With this our 50th issue, we look back at how we got from there to here—year by year, issue by issue, teaching by teaching. Selected by Tricycle’s editorial staff, this collection is by no means comprehensive. But from the words of the Dalai Lama to the thoughts of the everyday practitioner, these excerpts offer a glimpse into the peculiar life of the dharma in the West.

1. Spalding Gray: I first read about Tibet in John Blofeld’s book, The People Flew. Did you ever see anyone flying in Tibet?

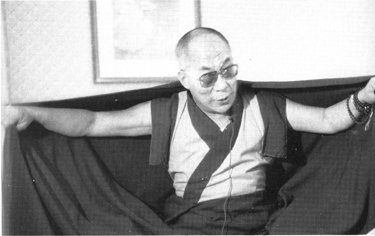

The Dalai Lama: No, but one thing surprised even me. One elderly nun who lives now in Dharamsala told me that when she was young, she spent a few months at a mountain place quite near Lhasa. She met there an elderly practitioner, around eighty years old, living in a very isolated area. She discovered he was the teacher for around ten disciples, and two monks among them were flying through the air off one side of the mountain. Now you see, they would fly using this part {holding up the sides of his robe}.

Spalding Gray: Like a hang glider.

The Dalai Lama: Yes, you see, she said they could fly one kilometer, with their arms out like this. She told me last year that she actually saw it. I was surprised, very surprised {laughter}.

—”Inside Out: The Dalai Lama Interviewed by Spalding Gray,” Fall 1991

2. I am obsessed with what I call “hag energy,” and am constantly on the scent of the ripened and withered female adept who cackles and rejoices in her freedom, going “beyond” her own vanity, grasping, fixation. —Anne Waldman

Vimala, the Former Courtesan, Speaks

I used to be puffed up

high on my good looks

intoxicated by a great complexion

my figure, my beauty . . .

I was very haughty, vain,

looked down on the other women

I was very young

Mutta Speaks

I’m free. Ecstatically free

free from three crooked things:

the mortar

the pestle

& my hunchbacked husband

all that drags me back is cut—cut!

—In celebration of “hag energy,” poet Anne Waldman updates translations of poems from the Therigatha, or “Psalms of the Sisters,” from the Pali Canon. Winter 1991

3. Set forth this mantra and proclaim:

Gate Gate Paragate

Parasamgate, Bodhi Svaha!

Gate, Gate means “gone, gone”; paragate means “gone beyond” (to the other shore of suffering or the bondage of samsara); bodhi means “the Awakened Mind”; svaha is the Sanskrit word for “homage” or “proclamation.” So the mantra means “Homage to the Awakened Mind which has gone over to the other shore [of suffering].”

—Mu Soeng Sunim, “The Heart Sutra: Three Commentaries on the Great Mantra,” Spring 1992

4. John Cage: The big difference between the city and the country is the sound of traffic and the sound of birds. Actually, I find the sound of traffic not as intruding, really, as the sound of birds. I was amazed when I moved to the country to discover how emphatic birds were for the ears.

Laurie Anderson: You mean because they range melody?

John Cage: No. Because they were so loud. And they really compete with the sirens when they fly around and come close …

Laurie Anderson: How has the response to your work changed over the years?

John Cage: Well, I don’t have to persuade people to be interested. So many people are interested now that it keeps me from continuing, really. I asked a former assistant a few days ago how I should behave about my mail that is so extensive and takes so much time to answer. If I don’t answer it honorably—I mean to say, paying attention to it—then I’m not being very Buddhist. It seems to me I have to give as much honor to one letter as to another. Or at least I should pay attention to all the things that happen.

Laurie Anderson: What did you decide to do about it?

John Cage: To consider that one function in life is to answer the mail.

Laurie Anderson: But it could take the whole day.

John Cage: But you see, in the meanwhile, I’ve found a way of writing music that is very fast. So that if we take all things as though they were Buddha, they’re not to be sneezed at but they’re to be enjoyed and honored.

Laurie Anderson: But this is a huge challenge.

John Cage: It’s a great challenge. The telephone, for instance, is not just a telephone. It’s as if it were Creation calling or Buddha calling. You don’t know who’s on the other end of the line.

