Like many of my peers, I’d say I was called to chaplaincy. Following several years of retreat in the ’90s, I’d been living in the countryside overseas, working as a translator and teacher. Chaplaincy appealed as a profession where I might deepen my dharma practice by applying it to the kinds of situations I was naturally inclined to avoid and, hopefully, do my part to benefit people from all walks of life.

When I began formal clinical chaplaincy training in a large hospital in Philadelphia in 2011, I was the first Buddhist my seasoned Christian supervisor had worked with. Within the round-the-clock churn of that hospital, much of what I witnessed was a shock—the normalized violence, the lack of social safety nets, the many faces of anguish—and much was a blessing, beginning with the camaraderie of good people deeply dedicated to alleviating suffering against all odds. It took time to process the experience, but the call persisted. In 2014 I started a year-long chaplain residency at the University of Virginia Medical Center, working in palliative care and oncology. Again, the only Buddhist in the room.

Ever a backstage field, chaplaincy has been receiving a splash of media recognition in recent months, largely due to the crucial role that health care chaplains played during the height of the pandemic. For centuries the domain of Christians, the term chaplain is said to originate with the followers of Saint Martin, the 4th-century Roman soldier (later to become bishop of Tours, France) who cut his cloak (cappa) in half to share with a beggar. History tells us that in the United States, Abraham Lincoln himself appointed the first official Jewish military chaplain during the Civil War. Lieutenant Junior Grade Jeanette Gracie Shin, who signed her oath of office in 2004, was the first Buddhist chaplain in the Armed Forces. Modern chaplains—some of whom favor more inclusive terms such as pastoral or spiritual counselor—belong to any number of faith traditions, from Protestant to Pagan and from Hindu to Humanist, and are active in a variety of environments. While health care, corrections, education, and the military are the best-known employment sectors, first responders, assisted-living facilities, sports teams, corporations, and other organizations may also call upon chaplains when spiritual and emotional support are needed.

Today, just a decade since I dived in, Buddhist chaplaincy has become a “thing.” The profession offers an undeniable “right livelihood” appeal and myriad opportunities to practice nonjudgmental, compassionate presence, to slow-dance with the truth of suffering, and to lock eyes with impermanence and death. There are dharma-inspired chaplain-track degrees, certificate programs, and books for those looking to enter the field. It would seem that chaplaincy and Buddhism are a natural fit, but are Buddhist chaplains a good fit for Western society?

This core question piqued my interest and spawned a bunch of others. What training/education do Buddhist chaplains undertake? Who hires them? How up-front are they about their spiritual beliefs? How fluent in the Abrahamic traditions? How do they find each other to process and share? The answers were surprisingly elusive. Despite the field’s long history and recent expansion, there is little hard data about the current state of chaplaincy here. I was unable to find a reliable record of how many chaplains are currently working in the US, which education tracks or specializations are the most popular, or how well the different faiths are represented.

To try to find answers, I spoke with a number of peers representing a variety of sectors, backgrounds, and experiences about the particulars, challenges, and rewards of the vocation, beginning with Rev. Dr. Monica Sanford. Assistant Dean for Multireligious Ministry at Harvard, Sanford is a researcher with the Mapping Buddhist Chaplains in North America project, a multi-institution academic initiative (funded by Harvard Divinity School and under the umbrella of the Chaplaincy Innovation Lab) that looks to clarify these fundamental questions. In 2020, 425 of us answered an initial survey, giving several quantifiable insights into who we are and how we fit in.

Rev. Dr. Sanford and other team members presented preliminary findings last year. She told me that some of the survey results were unexpected, such as how many respondents had found employment on the basis of Clinical Pastoral Education alone. CPE, the program that was my entryway into the field, is the sanctioned training ground for professional chaplains and is generally a requirement for those destined to work in health care. Through accredited programs offered in clinical settings, often hospitals, small groups of students (cohorts) study, work, and review their experiences under a skilled supervisor. The Mapping survey showed that over half of Buddhists currently working or volunteering in chaplaincy had gone through CPE, a third or so had earned a graduate degree, and a quarter had attended a Buddhist chaplaincy certificate program—the three main training tracks for those who aspire to join the field.

