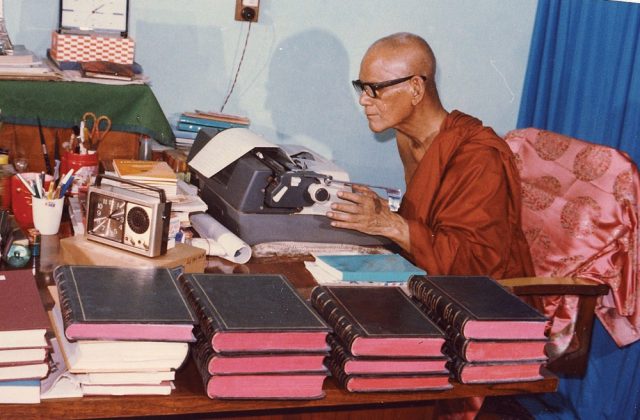

Regarded as one of the world’s most eminent meditation masters and Theravada Buddhist scholars, the Venerable Sayadaw U Pandita of Burma (now Myanmar) passed away on April 16, 2016, at the age of 94. Successor to Mahasi Sayadaw and spiritual adviser to Burma’s Nobel Peace Prize laureate and State Counsellor, Aung San Suu Kyi, Sayadaw U Pandita entered monastic life at the age of 12. Through decades of experience in the theory and practice of meditation, he cultivated in others the motivation to know and experience the taste of the dhamma, which he viewed as many times better than all the other tastes of the world. With this goal in mind, he established meditation centers throughout the world, working tirelessly to share the Buddha’s teachings in accordance with the instructions of Mahasi Sayadaw (1904–1982), encompassing both scripture and practice so that neither would be omitted. He lived as head teacher for eight years at the Mahasi Meditation Centre in Yangon, where the worldwide mass lay insight meditation movement began in 1947, until 1990, when he founded the meditation and study monastery Panditarama Shwe Taung Gon Sasana Yeiktha, also in Yangon.

In the months before his death, Sayadawgyi (as he was known in his latter years; the suffix -gyi means “great”) granted me a special invitation to discuss the “dhamma of reconciliation.” Over eight successive nights in February 2016, Sayadawgyi shared the wisdom that forms “Dhamma Advice to a Nation,” his final message to those seeking to heal from decades of brutal totalitarian rule in Burma. The following interview is a short excerpt from that material. While his is perhaps the most renowned and respected voice, U Pandita was but one of many of Burma’s “voices of freedom”—the courageous individuals who have fought tirelessly for human rights and democracy against the tyranny of one of history’s most vicious military regimes, often at risk of imprisonment, sometimes at the cost of their lives. And while the realities of our inhumanity to one another still threaten to drag us into realms alien and incomprehensible, the message of these voices, of freedom through reconciliation, comes from the front lines of a familiar and collective struggle for justice, dignity, and triumph over oppression in all its forms.

–Alan Clements

The following interview will appear in the forthcoming book “Aung San Suu Kyi and Burma’s Voices of Freedom in Conversation with Alan Clements” and its accompanying film highlighting those at the heart of Burma’s 28-year nonviolent revolution of the spirit.

It is common to react to violation with hurt, anger, outrage, and at times revenge. As we know, many millions of people in your country have been oppressed for over 50 years by a succession of dictatorships. What advice can you offer those who harbor feelings of hostility and retribution? How can one overcome those feelings and refrain from acting on them? Forbearance is the best. In this country we say, “Khanti [forbearance] is the highest austerity.” In the human world we are certain to encounter things we do not like. If every time one encounters difficulty there is no forbearance and one retaliates, there will be no end to human problems. There will only be quarrels.

To be patient and forbear fully, there must be the ability to reason, to think logically. Without forbearance, a fight occurs, both sides get hurt, and there’s no relief. Many wrongs are done. When one can forbear, the quarrel quiets.

In this, one needs to add metta—the desire for another’s welfare. When the desire for the welfare of others becomes strong, one can be patient and forbearing. When harmed, one can forgive, one can give up one’s own benefit and make sacrifices.

