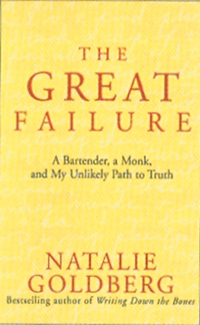

The Great Failure: A Bartender,

The Great Failure: A Bartender,

A Monk, and My Unlikely Path to Truth

Natalie Goldberg

San Francisco: Harper San Francisco,

September 2004

208 pp.; $23.95 (cloth)

The Great Failure recounts Natalie Goldberg’s deep disappointment with the two most important men in her life: her father, Ben Goldberg, and her teacher, the Zen Buddhist master Dainin Katagiri Roshi, who died in 1990. Although Goldberg has now published eight books, including a novel and a volume of poetry, she is best known for her immensely popular creative writing manual,Writing Down the Bones. This latest work is a well-intentioned, somewhat unfocused sequel to her 1994 memoir Long Quiet Highway, extending the earlier narrative with discoveries made in the intervening years.

A few years after the publication of Long Quiet Highway, a fellow Zen practitioner informed Goldberg that Katagiri Roshi had had illicit affairs with several students while serving as abbot of the Minnesota Zen Meditation Center, from 1972 until his death. The exact details remain hazy in the book, but it appears that Katagiri made oblique and often inept approaches to his female students. Looking back, Goldberg now suspects that her teacher was flirting with her in an awkward conversation they shared during a potluck dinner at her house, though she didn’t realize his intentions at the time and nothing came of the incident. As she recounts it, Katagiri’s advances were usually misunderstood or rebuffed, though in a few cases he was apparently successful.

Much earlier in her life, Goldberg’s father had failed her in other dark and disturbing ways. She quotes a letter she sent him as an adult:

You never knocked before entering my bedroom. You commented often at the dinner table about my young breasts and tried to kiss me on the lips in a way that made me uncomfortable. I carried constant anger around as a defense, to ward you off. You tried to peek at me when I was an adolescent, naked in the shower.

Later, Goldberg says of Katagiri’s behavior, “This was the same thing that happened with my father—different but the same.” However, while the pain she felt at these two betrayals is obvious, the connections between Ben Goldberg’s inappropriate parenting and Katagiri Roshi’s inappropriate teaching are never fully explored. The discussion floats along the surface of these powerful issues, interspersed with various mundane details of Goldberg’s life. There are moments of the clear, vibrant prose we have come to expect from Goldberg, including some amusing anecdotes about her failed attempts to explain Zen to her parents, but overall, the presentation is meandering and surprisingly flat.

Katagiri Roshi was part of that generation of Soto Zen teachers—including Taizan Maezumi Roshi, Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, and Kobun Chino Roshi—who arrived in California in the 1950s and ’60s, and profoundly shaped Buddhist practice in America. By now it is well known that in the course of spreading the dharma, virtually every Buddhist lineage has been touched by scandal. To anyone familiar with books like Shoes Outside the Door, Michael Downing’s account of Richard Baker Roshi’s infidelities at the San Francisco Zen Center, Goldberg’s shock at learning of Katagiri’s missteps will seem quaint, if not disingenuous. “I had made him perfect so I could feel safe to go deep and let my life bloom,” she writes. Students today no longer have that luxury.

The discussion of Katagiri Roshi’s flirtations is especially unsatisfying. Although Goldberg describes some perfunctory attempts to dig deeper into the reports of misconduct, her investigation does not go much farther than a few phone calls and a pointless dinner with one of the women involved. If something about Katagiri Roshi made his transgressions more startling or devastating than those of other teachers, Goldberg doesn’t tell us what it was. In fact, we too begin to wonder why no one found out about his behavior sooner.

The Great Failure is an immensely personal work and reads as if Goldberg followed her own advice to aspiring writers: letting the hand move continuously across the page, recording an unconstrained outpouring of memory and emotion. In the introduction she tells us she “wanted to learn the truth, to become whole,” and “to illuminate the path of honesty.” One can’t help but feel that it was a necessary and healing book to write. But not, alas, to read.