—”Taking Chances: Laurie Anderson Talks with John Cage,” Summer 1992

5. The decline of the democratic ideal of freedom and the steady erosion of our civil liberties bears a noteworthy resemblance to the Buddhist pattern of decline: the rhetoric of morality and ethics over and against liberation and freedom.

6. Dying in the midst of modern technology is a complicated matter. Western medicine’s tendency toward aggressive treatment has joined with our cultural antipathy toward death to create an extraordinary situation: afraid of being caught alone and suffering in an impersonal technological nightmare, people are fighting for the “right” to die….

For the Buddhist, euthanasia raises new and demanding questions in light of traditional teachings. Theoretically, you can wind up in a situation where the precept against taking life and the commitment to compassionate action appear to be at odds.

—Patricia Anderson, “Good Death: Mercy, Deliverance, and the Nature of Suffering,” Winter 1992

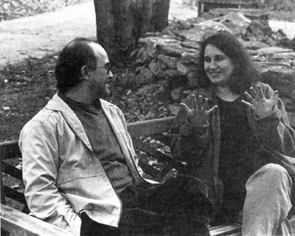

7. Author Stephen Batchelor interviews Sharon Salzberg, cofounder of the Insight Meditation Society, in Barre, Massachusetts. On the peculiar trait of “low self-esteem” that seems to afflict so many Westerners, Salzberg commented, “I asked the Dalai Lama a question about self-hatred. He had no idea what I was talking about. He was just astonished to learn that so many Americans experience that feeling. He asked, ‘Is that some kind of nervous disorder?'”

—”The Dharma of Liberation: An Interview with Sharon Salzberg,” Spring 1993

8. Buddha means the awakened one. Until recently most people thought of the Buddha as a big fat rococo sitting figure with his belly out, laughing, as represented in millions of tourist trinkets and dime-store statuettes here in the Western world. People didn’t know that the actual Buddha was a handsome young prince who suddenly began brooding in his father’s palace, staring through the dancing girls as though they weren’t there, at the age of twenty-nine, till finally and emphatically he threw up his hands and rode out to the forest on his war horse and cut off his long golden hair with his sword and sat down with the holy men of the India of his day and died at the age of eighty a lean venerable wanderer of ancient roads and elephant woods. This man was no slob-like figure of mirth, but a serious and tragic prophet, the Jesus Christ of India and almost all Asia.

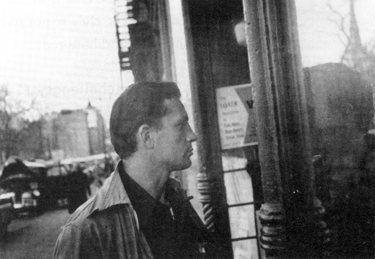

—Jack Kerouac, “Wake Up,” Summer 1993

9. Something about zazen must have reawakened some primordial longing, though I didn’t understand this at the time. I think most people who come to Zen practice have had

an early glimmering, an opening, of mystical experience, like a glimpse of the lost paradise. Perhaps they suppressed it or at least didn’t acknowledge it, afraid they were crazy, afraid of what others might say.They felt they’d be laughed at, as if they’d seen Bigfoot or something. But eventually they realize that something important has happened, and they go into a zendo to reaffirm this vision, know the truth. Why else would people go in there at dawn on a beautiful day and crack their knees all day long, when there are so many more tempting things to do in the so-called “real world”?

—”Emptying the Bell: An Interview with Peter Matthiessen,” Fall 1993

10. Recently I listened to a tape of {Katagiri} Roshi lecturing. I was amazed how difficult it was to understand him, how hard I had to concentrate. In the years I was with him I grew used to his English, and after a while it was fluent for me. Hearing the tape reminded me of how difficult it was for him. At the same time, how deeply he understood me, Jewish-American from Long Island, feminist, writer, rebel with a hippie past. How hard he worked to penetrate our culture.

Suzuki Roshi once said to the early hippies who came to him in San Francisco: “With your dress and long hair and beads, you all look alike. I can’t tell the difference. Shave your heads, get in black robes, and I can see your individual uniqueness.”

—”Face-to-Face with Natalie Goldberg,” Winter 1993

11. The importance of maintaining an enlightenment tradition extends far beyond the parameters of Zen and into the quality of American culture. Zen has no monopoly on understanding emptiness. World literature, East and West, is filled with expressions of unity and nonduality that attest to the universality of this insight. What is unique about the Zen tradition is its explicit focus on a rigorous methodology designed to prime this realization ….