So to end the cycle of conflict, first neutralize one’s reaction? There are two kinds of enemies, or danger: the danger of akusala and the danger in the form of a person. Akusala are the unwholesome deeds that occur when lobha [desire, selfishness], dosa [anger, cruelty, hatred], and moha [delusion, stupidity] are extreme. These are called the internal enemy. They are also called the nearest danger because they are inside one’s own mind. Danger in the form of a person is an external enemy, a person who is hostile to us. The Buddha practiced to gradually weaken the internal enemies until they disappeared.

Related: A Perfect Balance

What is the basis, the spiritual or moral motivation, to refrain from committing unwholesome deeds, akusala? One should be as disgusted by akusala as one would shrink from picking up a red-hot coal. With a healthy disgust and fear, understanding that participating in unwholesome deeds brings trouble, one can refrain from wrongdoing.

Further, there should be consideration for others. One should spare others because one understands how they would feel if harmed. That is important. Hiri and ottapa [moral shame and moral fear] and consideration for others are the qualities that motivate one to refrain from performing unwholsome deeds.

Hiri and ottappa are also called the deva dhammas. Deva dhammas means dhammas [mental qualities] that make virtues brilliant. When one lacks these, one’s human virtues fade. The quality of behaving like a human being, being able to keep one’s mentality humane, having human intelligence, being able to develop special human knowledge—without moral shame and moral fear, all these human virtues fade. When one has these qualities, one’s virtues become bright. They are the dhammas that make human virtues shine. They are also called the lokapala dhammas. Lokapala means “the guardians of the world.” They preserve the world, keep it from being destroyed. What’s important here is one’s own individual world as well as the world around one. To the extent that these qualities are strong, one’s own world is secure, and equally, one no longer harms the surrounding world.

We know that if there isn’t some preventive measure to cure the delusions of the old guard, the very horrors of that old order—imprisoning people, torturing them, and denying them their most basic human rights—could easily recur. And generation to generation, we’d have the same problems. In your worldview, how do these dhamma attributes of forbearance and lovingkindness intersect with accountability and justice? Don’t we need accountability and justice for reconciliation to become real? Those who have done wrong should correct it by dhamma means, just like when a monk commits a monastic offense. They should make an honest admission: “This act and that act were wrong. I ask your forgiveness.” No matter how great the fault, with this, about half [the people] will be satisfied. They will have lovingkindness [for those who confess their wrong].

A hero, a person who is courageous, has the courage to admit one’s mistakes, one’s faults. Such a person also has the courage to do things that are beneficial for society. The most effective way to create peace among the people is for the oppressors to courageously admit their faults and reconcile with the oppressed. That is the best.

One should understand: wrongs done because of selfish greed bring only bad results. On the other hand, tasks done without selfishness, with lovingkindness and compassion present, bring only good results. One should understand the nature of good and bad results. If one knows neither the bad results of lacking lovingkindness or compassion nor the good results from having lovingkindness and compassion at the forefront, there is blind stupidity. There is darkness. And with darkness, one can’t see. As long as this understanding is absent, one lacks moral shame and moral fear.

And the cycle of oppression continues? Without moral shame and moral fear, there are unwholesome actions. With moral shame and moral fear, there are pure, clean, wholesome actions. That is important.

What should one do to prevent problems from occurring in the world? There should be both control and preservation, so that one’s personal world is not destroyed and the world outside one is protected from harm. And if the number of people were to become great who kept their own individual world from being destroyed by restraining unwholesome thoughts, speech, and actions, the world would become peaceful.

Another way to foster self-restraint is to have consideration for others. When there are thoughts, speech, and actions strong enough to cause suffering, reflect: Just as I do not wish to suffer, neither do others wish to suffer. As such, one avoids doing harm. Being able to put oneself in another’s place is very important.

Because people try to conquer others instead of gaining victory over themselves, there are problems. The Buddha taught that one should simply gain victory over oneself.

Do you have hope for real change here in Burma? Resistance power is important for everyone. People work to develop physical resistance to withstand heat, cold, and fatigue. For the most part, people give priority to developing physical resistance. There’s little concern for developing mental resistance. Of course, mental powers are also important. Nothing can be substituted for them.

One has to work to develop mental powers, to put focused energy into one’s mind. When one has developed mental resistance power, one can withstand the ups and downs one encounters. There is spiritual resistance, the strength to control one’s mind. is is needed by everyone. It is weak in the world today. But with the correct method it can be developed.