It would seem that chaplaincy and Buddhism are a natural fit, but are Buddhist chaplains a good fit for Western society?

Traditional CPE is suffused with Christian values—a fact my Jewish comrades in Philly were quick to point out. For example, Christian chaplains often can’t conceive of pastoral care without God, salvation, and “hope,” a concept that many Buddhists find spiritually counterproductive. As one Catholic chaplain writes, “Hope is a theological language that references, in broad terms, the confidence in God’s ability to improve one’s circumstances. At the heart of this is a desire and conviction that things will get better.” In contrast, Buddhist teachings ask us to focus on remaining open to and working with whatever is arising in the moment.

Such differences in how Buddhists approach these issues may explain another finding in the Mapping study. The project identified three “Buddhist contributions to the field”: meditation (one’s own practice and the ability to guide others), presence, and a non-theocentric voice. This last of these contributions is proving increasingly beneficial in a society where more and more people define themselves as “spiritual” rather than “religious.” It is perhaps no surprise, then, that some Buddhist chaplains report finding themselves relegated to working with the “nones”—those who claim no religious affiliation.

“We never know who we’re going to meet or who we’ll be called by,” affirms Pamela Ayo Yetunde, JD, ThD, an author, pastoral counselor, co-editor of the award-winning anthology Black and Buddhist, and spiritual director of the Atlanta-based Center of the Heart. “We really don’t have the ‘luxury’ of dealing with preferences. We need to let go and be as close to a tabula rasa as possible.” In 2011, Yetunde proposed a model of pastoral care based on the Pali canon. (Her handbook is available at dharmacare.com.)

Yetunde believes that targeted programs can help us integrate dharma teachings and apply them to our work. “I’ve been a part of different Buddhist chaplaincy programs as a student, a founder, and a professor. I think that people who are wondering how they can incorporate Buddhist practice and philosophy in their lives in a way that is seamless, in that it’s not Buddhist over here and something else over there, won’t be disappointed with these programs,” she says. “They’ll learn skills about how to be their most compassionate, selfless selves, even if they decide not to become professional chaplains.” For those who do become chaplains, she points to the teachings on nondualism and nondiscrimination as being particularly helpful for chaplains in the field.

The ability to remain open and present is the mark of good chaplains everywhere, but for Buddhists it’s a calling card. Reverend Mildred Best, former Director of Chaplaincy at UVa, told me that she found that Buddhist CPE students—and there weren’t many of us over the years—were particularly good at offering spiritual care to those of other denominations. “You could see how their practice informed how they cared for people. They were good at holding sacred the patient’s experience of the divine, and patients appreciated it,” she said.

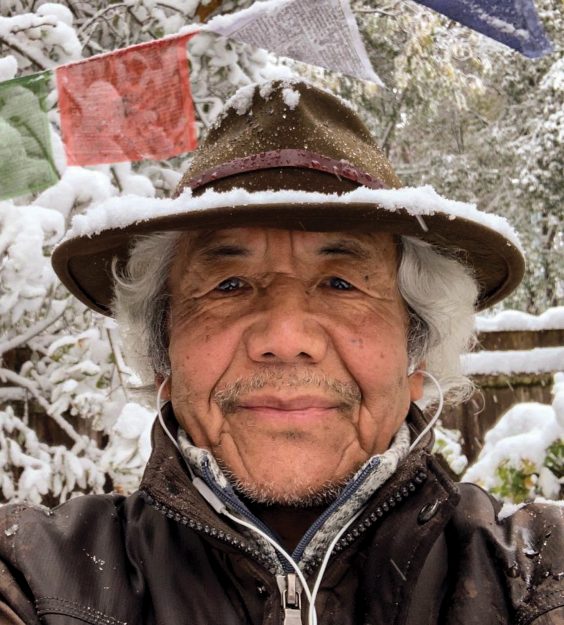

A good CPE program helps participants gain insights into other belief systems. Lama Tsering Ngodup Yodsampa credits CPE with helping him understand the Abrahamic mindset. Born in Tibet, Tsering passed through Nepal and Europe, where he served as a translator, before settling in the US. A chance meeting with a hospital chaplain got him interested in spiritual care as a career. “I asked her what a chaplain does. She said, ‘We provide spiritual support and prayers and so on.’ I said, ‘Oh! Is that a job?’ We do this all the time, but I’d never thought of it as a job!”

