S. N. Goenka has been teaching Vipassana meditation for thirty-one years and is most widely known, perhaps, for his famous introductory ten-day intensive courses, which are held free of charge in centers all around the world, supported by student donations.

Born in Mandalay, Burma in 1924, he was trained by the renowned Vipassana teacher Sayagyi U Ba Khin (1899-1971). After fourteen years of training, he retired from his life as a successful businessman to devote himself to teaching meditation. Today he oversees an organization of more than eighty meditation centers worldwide and has had remarkable success in bringing meditation into prisons, first in India, and then in numerous other countries. The organization estimates that as many as 10,000 prisoners, as well as many members of the police and military, have attended the ten-day courses.

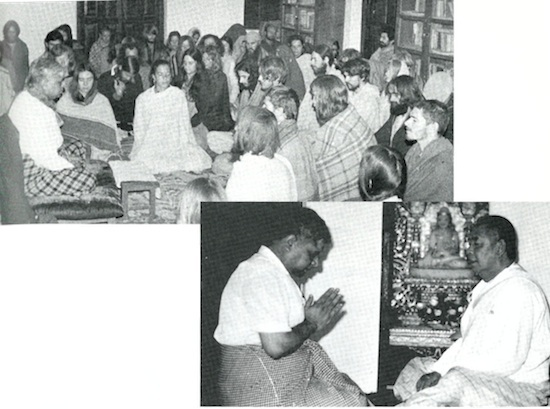

S. N. Goenka came to New York this fall for the Millennium World Peace Summit at the United Nations. He was interviewed there by Helen Tworkov.

According to some people, Vipassana is a particular meditation practice of the Theravada School; for others, it is a lineage of its own. How do you use the term? This is a lineage, but it is a lineage that has nothing to do with any sect. To me, Buddha never established a sect. When I met my teacher, Sayagyi U Ba Khin, he simply asked me a few questions. He asked me if, as a Hindu leader, I had any objection towards sila, that is, morality. How can there be any objection? But how can you practice sila unless you have control of the mind? He said, I will teach you to practice sila with controlled mind. I will teach you samadhi, concentration. Any objection? What can be objected to in samadhi? Then he said, that alone will not help—that will purify your mind at the surface level. Deep inside there are complexes, there are habit patterns, which are not broken by samadhi. I will teach you prajna, wisdom, insight, which will take you to the depth of the mind. I will teach you to go to the depth of the mind, the source where the impurities start and they get multiplied and they get stored so that you can clear them out.

So when my teacher told me: I will teach you only these three—sila, samadhi and prajna—and nothing else, I was affected. I said, let me try.

How is sila generated by watching the mind? When I began to learn Vipassana meditation, I became convinced that Buddha was a not a founder of religion, he was a super-scientist. A spiritual super-scientist. When he teaches morality, the point is, of course, there that we are human beings, living in human society, and we should not do anything which would harm the society. It’s quite true. But then—and it’s as a scientist he’s talking here—he says that when you harm anybody, when you perform any unwholesome action, you are the first victim. You first harm yourself and then you harm others. As soon as a defilement arises in the mind, your nature is such that you feel miserable. That is what Vipassana teaches me.

Related: Siddhartha, the Scientist

So if you can see that mental defilement is causing anxiety and pain for yourself, that is the beginning of sila and of compassion? If you can change that to compassion, then another reality becomes so clear. If instead of generating anger or hatred or passion or fear or ego, I generate love, compassion, goodwill, then nature starts rewarding me. I feel so peaceful, so much harmony within me. It is such that when I defile my mind I get punishment then and there, and when I purify my mind I get a reward then and there.

What happens during a ten-day Vipassana course? The whole process is one of total realization, the process of self-realization, truth pertaining to oneself, by oneself, within oneself. It is not an intellectual game. It is not an emotional or devotional game: “Oh, Buddha said such and such . . . so wonderful . . . I must accept.” It is pure science. I must understand what’s happening within me, what’s the truth within me. We start with breath. It looks like a physical concept, the breath moving in and moving out. It is true. But on the deeper level the breath is strongly connected to mind, to mental impurities. While we’re meditating, and we’re observing the breath, the mind starts wandering—some memory of the past, some thoughts of the future—immediately what we notice is that the breath has lost its normality: it might be slightly hard, slightly fast. And as soon as that impurity is gone away it is normal again. That means the breath is strongly connected to the mind, and not only mind but mental impurities. So we are here to experiment, to explore what is happening within us. At a deeper level, one finds that mind is affecting the body at the sensation level.