The original enthusiasm for Zen in the United States was not just for personal discovery, but for the possibility of developing an appreciation for the unknown in an excessively cluttered society—it was an effort to break ground for new possibilities. What we need to know cannot arise from what we know now; our liberation from personal and collective suffering must derive from what we cannot envision, what is beyond our imagination, even beyond out dreams of what is possible.

One day an American student asked a Japanese Zen master, “Is enlightenment really possible?”

He answered, “If you’re willing to allow for it.”

—Helen Tworkov, “Zen in the Balance,” Spring 1994

12. Gossip is the unnecessary flapping of the jaw, sometimes fun, but mostly a waste of energy. Right speech is what points to liberation or helps alleviate suffering. In some sense, culture is gossip, and right speech is what cuts through it.

—Wes Nisker, “What Does Being a Buddhist Mean to You? Re: Right Speech and Gossip,” Summer 1994

13. Tricycle: So from the time of the historical Buddha until now, it is one long degeneration?

Gelek Rinpoche: Yes, definitely. That is why it is called “the degenerate age.” In rare cases one or two great people may come up, but you always look back on the lineage masters, at what great qualities they had. How they practiced, which always gets watered down. This is historical fact. In Tibetan Buddhism, earlier masters are so great that contemporary masters cannot ever think of putting their feet in their shoes. We are following in their footsteps, but we cannot fill their shoes.

Tricycle: Is part of your own optimism about Buddhism in America related to your acceptance of inevitable degeneration?

Gelek Rinpoche: I think that is a weak way of looking at it. I am optimistic because most Americans interested in Buddhism are very intelligent and their minds are open and sharp, which helps them understand, analyze, and do things. With that in mind I am very optimistic.

Tricycle: But are you not anticipating a great flowering of the dharma that will in any way shift the propensity of degeneration?

Gelek Rinpoche: I do pray for it.

—”A Lama for All Seasons: An Interview with Gelek Rinpoche,” Fall 1994

14. One of the more widely told Zen stories concerns the monk who carries a woman across a river. A while later, the monk’s companion chastises him for touching a woman, thus breaking one of the rules of his monastic order. “I put the woman down a long time ago,” he replies. “Why are you still carrying her?” This story is usually used as a metaphor for clinging of many different kinds. But I like to read it straight. As long as we avoid talking about sex with each other, we’re stuck in sex. Pointedly not talking about it is merely another kind of sexual obsession. When sex is mentioned in Buddhist texts, it’s almost always discussed in terms of “misconduct” or “obsession,” or “exploitation.” If we never talk about sexuality at all, if we don’t know what sexual rightness might be, how will we know what constitutes misconduct or exploitation?

—Sallie Tisdale, “Nothing Special: The Buddhist Sex Quandary,” Winter 1994

15. As the Buddhist view has consistently demonstrated, it is the perspective of the sufferer that determines whether a given experience perpetuates suffering or is a vehicle for awakening. To work something through means to change one’s view; if we try instead to change the emotion, we may achieve some short-term success, but we remain bound by forces of attachment and an aversion to the very feelings from which we are struggling to be free.

—Mark Epstein, “Shattering the Ridgepole,” Spring 1995

16. Some people think that one can become a buddha through meditation. This is wrong. The potential for Buddhahood is within your own nature. If it were true that Buddhahood depended on meditation, then if you stopped meditating after you became a buddha, you would become a common person again. The objective of practice is to be in accord with the natural way, so that your true nature can manifest itself. Just practice according to the methods taught by the Buddha and do not worry about being a success.

—Master Sheng-Yen, “Being Natural,” Summer 1995

17. Is there any cause for optimism? Well personally, yeah. Everybody’s got a life to lead and they’ve got a bodhisattva tendency, everybody wants to do good, so I just think on a personal level, yeah. On a larger scale, there doesn’t seem to be any hope unless compassion becomes a more widespread important teaching on how to live. Compassion to self and others.