Tsering, who completed his CPE training a dozen years ago, says he clicked with his supervisor, a Catholic nun. “She was so authentic and compassionate and wise—not religiously uptight but very open. CPE helped me understand how Western people address situations of sickness, wellness, and death, as well as spiritual, emotional, and existential problems.” Had he received any pushback from his cohort? “A young monk in my first group struggled with what he’d read about Buddhism—he wondered how anyone could pray without a God to address. In the course of our group work he began to see how we can bring a sense of refuge to others.”

Now a staff chaplain at a large medical center in Boston, Tsering is active as a spiritual caregiver and meditation teacher working in a variety of settings. I wondered if his being Tibetan, and therefore presumably Buddhist, may make it easier for people of all backgrounds—patients as well as staff—to welcome his support. He said that while this may be true in some cases, in others there is simply a “healthy curiosity about spirituality” that fosters an interest in what the dharma has to offer.

It isn’t always that simple, especially in more conservative regions. Hospice chaplain Ann Marie (Shinko) Smith, a former special ed teacher whose personal experience of illness triggered an interest in meditation and led her to a pursue an MDiv and a career in pastoral care, urges those entering the field to ask themselves if they’re comfortable working in a Christian environment. “I would love to know what other Buddhists’ codes are when they’re serving mostly Abrahamic folk,” she says. “I’ve had to create a pretty elaborate code-switching thing so I can have a supportive conversation about God with a patient or family while remaining authentic and truthful, and I don’t think that most of our Christian colleagues are doing that code-switching.”

As another interfaith chaplain supporting hospice patients and their care circles in the Bible Belt, I’ve been working very hard at faith fluency. I tend to keep my views to myself and do my best to care for the other person’s spirit. The more I let go of any concepts about my identity and my truth, the more natural it feels to simply be with and support others. I’ve found that it’s much more about presence, heart, and letting go, and much less about being a Buddhist. As one chaplain so aptly put it, “I’m in service, not in sales.”

I heard similar reasoning from Jon Sallée, an educator who lives in Vermont—the “land of the nones”—and has joined the National Guard as an army chaplain candidate, despite how few people in the military identify as Buddhist. “I believe that you don’t come to chaplaincy because of your faith; you come because of the people you’re serving,” he said. “I find that Buddhism gives us a way of relating to other people’s faiths without judgment. Everyone has spiritual needs. When I say I’m a Buddhist it opens the door, and people who think and care about faith can feel comfortable talking to me.”

All told, the US military counts approximately three thousand active duty, noncombatant chaplains. Sallée is looking to join the rarified ranks of the Buddhists among them, most of whom are Asian, such as Chaplain Songkran Waiyaka (website MaintainTheMind.com) who currently serves at the army post in Fort Stewart, Georgia. Waiyaka, who was born in Thailand, offers pastoral counseling for military personnel and holds Sunday Buddhist services that are open to all and include yoga, chanting, and mindfulness.

Correctional chaplaincy is another field where the ability to facilitate meditation practice can be very beneficial for prisoners and staff alike. Secular mindfulness in particular has made great inroads in prison settings and by and large is no longer seen as a threat to Abrahamic values.

