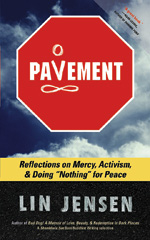

PAVEMENT: REFLECTIONS ON MERCY, ACTIVISM, AND DOING “NOTHING” FOR PEACE

Lin Jensen

Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2007

128 pp.; $12.95 (paper)

The pixelated online video shows a group of activists from Students for a Free Tibet at the base of Mount Everest, holding up a banner carrying the slogan of the 2008 Beijing Olympics, with one key addition: “One World, One Dream, Free Tibet 2008.” For their trouble, they would endure several days of very unpleasant Chinese custody. Now that’s activism, I thought to myself. Two months earlier, I’d been on retreat with the videographer, Shannon Service, in Colorado; now she was in a Chinese jail, a hero for the Tibetan cause. Shouldn’t I be taking action, too?

The common criticism that Buddhism and its practitioners are “detached,” more concerned with the nature of their minds than the state of the world, is pretty outdated in this era of engaged Buddhism and the high-profile activism of Thich Nhat Hanh and the Dalai Lama. Indeed, the intensity of Buddhist ideals makes me feel from time to time that I can’t possibly do enough to save the world, or at least that sitting on my cushion every day and attending the occasional antiwar rally just doesn’t cut it.

In a way, the sitting practice chronicled in Lin Jensen’s new book offers a solution: He hits the streets with a placard and a cushion. For more than two years now, Jensen has been sitting daily peace vigils in downtown Chico, California, meditating right there on the sidewalk. For a Soto Zen teacher and founder of the Chico Zen Sangha, this might have appeared at first to be a straightforward undertaking: be a peaceful presence, endure some name-calling with equanimity and compassion, go home. Jensen found it to be not so simple.

For one thing, I underestimated the extent of my own frustration, the urgency I felt over the continuing world violence—and often saw anger well up in me. . . . The conditions of the street made a student of me again, and the street’s first teaching was the most humbling. I could do nothing for peace unless I stepped aside. Peace was its own agent and I—at best—merely its instrument.

Appropriately, then, Jensen writes from the perspective of a student, finding a teacher in every stranger and challenge that comes along. As in his first book, Bad Dog, he writes episodically, an approach belying his interest in exploring the deepest truths of a particular situation and forsaking more drawn-out linear development. In Bad Dog, a memoir, Jensen skillfully draws the reader into the sensory world of his bleak youth on a turkey farm. In Pavement, most chapters are no more than four pages long, and many recount one-time sidewalk encounters. He describes these odd run-ins with all due color and detail—from the shouts and spittle of a large man named White Wolf to the woman who asks him to baby-sit her daughter while she goes grocery shopping—but the book isn’t about the characters he meets; it’s about the moment of meeting them, and what happens next.

The strength of Pavement lies in Jensen’s ability to get to the pith of these moments, moving from the event and its impact on himself and others to its deepest possible implications, weaving in Zen parables and past experience as necessary, all in the space of a few pages. A brown Lab that flops down next to him one day becomes a teacher of watchfulness, evoking memories of his time at a monastery, which lead to a reflection on opening to the needs of others, then the destruction wrought by Manifest Destiny, the need for watchfulness on a societal level, and finally back to the dog: “It might seem strange to count a chocolate Labrador retriever among my significant dharma teachers, but I wouldn’t know how to do otherwise.” In the hands of many writers, these connections might seem pat—if you really try, it’s not that hard to find the big dharma picture in anything—or they would devolve into a ramble. Jensen, fortunately, writes with clarity and a rare earnestness. His insights are not portrayed as easily come by, and thus they feel like experiences any one of us might go through with a little effort and clarity.

Jensen’s vigil turns out to be a peculiar and challenging form of practice. For most of us, dealing with the voice in our head during meditation is more than enough; Jensen winds up emceeing an open-mic night. But he’s not asking us to go sit on the sidewalk, and his commitment to activism, impressive as it is, somehow doesn’t elicit the guilt I felt when I learned that my friend was sitting in a Chinese jail. Jensen’s call to activism is a call to practice:

To be truly and wholly present even for the briefest moment is moment is to be vulnerable, without defenses of any sort. It is here that the boundary that fear constructs between myself and others dissolves. The heart is drawn out of hiding, and the inherent sympathetic response called compassion arises. I cease seeking my own personal happiness at the expense of others because I see that the suffering of others is my suffering as well, and I see too that my happiness is inseparable from that of others. Stripped of personal preference, I’m left exposed to the circumstance of the moment and find myself in the one place where I truly enter my life as it is.