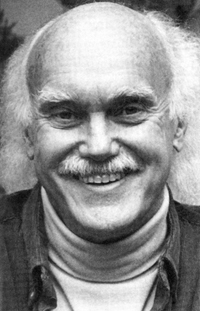

—”Spontaneous Intelligence: An Interview with Allen Ginsberg,” Fall 1995

18. If you think that becoming a monk is some kind of withdrawal, a sort of asceticism in terms of forcing yourself to do certain things, and not to do others, then that is a problem. The aim of renunciation is freedom. That was the experience I had when I took vows—this incredible feeling of freedom. It felt like a bird suddenly took off in the sky, like being released from all bounds. I think that’s the only way you can remain a monk, if you enjoy that sort of feeling.

—”Released from All Bounds: An Interview with Konchog Tendzin,” Winter 1995

19.

—Frank Olinsky, Spring 1996

20. Well, you know, it would be absurd to think as you’re going to sleep, ”I’m practicing tantra,” just because you’re going to sleep. But it would also be silly to cut yourself off from the possibility of experiencing those deeper states by thinking, ”I’m not practicing tantra.” So, in sex, it would be really silly to run around claiming that we—who don’t have that much development of compassion and realization of emptiness and so forth—claim that somehow we’re practicing tantra, or when we’re angry that we’re being like a wrathful deity. That’s really sick. But sometimes an ordinary person can start paying attention to the entity of the mind in the midst of anger. And that probably can only be done if you don’t have the inflated thinking of “I’m practicing tantra.” And the same with sex.

—”In the Realm of Relationship: An Interview with Jeffrey Hopkins,” Summer 1996

21. The Tricycle Poll

Psychedelics: Help or Hindrance?

Number of responses; 1,454

63% from the magazine

37% from www.tricycle.com

89% said that they were engaged in Buddhist practice.

83% said that they had taken psychedelics.

Over 40% said that their interest in Buddhism was sparked by psychedelics, with percentages considerably higher for boomers than for twenty-somethings.

24% said that they are currently taking psychedelics, with the highest percentages for people over 50 and under 30.

41% said that psychedelics and Buddhism do not mix.

59% said that psychedelics and Buddhism do mix. The age group that expressed the most confidence in a healthy mix was under 20.

71% believe that “psychedelics are not a path but they can provide a glimpse of the reality to which Buddhist practice points.”

58% said that they would consider taking psychedelics in a sacred context. (In the “under 20” catego this percentage was 90%.)

—from the Special Section on Buddhism and Psychedelics, Fall 1996

22. You made popular in this country the expression “don’t know mind.” Could you say what that is? Human beings understand too much. But what they understand is just somebody’s opinion. Like a dog barking. American dogs say, “Woof, woof.” Korean dogs say, “Mung, mung.” Polish dogs say, “How, how.” So which dog barking is correct? That is human beings’ barking, not dog barking. If dog and you become one hundred percent one, then you know sound of barking. This is Zen teaching. Boom! Become one.

—”Boom! An Interview with Zen Master Seung Sahn,” Winter 1996

23. “Which would you rather do? Go to the Queen’s croquet game, or get enlightened?” {asked the Cheshire Cat}.

Alice did want very much to go to the croquet game, but this was a grown-up-sounding question, so she felt it required a grown-up-sounding answer. “Oh. To get enlightened, of course,” she said with a knowing air.

The Cat’s eyes bulged out for a moment again, and then it said, “Well, in that case, you won’t get enlightened.”

This surprised Alice, who responded, “You mean if I want to get enlightened, that will keep me from getting enlightened?”

“Precisely,” said the Cat. “The desire to get enlightened is the one thing that will keep you from being enlightened.”

“Well, then, in that case,” said Alice, ”I’d rather go to the Queen’s croquet game.”

“No, no,” said the Cat, “that won’t do either, If you want to play croquet so that you can get enlightened, that will keep you from getting enlightened, too.”

“But whatever on earth should I do, then?” said Alice, beginning to feel a little giddy from all the strange ideas she had heard since this morning.

“There’s nothing to do at all,” replied the Cat. “Enlightenment isn’t something you do, it’s something you simply are. All you need to do is remind yourself that you’re enlightened and then act naturally in an enlightened way.”

“But how can I know what’s an enlightened way when I’m not yet enlightened?”

The Cat rolled its eyes and replied, “Mercy, how can you be so ignorant, child? You’re already enlightened. You’re enlightened, I’m enlightened, the Mad Hatter, the March Hare: We’re all enlightened.”