This causes another big discovery—that you are not reacting to an outside object. Say I hear a sound and I find that it is some kind of praise for me; or I find someone abusing me, I get angry. You are reacting to the words at the apparent level, yes, true. You are reacting. But Buddha says you are actually reacting to the sensations, body sensations. That when you feel body sensation and you are ignorant, then you keep on defiling your mind by craving or by aversion, by greed or by hatred or anger. Because you don’t know what’s happening.

When you hear praise or abuse, is the response filtered through the psychological mind to the bodily sensations, or is it simultaneous? It is one after the other, but so quick that you can’t separate them. So quick! At some point automatically you can start realizing, “Look what’s happening! I have generated anger.” And the Vipassana meditator will immediately say, “Oh, a lot of hate! There is a lot of hate in the body, palpitation is increased Oh, miserable. I feel miserable.”

If you are not working with the body sensations, then you are working only at the intellectual level. You might say, “Anger is not good,” or “Lust is not good,” or “Fear is not—.” All of this is intellectual, moral teachings heard in childhood. Wonderful. They help. But when you practice, you understand why they’re not good. Not only do I harm others by generating these defilements of anger or passion or fear or evil, I harm myself also, simultaneously.

Vipassana is observing the truth. With the breath I am observing the truth at the surface level, at the crust level. This takes me to the subtler, subtler, subtler levels. Within three days the mind becomes so sharp, because you are observing the truth. It’s not imagination. Not philosophy or thinking. Truth, breath, truth as breath, deep or shallow. The mind becomes so sharp that in the area around the nostrils, you start feeling some biochemical reaction that means some physical sensation. This is always there throughout the body, but the mind was so gross it was feeling only very gross sensations like pain or such. But otherwise there are so many sensations which the mind is not capable to feel.

Can you say something about the generation of wisdom? Is insight the same as wisdom? Same same same! Insight is not trying to understand the reality within myself merely at the intellectual level, but I understand it now at the experiential level. For anybody who admires Buddha’s teaching—that everything is impermanent, changing—this is at the intellectual level. Yes, everything’s changing. Nothing is permanent. Quite true. But that doesn’t help. When I practice Vipassana, I start with sensation: Look, sensation arises, seems to stay for some time but passes, is not eternal.

And after four, five, six days, the sensations get dissolved. There is no more solidity in the entire body. Mere vibration, very subtle vibration. So this impermanence is now experience. What is the purpose of reacting to something when it is changing so quickly? What is the purpose of reacting with craving or clinging? It passes away. Or hatred: it passes away. People who are very angry, or are full of lust, full of fear or full of depression or full of ego—when they keep on observing their sensations, the whole habit pattern changes.

Does the object of awareness ever disappear so that there’s only awareness of awareness itself? Exactly. But when I say I am aware of this object, and “I” is there, “I” am aware of this. This is a duality. Slowly as you proceed, “I” goes away. Things are just happening, and the knowing part knows. That’s all.

Is that the same as what some teachers call “bare attention”? Yes, this is bare attention.

When there’s no object. The object keeps on changing. What is the object this moment may not be the object the next moment. So whatever manifests itself from moment to moment, there is clarity. And there awareness means you are not reacting to it. Say the object, the sensation, is very pleasant. The old habit pattern was that when we feel this sensation we react with, “Ah, Wonderful! I must continue—this must be retained.” Then this is not bare awareness. But if you keep on, just awareness, let me see what happens, it changes. You are just observing the changing nature of the sensations. This sensation or that sensation, makes no difference.

Do you move to a place where there’s absolutely no self-consciousness of the awareness? That is a very high stage, the nirvanic stage. As long as we are in the field of mind and matter, sensation is bound to be there. But sensations will become subtler and subtler.

Is it possible to transcend awareness itself? Certainly. But that takes time. If you keep on thinking about this, it will be imagination. No imagination is allowed in the whole technique. Be with the present moment as it is. Otherwise you will be thinking: Nirvana, nirvana is like this, I must—You haven’t experienced nirvana. You’ve heard about nirvana, you’ve intellectualized about nirvana, you’ve emotionalized about nirvana. You don’t know what nirvana is. So let it come. Every moment is nirvana for you. Whatever is arising you are observing it—now it is passing away, now it arises. Bare awareness. That will take you to the stage where there is no more sensation, that is beyond mind and matter. Sensations come where there is mind and matter. And where there is no mind and matter there is no horizon, no passing, no sensation. But we can’t imagine it. The moment you start imagining, then it becomes a philosophy.