There are spiritual faculties that bring self-control, self-mastery. These need to be developed in order to have spiritual resistance. They are called indriya or bala in Pali. For developing these faculties, the path of satipatthana [practicing the four foundations of mindfulness: that of the body, of feelings, of the mind, of dhammas] is best. One can’t do this by meditating for just a short time. Only if one meditates meticulously, with real desire, can one can gain these spiritual faculties.

These faculties can be called spiritual multivitamins, like the multivitamins we take for physical health. When one develops the mind with satipatthana meditation, this is like taking spiritual multivitamins. If half the world would possess these spiritual faculties in themselves, the world would become peaceful.

You are aware that terrorism is an increasing problem all over the world. In my country of America, and in pretty much any Western and Asian country for that matter, there’s a deep and increasing fear of terrorism, whatever its ideological basis may be. My question: What advice might you offer to defeat radical extremism, which, I might add, in most cases considers success not only in the death of those whom they attack but in their own death as well? If you can’t overcome the internal enemies, they not only give you trouble but give others trouble too. And in future lives they also give you trouble. An ordinary, external enemy can’t debase you. If he or she kills you, it’s only in one lifetime. The internal enemies kill a being lifetime after lifetime. They also degrade one. They are quite frightening.

Related: Who Is the Real Aung Sang Suu Kyi?

Few people know that you are Daw Aung San Suu Kyi’s dhamma teacher. She looks to you for spiritual advice and guidance. I would like to follow up with the issue of national reconciliation, the centerpiece of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her new government’s vision of a peaceful and prosperous Burma. What is the dhamma of reconciliation? Human beings should have the courage to avoid doing what is wrong and the courage to do and to say what is beneficial. If one does something wrong, whether deliberately or out of carelessness, one needs to have the courage to admit one’s mistake.

The Pali word viriya means exactly this: the courage to avoid doing things that are wrong, the courage to do what is right, and if one errs, the courage to admit it. When taking such a moral risk, one must bear the suffering encountered. Such courage must be nurtured. It does not come quickly. You must develop it gradually.

In the realm of dhamma, whether one is a monk, a nun, or a layperson, there are rules and responsibilities. It won’t do to learn these duties and responsibilities only when one becomes an adult. They need to be learned from a young age. Just as one must try to make one’s IQ good, at the same time one must also try to make one’s SQ [spiritual intelligence] good. It won’t do to make SQ good only after one’s IQ has become good. It’s just like feeding a child. You must first nurse the baby and then all along the way, gradually, feed the child appropriately, taking into account the child’s age, size, growth, and, of course, both the quantity and quality of the food. Good health has many considerations; but first and foremost you must feed the child appropriately, starting from a young age.

Good parenting is the basis of good dhamma and the birth of SQ? Parents have the first duty to teach the child, and after them, teachers do. For the world to be peaceful, parents are crucial, because they are a child’s first teachers. Even in Myanmar, where Buddhism flourishes, because there are so many people who are ill-equipped to be parents, the dhamma has declined. Since the days of the Mahasi Meditation Centre—because I knew that many parents were not fulfilling their responsibilities—I’ve tried to teach children about Buddhist culture both in theory and practice, so that a new generation could emerge. This was a priority and remains so.

In America, a country where science and technology flourish, education or IQ has been given great emphasis, whereas moral behavior and emotional intelligence, or EQ, have been ignored. Because our country is doing the same as America—emphasizing IQ over moral behavior—teenagers are becoming immoral. Therefore, in our dhamma courses for children I emphasize SQ, spiritual intelligence, in order to strengthen it in them. I use the term SQ in place of IQ and EQ. SQ stands for sila [ethical intelligence] and sikkha [the threefold training in higher virtue, higher mind, and higher wisdom], as well as satipatthana. All three words begin with s.

In America, there is a lot of tension, stress, and depression. SQ is the best remedy? People with good SQ are able to control these feelings. They are able to maintain their discipline. In SQ, this refers to the five precepts of not killing, lying, stealing, or misusing sexuality, and refraining from intoxicants. Further, they have compassion for others and feel gladdened by others’ good characteristics. They aren’t jealous or envious. With respect to something to be done, they have the intelligence to evaluate whether it is beneficial or not and whether it is suitable or not.