“But if I’m already enlightened, why don’t I know…”

“Well, of course you know. I just told you so,” replied the Cat, its grin growing steadily broader….

—P.B. Law, “Alice in Enlightenedland,” Spring 1997

24. After I have attained nirvana, during the first five hundred years there will be many living beings who will practice my teachings and gain liberation. During the second five hundred years there will be many who will practice meditation. But even though kinds and ordinary peole will believe in and practice the true dharma, eventually such people will become few. During the third five hundred years there will appear many teachers who instruct people in the true dharma, serve as leaders for living beings, and cause them to attain liberation. But shravakas and arhats will become few. Kings, ministers, and ordinary people will be reduced merely to listening to the teaching; they will not take it to the heart and practice it, nor will they exert themselves, and their faith will decrease. The protectors of the true dharma will be displeased, and the power and influence of those who do not believe in the true dharma will increase. The kings of this world will lead armies to and fro in battle against each other, and the forces of evil will increase.

—Jan Nattier quoting the Buddha in “The Death of the Dharma: The Buddha’s Prophecy,” Summer 1997

25. We came into the world without husband, wife, friend, or companion. We may have many friends and acquaintances at the moment, and perhaps many enemies, too, but as soon as death falls upon us we shall leave all of them behind, like a hair pulled out of a slab of butter.

—Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, “Like a Hair Pulled Out of Butter,” Fall 1997

26. The Buddha said that defilement {mental qualities that obscure the clarity of the mind: passion, aversion, delusion} is like a wide and deep flood. But then he went on to describe the practice of crossing that flood as simply abandoning craving in every action. Now, right here at feeling, is where we can practice abandoning craving.

Bring the practice close to home. When the mind changes, or when it gains a sense of stillness or calm that would rank as a feeling of pleasure or equanimity, try to see in what ways the pleasure or equanimity is inconstant, how it’s not you or yours. When you can do this, you’ll stop relishing that particular feeling. You can stop right there, right where the mind relishes the flavor of feeling and gives rise to craving. This is why the mind has to be fully aware of itself—all around, at all times—in its focused contemplation, to see feeling as empty of self.

—Upasika Kee Nanayon (1901-1978), one of twentieth-century Thailand’s foremost women dharma teachers and poets. From “A Glob of Tar,” Winter 1997

27. Yes, I think Westerners lack respect for their own spiritual maturity. It’s as though Asia owns spirituality, and we’re these barbarians, beseeching, “Oh, Bhante, please come over and tell us how to live.” But I’ve been to Asia, and they’re just as screwed up as we are. And there’s some real wisdom in our culture; the West has a tradition, too, of compassion and wisdom. And some people who aren’t even religious have it. When I was in Asia I totally did whatever an Asian layperson would do—I have the deepest respect for this tradition—but Asia does not have a monopoly on kindness. In Asia, being a layperson is—from the point of view of meditational practice—considered second class. I personally think that the monastic life does optimize your possibilities for breaking through to awakening. But it’s by no means a guarantee. Most monasteries are hardly crammed full of enlightened people.

But we need a teaching that addresses the lives we actually live. We do need to handle money. We are in relationships. We do need to eat more than once a day. The problem isn’t eating or sex or money; it’s that we don’t know how to use these energies. The monastic strategy is: Don’t touch it; it’s dangerous. So the monks don’t handle money, etc. To me that’s not in and of itself particularly holy. It’s a strategy, a monastic strategy to get free. I’m all for it—if you’re going to be a monastic.

—”The Art of Doing Nothing: An Interview with Larrry Rosenberg,” Spring 1998

28. Many Zen practices are about suppression—sheer concentration and shutting out things. I realized that what you shut out is exactly what turns around and runs you. So I began trying to get students to work in a different way, and it proved to be effective.

Dogen [the thirteenth-century Zen master] said that to study Buddhism is to study the self. To study the self—your thoughts etc.—is to foget the self. And to foget the self is what? It’s to be enlightened by all things.

Suppose somebody has hurt my feelings—or so I think. What I want to do is to go over and over and over that drama so I can blame them and get to be right. To turn away from such thinking and just experience the painful body is to forget the self. If you really experience something without thoughts, there is no self—there’s just a vibration of energy. When you practice like that ten thousand times, you will be more selfless. It doesn’t mean that you’re a ghost. It means that you’re much more nonreactive, in the world but not of it. Dualism transforms into nondualism, a life of direct and compassionate functioning.