Do you understand this practice to be the essence of Buddha’s teaching? Yes. If proper attention is not given to the sensations, then we are not going to the deepest levels of the mind. The deepest level of the mind, according to Buddha, is constantly in contact with body sensations. And you find this by experience.

What is your role as the teacher? A teacher, out of compassion and love, seeing that somebody is suffering, gives a path. But each individual has to walk on the path. There is no magical miracle with the teacher. Totally out of the question. He only shows the path. That is the only role of the teacher, nothing else.

You’ve built this worldwide organization, and it seems that you don’t have a successor. So many are coming up, and to appoint somebody a successor will disturb the purity. Buddha never appointed anybody as a successor. Who am I to appoint? All these five hundred or six hundred teachers whom I have trained, they will carry on. If I am not there they will still carry on. Not because they have faith in the teacher—they have faith in the technique, which gives them results. That’s all that will remain. Otherwise they think so long as guru is there you get all of the benefits—guru is no more, it is gone: That is a personality cult. The technique is so great. It will survive. Don’t worry [laughs]. I am very confident. It will survive.

I wanted to ask you about criticisms in this country, specifically about your organization’s reported refusal to allow homosexuals to participate in advanced retreats. I don’t know how somebody started this talk, which is, I can say very confidently, totally wrong. We have no discrimination of any kind with anybody. It is totally out of the question. But of course when you go for deeper courses—twenty-day course, thirty-day course, forty-day course—it is a really deep operation of the mind, surgical operation of the mind. Deep-rooted complexes start coming to the surface, so every student must have the facility of privacy, a place to be without getting attracted to the object of passion. If somebody has got passion, and the object of passion is all the time there, then it might create a few difficulties. It has created difficulties sometimes even in ten-day courses. You have to be very careful.

I don’t know how this wrong thing started. There are teachers who are lesbians and homosexuals in this country and in Europe. Where there are facilities I teach them. When they go to a center where there’s not much facility and they say, I was refused there, so they write letters and say something bad about the teaching. They can’t understand. What about the facilities we are giving them? Just because one or two started complaining because they were refused—and there are other reasons also for refusing. I have refused those who are not homosexuals, who are not lesbians. Because at present this person is not fit for such deep operation. Even multi-millionaires, even there is one billionaire who is pressing hard to take a long course. I don’t give it to him. I say, No, you are not fit yet.

There has been some concern that the idea of not allowing these people into long courses is that they would act inappropriately. No, no, no! Anybody can act in a wrong way. If we separate people it is for their good, not for segregation, or denouncing them, saying: “Oh you’re not good, so I keep you separate.” It is for everyone!

Is it true that homosexuals have to renounce their sexual orientation in order to take the longer courses? Totally wrong. Of course we examine every person whether lesbian or not-lesbian, homosexual or not. If you are still a bundle of lust and you can’t control yourself so you can’t do a deeper operation of the mind, wait a little, take a few more courses. That is what we tell everybody. Not because someone is a homosexual.

In this country now, traditional practices—like segregating men and women, or variations on that theme—are becoming part of a mix, a melting pot. Some teachers welcome this challenge, but others are quite concerned about maintaining the purity of the various traditions. You are somewhat renowned for taking a strict view of maintaining the integrity of each lineage. Ultimately you have to take one decision. You want water, you dig ten feet, don’t get water, a different ten feet, you keep on digging in different places. Some day you must be sure I will get water here, then dig, come to that stage. I don’t say only remain with me. You try, and whichever path seems more compatible to your ideology, your thinking, go ahead. I don’t condemn.

In another example of traditions coming together, the peace summit that you’re attending at the U.N. this week is bringing world religious leaders together to make a declaration committing themselves to global peace. What’s your outlook? Any cause for optimism? When we look at Asia, we look at Burma, Sri Lanka, such violence and suffering in these Buddhist countries—how can we use our practice for peace? In centuries of Buddha’s teaching there is not a single incident where the followers of Buddha were involved in any kind of bloodshed in the name of propagating Buddha’s teachings. Wherever Buddha’s teaching went, it went with love and compassion. So that tradition says that here is a path which does not support violence or bloodshed.