Karuna Thompson, MDiv, PhD, shares her experiences as a Buddhist chaplain at a maximum security penitentiary in Chaplains, a 2015 documentary seen on PBS. “All human beings are fundamentally good and awake, and these particular men who did these acts of violence could have been any of us,” she affirms. In 2001, when she was starting out, Thompson was the first minority faith chaplain and one of only two women to provide spiritual support in the entire Oregon Department of Corrections. She feels that a lot has changed since then (Oregon now boasts two Buddhist prison chaplains), in part because “there are enough Buddhists working in corrections now that the skepticism has been relieved and our intention to be of service to all people, whatever their faith—rather than to evangelize—is recognized.”

Early on, there were no endorsing standards for those on the outskirts of the Abrahamic model, and chaplains were expected to be ordained. “We needed to adapt our language and tradition to the dominant cultures,” Thompson says. The issue of how chaplains in all sectors come to be ordained and endorsed and what, exactly, that means speaks to the distinct variations among Buddhist denominations. Reserved for priests and monastics in the older schools, ordination has evolved in some traditions to include laypeople. There may be different degrees of commitment to the precepts within a given lineage. Further, many practitioners find inspiration in more than one tradition.

Until recently, those pursuing Buddhist chaplaincy focused primarily on finding ways to integrate systems that have been in place for decades. Some of us have been working directly with the prevailing professional institutions to make it easier for our experience and training to translate within the status quo. Now, others are looking to use the Buddhist perspective to advance and regenerate the field.

Reverend Joseph Rogers, MDiv, is a hospital chaplain in Los Angeles and an adjunct faculty member at University of the West; he has also worked in addiction recovery and in hospice, where he found the pace and expectations unsustainable. He believes that “Buddhist chaplains need to be much more than ‘religious care providers.’ If we don’t step into being spiritual counselors, if we don’t learn how to deeply hold space and listen to the suffering, we will ultimately be replaced by volunteers in an environment where economics are an increasing consideration.” True spiritual counseling, Rogers says, is about “seeing where a patient’s internal meaning-making system is either life-affirming or inhibitive to their well-being and to the crisis they’re in. How do we help them utilize their system to meet the challenges of where they are?”

Ayo Yetunde envisions chaplains becoming more active as public theologians, “not only healing hurt,” she suggests, “but also active in the space where the hurt occurs—disrupting and reversing that. We need to have a more public way of doing what we say we’re about.”

“It’s a fantastic career, and you will deepen your practice. But you will also feel isolated and alone, and you’re not going to earn a lot,” cautions the Mapping Project’s Monica Sanford. “And if you’re OK with all of that, then this could be the right thing for you. But you’ve got to be very realistic about what the job prospects are and proactive about building yourself a support network.

“Do you have a sangha that’s supporting you and can also act as an ethical check on your work? Compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma are things we have to deal with; who’s got your back? What community can you go home to at the end of the day? So many Buddhist chaplains out in the field feel very alone and disconnected—that’s been reported again and again. We have a good opportunity right now to begin building networks between Buddhists who are doing this work.”

“It’s a fantastic career, and you will deepen your practice. But you will also feel isolated and alone, and you’re not going to earn a lot.”

Chaplaincy Innovation Lab (CIL), a dynamic initiative that emerged from Brandeis in 2018, is helping bridge that gap for chaplains of all backgrounds. Its mission is to “bring chaplains, theological educators, clinical educators, and social scientists into conversation about the work of chaplaincy and spiritual care.” Their website offers ebooks, webinars, and a host of resources germane to the field, as well as pages specific to faith traditions, including Buddhism.

CIL led me to the Buddhist Chaplain Peer Circle, a recent initiative that follows Zen Center LA’s shared-stewardship model. BCPC states that its mission is to “create a temporary refuge and experience of sangha for Buddhist chaplains and caregivers that need a place to rest and connect with peers before continuing on their path.” To that end, it currently hosts monthly virtual gatherings. The long-term vision is to expand and deepen networking in order to support and connect Buddhist chaplains across traditions and roles.

It seems that we Buddhists are starting to come into our own in an evolving field where we have much to offer and much to learn. Yes, good jobs are hard to come by; yes, the work will push you to your limits; and yes, there will be more questions than answers. But if it’s your calling, you’ll find a way to make it work.