—Charlotte Joko Beck, “Life’s Not a Problem,” Summer 1998

29. In a state of mindfulness, you see yourself exactly as you are. You see your own selfish behavior. You see your own suffering. And you see how you create that suffering. You see how you hurt others.

—Bhante Henepola Gunaratana, “Mindfulness and Concentration,” Fall 1998

30. For thirteen years I was a law enforcement offIcer. In the dark humor of that environment, we called ourselves “paid killers for the county,” No one else wanted to be in our boots. I did not identify myself as a Buddhist; I was not aware that the way I behaved and experienced the world fit squarely with the Buddha’s teachings. It is clear to me now that we could have been, and were, instruments of karma. But skillful action, discriminating awareness, karma, the law of causality were not terms in law enforcement basic training.

For a Buddhist in police work, the most important thing is to be constantly aware of ego. It is not your anger, not your revenge, not your judgment, no matter how personal the event. I was paid and trained to take spirit-bruising abuse. I endured things of which the majority of women in America will never even dream. For me it was not judgment, in the Western sense, but discernment. This kept me, and others, alive and healthy. This discernment allowed me to act skillfully in crisis. The law of causality allowed me to know that if I could not stop the perpetrator of violence or pain or loss, that some other vehicle would reach that person—karma.

—Laurel Graham, “Vajra Gun,” Winter 1998

31. What is the experience of true compassion? While recognizing mind essence, there’s some sense of being wide awake and free. At the same time, there’s some tenderness that arises without any cause or condition. There a deep-felt sense of being tender. Not sad in a depressed way, but tender, and somewhat delighted at the same time. There’s a mixture. There’s no sadness for oneself. Nor is there sadness for anyone in particular either. lt’s like being saturated with juice, just like an apple is full of juice.

—Tsoknyi Rinpoche, “Dissolving the Confusion,” Spring 1999

32. There’s no school that says “Cling.” Liberation is about cutting, or dissolving, or letting go of, or seeing through—choose your image—the attachment to anything. The description of the mind of no-clinging may be different in the different schools, but the experience of the mind of no-clinging is the same. How could it be different?

—”How Amazing! An Interview with Joseph Goldstein,” Summer 1999

33. Working intimately with a teacher is the same as learning to stop shielding ourselves from the completely uncertain nature of reality. All the ways that we hold back and shut down, all the ways that we cling and grasp, all our habitual ways of limiting and solidifying our world become very clear to us, and it’s unnerving. At that painful point, we usually want to make the teacher wrong or make ourselves wrong or do anything that is habitual and comforting to get ground back under our feet. But when we make an unconditional commitment to hang in there, we do not run away fron the pain of seeing ourselves—and this is a revolutionary thing to do and it transforms us. But how many of us are ready for this? One has to gradually develop the trust that is ultimately liberating to let go of strongly held assumptions about reality.

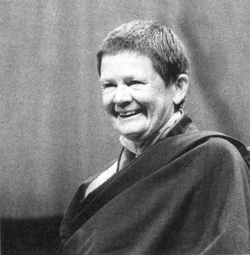

—“Unconditionally Steadfast: An Interview with Pema Chödrön,” Fall 1999

34. Famed spiritual teacher Ram Dass, interviewed by Tricycle two years after a debilitating stroke: “One of the things my guru said is that when he suffers, it brings him closer to God. I have found this, too.”

—”Stroked by the Guru: An Interview with Ram Dass,” Winter 1999

35. If you think the best way for Buddhism to help America is not explicitly as Buddhism, then what is the point of being Buddhist? There is no point in being Buddhist! One does it for the sheer joy of swimming in the infinite!

—”Swimming in the Infinite: An Interview with Robert Thurman,” Spring 2000

36. True dharma practice is a revolutionary activity, and you can’t do it in a comfortable way.

—”The Sure Heart’s Release: An Interview with Jack Kornfield,” Summer 2000

37. Gardens are not created or made, they unfold, spiraling open like the silk petals of an evening primrose flower to reveal the ground plot of the mind and heart of the gardener and the good earth.