Now you come to this millennium conference that is going on. Again, according to Buddha’s teaching and according to science, human science and the reality that we face, we want peace in human society. Certainly everybody, Buddhist or non-Buddhist, wants this. But how can there be peace in society unless there is peace in the individual? If the individual is boiling, agitated all the time, there is no peace. And you expect the entire society to be peaceful? To me it is unsound. Doesn’t sound logical.

Is it helpful to not use the word “Buddhism,” so it can become something for everyone? These are two words I have avoided in the last thirty-one years. In the thirty-one years since I started teaching I avoid using the word “Buddhism.” I never use the word “religion,” so far as Buddha’s teaching is concerned. For me Buddha never established a religion. Buddha never taught Buddhism. Buddha never made a single person a Buddhist.

Everybody will agree that every religion of the world has got these common factors, which I call the inner core of religion—morality, mastery of the mind, purification of mind. So I say this is the core, the wholesome core of every religion. And then there’s the outer shell. The outer shell differs from one to the other. Let everyone be happy with their rites, rituals—but they should not forget this inner core.

If they forget this and say, I am a religious person because I have done this rite, they are deluding themselves, they are deluding others.

In terms of this sense of interior peace: There’s a fear in this culture that if you are very peaceful that you’re a little dead. We want to be peaceful but cannot imagine how we can save the world, in terms of ecology, without being angry. We want to engage in life with those kinds of passions. I recognize that. I am not against that. People have not understood the Buddha’s teaching properly. Say a person comes to harm me, and I say, “I am a Vipassana meditator, like a vegetable, come and cut me”—that is not Buddha’s teaching. We will take strongest action wherever necessary, strongest physical and vocal action.

But before doing that we must examine ourselves at the physical level, at the sensation level, and the mental level. If I find my mind is very equanimous, I’ve got no anger towards this person. I’ve got love towards this person. But because this person does not understand soft language, I’ve got to use hard language. He does not understand soft action, I will take hard action. In his interest, in her interest. Love is there. Compassion is there. If there is anger, then I’m miserable. How can a miserable person help another miserable person?

This question requires a lot of clarification, because this question keeps coming up. That if you are not angry, how will we be able to defend ourselves? If we are not angry, how will be able to be successful in this way or that way? That is because people have not lived a life where they are detached and yet very strong. People feel that only with attachment I can gain my goal. But when they understand and they practice, a detached person is more successful to reach their goal. Because the mind is so calm, so clear. And whatever problem comes you can make a quick decision, a right decision.

And the government is introducing Vipassana into the police academy. Even prisoners change. Hard criminals. And every government wants a prisoner to be reformed when he comes to the prison. Instead of that it is a house of crime, where you discuss what kind of crime, and how you did it. They learn much more, and come out as bigger criminals. Now with Vipassana there is a big change.

And that is not by giving discourses, giving praises of Buddha. It is by technique, when they start observing. Living in the prison, most of the students have anger: So-and-so gave witness against me, when I get out I’ll kill him. Revenge. When they start observing, “Oh, what am I doing? I’m burning myself,” it goes away. With the other way this person will create more and more violence. Now he can’t do that. He’s full of love, full of compassion. And the person becomes so active. A number of hard criminals when they come out, they get jobs here and there and they don’t return.

Related: Free in Captivity

Do you think in the Buddhist societies today, where violence is being carried out, are they functioning with this detachment or no?

If somebody says they are a Buddhist and that is all they do, then I say you are a devotee of Buddha, you are not a follower of Buddha. It’s a real difference. You have great devotion towards Buddha, you say, “Lord Buddha, Lord Buddha, how wonderful!” But you don’t practice. Whether we keep calling ourselves Christian or Hindu or Muslim, it makes no difference. A follower of the Buddha follows the teachings: sila, samadhi, prajna. Those people who simply call themselves Buddhists are not living the life of Buddha. That is why I don’t use the word “Buddhist” or “Buddhism.” Buddha never taught any isms. In all his words, and the commentaries, which number thousands of pages, the word “Buddhism” is not there. So this all started much later, when Buddha’s teaching began to settle. I don’t know when it started, how it started, calling it Buddhism, but the day it happened it devalued the teaching of Buddha. It was a universal teaching, and that made it sectarian, as if to say that Buddhism is only for Buddhists, like Hinduism is for Hindus, Islam is for Muslims. Dharma is for all.