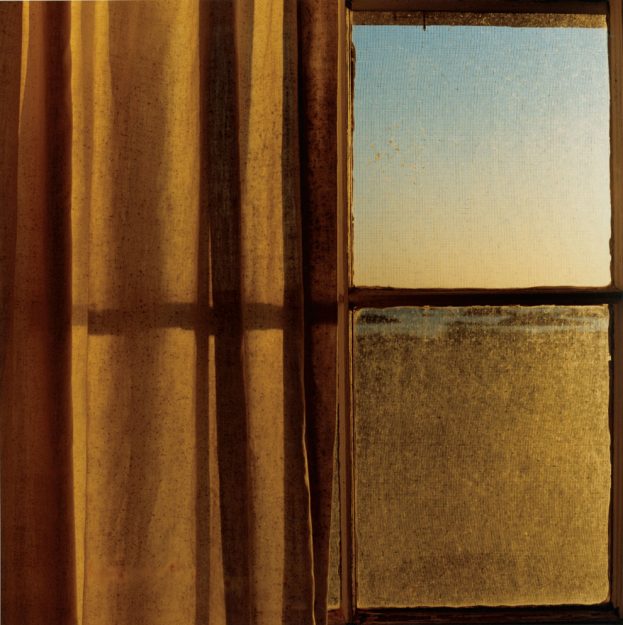

Another way to connect to the moment is to use your senses. Let them take you beyond your story into a bigger picture where you can follow the lead of the dying one and stay open and fearless. Look out the window at the sky for a moment. Listen attentively to the sounds in the room. Touch the dying person mindfully. Take a few sips of cool water. Breathe deeply and relax the tension in your body as you exhale. Remember why you are doing this work.

4. Practice motherly love

Tibetan Buddhists say that we have all been one another’s mother in a previous lifetime. Imagining every being as your mother isn’t always easy for many of us who have conflicted relationships with our mothers. But I can imagine a being who has given me and others life, protection, nourishment, and kindness. When I’m giving care to a dying person, I try both to give and receive kindness as if I were the dying one’s mother and to see the dying one as my mother, saying silently to myself, “Now it is time for me to repay the great kindness of all motherly beings.” Thinking of all beings with motherly love is a good reference point when I have fallen into automatic behavior, am feeling alienated, or am having trouble opening my heart.