—Wendy Johnson, “The Eightfold Garden,” Fall 2000

38. So I started sitting retreats and I started working with the steps [of Alcoholics Anonymous]. I eventually took a two-year vow of celibacy when I was twenty—in my prime! [laughs]—and went from being an indulgent addict to the other side: celibacy, practice, service. That period of celibacy gave me the incredible experience of being with desire and not satisfying it. I was choosing for the cultivation of my own spiritual practice that I wasn’t going to be sexual—no masturbation, no intercourse, complete restraint. And I could really see clearly: Oh, desire arises and passes away.

—Noah Levine, “Confessions of a Dharma Punk,” Winter 2000

39. There are always obstacles to daily practice. Some are quite obvious: traveling, staying up really late, changing your schedule a lot. For the most part, I’ve found the difficult obstacles to be the ones that come from within, those mental tricks we all use—you know, it’s early, it’s cold, I can’t sit. The biggest obstacle is just the mind. You think you’ve got to get up right away and make some calls, or have breakfast, or go do this other thing. Your mind always tries to play these tricks. Things suddenly seem really urgent. For me the solution has been to create a schedule, to find myself some disciplined time, to just get up every day at seven no matter what. I’ve made a habit to get up, brush my teeth, sit—in that order—before I do anything else. And then, of course, after you sit you finish and you say to yourself, “What was so urgent that I felt I couldn’t sit?”

—Dan Rosenberg, from “Making Time to Meditate,” Spring 2001

40. There is no Buddhism that does not hold that liberation from suffering involves the elimination of desire, hatred, and ignorance, the three root kleshas, or obscuring emotions.

Now, in the Americas and in Europe, Buddhism has once again landed on alien shores, and once again this ancient wisdom tradition is having to find its place in an alien culture. But this time, the dominant cultural context that Buddhists must adapt to is neither a religious nor a political worldview. It is consumer capitalism.

—David Patt, “Who’s Zoomin’ Who? The Commodification of Buddhism in the American Marketplace,” Summer 2001

41. Generally speaking, it is better to keep one’s own tradition. It is more suitable. Bur among some people—in the West they are usually Christians, Jews, and to some extent Muslims—there is an interest in Buddhism. Sometimes, because of their individual mental dispositions, they do not find much in their own tradition that is effective, but they still want a spiritual practice. They feel a strong pull toward Buddhism, and then, of course, it is their right to follow Buddhism. After all, all religions belong to humanity. What’s important is that once we make a decision to follow another religion, we must keep in our minds that we must avoid criticizing our own previous tradition. We must show respect for it.

—”Ethics for a Secular Millennium: An Interview with the Dalai Lama,” Fall 2001

42. The attacks in New York and Washington burst my complacent Buddhist bubble. I found myself facing urgent and overwhelming questions for which broad truths of Buddhism did not seem to provide an adequate response. Is an open society that tolerates dissent even possible without its being underwritten by violence? For if dissent were to take the form of violently seizing others’ lives and property, with what resources would a nonviolent society respond? Is a sustainable human society therefore inescapably dependent on the threat of violence? And if so, is the Buddhist commitment to nonviolence but a noble aspiration whose goal can never be reached on this earth? Despite all

their talk of love and compassion, do Buddhists have the capacity and resolve to imagine and realize a truly nonviolent world? Or is nirvana, after all, the only peace we can hope for?

—Stephen Batchelor, “Spaces in the Sky,” Winter 2001

43. Yet as you begin to settle into the very particular mood that develops—that of a cabin high up on a chill mountaintop in the dark, a single light inside—you see that it is in the raggedness that the radiance can be found. There is a crack in everything, as [Leonard] Cohen (following Emerson) sings on a recent album, and that’s how the light gets in. The opening song here, “My Secret Life,” tells us, in effect what to expect—for the secret life this singer confesses to is not one of venality and deceit and ambition, but the opposite. Cohen’s secret, at this point in his life, is not that he’s fallen, but that he occasionally manages to rise above it all. The mystic’s way in every tradition is to invert the world by remaking the very terms with which it presents itself (turning its words upside down as a way to turn its values inside out); Cohen’s secret life (since he’s as impatient with the dogmas of the monastery as with those of the world) is the place where he makes love in his mind and refuses to see things in black and white.