It’s been more than 50 years that I have been teaching this program to the children. In essence, the children are taught, “those things are bad and they bring bad results.” Knowing that something is wrong, one shouldn’t fail in one’s duty to avoid it. “Those things are good.” Knowing what is good, one shouldn’t fail in one’s duty to undertake them. Not neglecting to avoid what should be avoided and to do what should be done. at is called appamada, or heedfulness.

Would you say more about the application of appamada? A person’s life is like driving a car. When driving one must stay in one’s lane, right? If one starts to swerve out of one’s lane, one has to correct this and straighten out. To be able to steer is essential. This ability to steer is called yoniso manasikara (wise consideration). The same can be said of a boat: you always have to control the rudder. And in order to steer well, you must learn to control the rudder. But for the most part, people cannot control their own lives. They’re without the ability to steer. Although they have a rudder, they can’t steer.

It’s also important to keep your mind humane, to keep your mind like a human’s mind should be. You can’t just look at what benefits you. You’ve got to look at what’s good for others, too. You have to do what is good for others as much as possible, and do it with an attitude of goodwill.

What is the importance of SQ for genuine reconciliation and harmony? When there is a difference of viewpoints, SQ is important for bringing about unity. People with good SQ are automatically straightforward, they automatically go the right way.

What advice would you care to offer the people who will either visit your country or who are looking for ways to understand and possibly help the people of Burma? It’s natural for people to help each other, and this should be done without self-interest. One shouldn’t want to get something out of it, and one should help with lovingkindness and compassion. When you give to another, it should be done with the attitude “May the person receiving this be happy to have it.” One must not boast to the world, “My country, my people, can help.” Only when help is pure and true does it truly help. It should be help offered without lobha, without greed, without selfish interest.

Further, both the giver and the receiver, although separated by different countries, should have the attitude they are related; one should have the attitude that one is helping one’s relatives. People from other continents are related to each other although their continent is different; they’re not related as continental relatives but as world relatives.

In addition to this way of being, the Buddha taught so that people can become related by the way of dhamma, related by dhamma blood. The dhamma is that which bears the dhamma bearer, the one who knows the correct method and puts it into practice. It lifts one up so that one doesn’t go down into the four lower realms of apaya [states of deprivation, according to Buddhist cosmology], and so that one doesn’t wander a long time in samsara.

This dhamma is what the Buddha searched for and found. People who have faith in the dhamma practice it, and through this practice are able to live happily in this very life as well as become free of existential suffering. People who reach this level of developing the dhamma blood within themselves become related by dhamma blood. Between them there is mutual understanding, trust, and friendliness. Additionally, they don’t make distinctions about nationality. They don’t have this attitude that “I am this,” or “I am this or that.” We’re all the same.

For us monks, whatever foreigner comes here to practice, if he or she practices the dhamma with respect and care, they become close, a dhamma relative. Only if people become related through dhamma blood will social problems gradually become weaker and weaker until finally people can gain peace.

The people of your country have suffered greatly. They have also inspired many of us in the world to become more courageous in transforming our own sufferings and, moreover, to put ourselves in the mind and body of others, to feel, and to act compassionately. What would you like to leave us as a final statement, to your people, and to everyone in the world? If one is born a human, it’s important to be a true human being, and it’s important to have a humane mentality. And one should also search for a way to come to know what is true, to know the true dhamma, and to walk the path of dhamma. One should walk this straight path, because if one walks it one will reach a safe destination. This is what’s really important, these three things.

In this regard, in the time of the Buddha there was a deva [a celestial being] who came to see the Buddha. He said, “The beings of the world are tangled up in a tangle, both inside and outside; who is it that can untangle this tangle?”

The Buddha’s reply was very simple. With sila, or morality, as a basis, if one works to develop samadhi and panna, or concentration and wisdom, to completion, then social problems will be resolved. That’s the essence. If that thrives within society, then there will be mindful interdependence. If that happens, the world will become a happy place.

Sadhu, sadhu, sadhu. Thank you, from my heart.

Thank the Buddha; they are the Buddha’s teachings.

Editor’s note, August 2019: Read Alan Clements’s recently published complete conversations with Sayadaw U Pandita in Wisdom for the World – The Requisites of Reconciliation and Mindful Advice to My Nation, freely available online.