David Chadwick

Penguin/Arkana: New York, 1994.

454 pp., $11.95 (paper).

One of the biggest challenges facing American Buddhism is the unease many feel toward its Asian cultural trappings. It’s the rare Nebraska farmer, for instance, who’s going to feel comfortable encountering Tibetan chants in a brightly colored temple festooned with thankas. This clash of cultures escalates when Americans schooled in the ideals of equality and democracy engage in the authoritarian formalities of many Buddhist sects.

It seems likely that as Buddhism finds its uniquely American expression, it will be divested of its Japanese, Tibetan, Chinese, Korean, Indian, Cambodian, and other accoutrements. But how to observe this often subtle phenomenon?

In medicine, a common tool of observation is the chemical tracer, like barium or a radioactive dye, inserted into an organism in order to highlight various aspects of the organism. This tool, as David Chadwick shows so well in his book Thank You and OK!, can be applied to the observation of social organisms as well, for in this engaging and often very funny report of his extended visit to Japan, Chadwick acts as a tracer of the first order, revealing by his very presence some of the impress of Japanese culture on Buddhism.

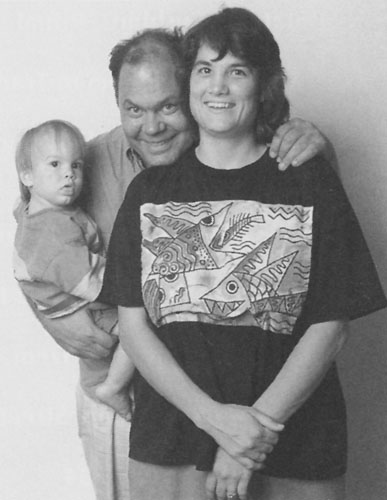

After more than twenty years of study in the United States under a series of Zen masters, including Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, Richard Baker Roshi, and Danin Katagiri Roshi, Chadwick in 1988 at last fulfilled his “long-held dream” of “seeing the country of my spiritual teachers” by moving to Japan for three-and-a-half years, including six weeks of intense training at a small Soto mountain temple he calls Hogoji, a pseudonym, with the rest of the time spent living next door to a large suburban Rinzai temple he calls Daianji.

Of the series of entries, the ones on Daianji will probably prove less compelling to readers interested strictly in information on Japanese Zen. Here, in addition to describing events at the temple, Chadwick devotes much attention to his secular relations with the Japanese, ranging from teaching English to housewives to dealing with Japanese ways of shopping, housekeeping, and childbirth to negotiating with governmental bureaucracies. He rarely chafes at, but with good humor nearly always marvels at, Japanese customs that differ from those in the United States. Japanese officialdom’s penchant for stickling exactitude, for example, manifests itself most hilariously during the author’s visit to the Driver’s License Test Building, where he undergoes the “transcendent experience” of responding to a battery of questions including “When did you take your first driving test?”; “What make of car did you take the test in?”; and “How many cc’s was the engine of the car?” Yet here, too, Chadwick is revealing something about the cultural biases of Japanese Zen, for he immediately precedes this entry with one depicting a fellow American at Daianji being ordered about, perhaps arbitrarily, by a younger, superior monk, and follows it with one about Hogoji in which Chadwick tries to follow tradition—the letter of the law—by ringing the bell for night zazen only when the lines of one’s hand are no longer visible, only to be faced with a rising quarter moon that threatens to keep the lines visible all night long.

The entries dealing with Chadwick’s brief stay at Hogoji are invariably fascinating, not only for the detailed description of the round-the-clock routine of Soto monastic life, but also for their unusually frank depiction of the butting together of American and Japanese Zen Buddhist heads. Though the author’s feelings become apparent when he deals with one visiting roshi, a sadistic and racist autocrat who replaces the Korean assigned to ring the bells with a Japanese, he generally keeps his own responses well in check, letting two other characters do the squabbling for him: Shuko, a Japanese monk enamored of every particular of Japanese Zen tradition, and Shuko’s nemesis, Norman, an American Zen priest determined to challenge nearly every aspect of that tradition. The battles between the two rage on, reaching a comic height when Norman climbs a tree and refuses to come down unless Shuko will give him permission to put pine nuts in the lunchtime rice. “‘The Buddha bowl is only for pure rice,’ Shuko pleaded….’There’s never been an exception.'”

Thank You and OK! isn’t just about cultural conflict. A dedicated Zen student for many years, Chadwick shares his own store of wisdom generously, though without preaching. Some of this wisdom comes in the way he tells his stories: he doesn’t divert his attention from the facts of life and death, and he takes a puckish pleasure in subverting pomposity. In the midst of his passionate homage to Katagiri Roshi (who dies during the course of the book), for instance, Chadwick mentions that, with few ice packs available in the Minnesota winter during which Katagiri died, the roshi’s body, “which was covered with flowers and herbs, lay in state in his simple casket on a bed of frozen bags of Bird’s Eye Tender Peas.”

At one point Chadwick asks,

Am I a failure because I can’t remember what Buddhism is—and are all the rest of us failures, as it seems, when contrasted against our early pure and simple expectations and the clear-cut enlightenment of the story books?

His answer, not surprising from a man who, as demonstrated throughout, is walking on the path of openness and acceptance, is a resounding “No.” “It seems to me that all our endless failures are adding up to a magnificent success. It’s just not what we had in mind. It’s real.” As real as this honest, heartfelt, searching book that instructs by inference and example and that, if as widely read as it should be, will help create the day when followers of American Buddhism will turn to their japanese elders and say, “Thank you and OK!”