—Pico Iyer, reviewing Leonard Cohen’s album Ten New Songs, Spring 2002

44. Now, if the practice is so good for us, why is it so difficult to maintain a steady practice? It may be that the notion that practice is “good for us” is the very impediment—we all know how we can resist what is good for us at the table, at the gym, and on the Internet. This mechanical notion of practice, “If I practice, then I will be (fill in the blank),” leads to discouragement because it is not true that practice inevitably leads to happiness or anything that we can imagine. Our lives, like the ocean, constantly change, and we will naturally face great storms and dreary lulls.

How, then, to put our minds in a space where practice is always there, whether tumultuous or in the doldrums? It requires a completely radical view of practice: Practice is not something we do; it is something we are. We are not separate from our practice, and so no matter what, our practice is present. An ocean swimmer is loose and flows with the current and moves through the tide. When tossed upside down in the surf, unable to discern which way is up and which way is down, the natural swimmer just lets go, breathing out, and follows the bubbles to the surfice.

—Sensei Pat Enkyo O’Hara, “Like a Dragon in Water,” Summer 2002

45. As we observe sensations without reacting to them, the impurities of our minds lose their strength and cannot overpower us.

The Buddha was not merely giving sermons; he was offering a technique to help people reach a state in which the could feel the harm they do to themselves. Once we see this, sila, or ethics, follows naturally. Just as we pull our hand from a flame, we step back from harming ourselves and others.

It is a wonderful discovery that by observing physical sensations on the body, we can eradicate the roots of the defilements of mind.

—S.N. Goenka, “Finding Sense in Sensation,” Fall 2002

46. People can complain about “Buddhism lite,” but I trust the practice. I have a lot of faith in people’s hearts. I believe that inherent in each person is a momentum toward liberation and greater compassion. And if you help people in appropriate ways, that’s what wants to come out. I don’t have to proselytize or encourage people to move in any particular direction. It’s best just to meet people where they are. If practice is too self-centered, sooner or later they will either stop practicing or understand the limitations of being self-centered. After a certain point, it is not possible to continue practicing just for yourself. The motivation to keep going comes in part from caring for others, also.

—“Living Two Traditions: An Interview with Gil Fronsdal,” Winter 2002

47. And yet, in the situation we find ourselves in today, doesn’t it come to us naturally that it’s in our self-interest to extend compassion to those beyond our local groups? No, it doesn’t. Because to worry about what some disenchanted Muslim teenager in Pakistan is feeling right now does not come naturally in the sense of visceral response. It does, however, make intellectual sense; the world is moving to a point where, if only out of self-interest, we need to think about that person. One virtue of some of the religious traditions is that they have well-worked-out procedures for assisting this intellectual process. In other words, it’s one thing to realize logically that my fate is intertwined with the fate of Muslims around the world: If they’re unhappy, they’ll eventually make me unhappy. But it’s another to feel it, to look at someone and get a deep sense of fraternity with them. That’s where religious practice plays an important role. In Buddhism there ismetta meditation, in which we cultivate compassion for all sentient beings. This sort of practice is what I would consider a product of cultural evolution.

—”Darwin and the Buddha: Tricycle Interviews Robert Wright,” Spring 2003

48. Wherever we are, whatever we’re doing, what we need to acknowledge is something natural. Something uncontrived. The uncontrived state is actually very special. Being natural is very special. And this natural way is actually already with us, in or out of retreat, but we just don’t acknowledge it. If you just acknowledge your natural way, that’s enough, good enough. It’s like the cow peeing in the field {laughs}. It just stands there and pees. Every day, it just pees, quite naturally. That’s really enough.

—”The Easy Mind: An Interview with Mingyur Rinpoche,” Summer 2003

49. I think skepticism is very admirable, and rather unusual. The history of the world reveals that people are drawn to those who provide a strong, uncompromising teaching. We’re drawn to those who say, “This is it, and everyone else is wrong.” Certainly we see this pattern in contemporary politics, but we also see abuse of this sort within spiritual circles. It makes you wonder: Do we really want freedom? Can we handle the responsibility? Or would we just prefer to have an impressive teacher, someone who can give us the answers and do the hard work for us?

—Larry Rosenberg, “The Right to Ask Questions,” Fall 2003

50.