Noah Levine, born in 1971 in Garberville, California, began dharma practice while institutionalized—having been arrested for drugs and violence—in Santa Cruz County Juvenile Hall in 1988. He has been practicing since then, primarily in the Theravada tradition. The son of Patty Washko, and of Stephen and Ondrea Levine who are dharma teachers and pioneers in the field of conscious dying, Noah directs the Spirit Rock Teen and Family Program in Woodacre, California. For the last several years, he has been teaching meditation in juvenile halls and prisons. The following notes were compiled from a conversation with Tricycle in New York City.

Some people my age come to the dharma with a peace and love attitude, a hopeful perspective. But there’s a whole range of culture or backgrounds—even within our generation. There are those of us who grew up in the seventies and eighties who thought that the hippie movement didn’t work, that they kind of just sold out and became yuppies and didn’t really follow through on their intentions. So in response there was this whole punk rock movement, a more aggressive, less peaceful and loving approach.

There was a whole generation of punk rockers saying, “We realize that we’re being lied to, that this is all a sham, the American dream, that the Western world is lying to us about what the nature of happiness is.” This attitude was being expressed in violence and in fashions and attitudes, even in livelihoods—this feeling that we won’t participate in the system like our parents’ generation did.

I went through a teenage rebellion, rebellion against society, against the system, against my parents. I was very deeply identified with the punk rock scene—anti-establishment, anti-authority, anti-peace and love. I wasn’t sure what life was all about but I was sure that I was being lied to. At sixteen I left home. I said I had enough of my parents’ rules and I left New Mexico, I dropped out of school. Stephen and Ondrea were basically saying: “If you continue to act this way, you’re gonna get yourself into a lot of trouble, you’re responsible for your own actions.” This teaching that actions have consequences went right over my head, and I hit the road.

There I was, this sixteen-year-old punk—Mohawk, leather jacket, studs, boots—on the streets. Within two weeks of leaving home I was arrested for public intoxication and assault and battery—I had hit someone with my skateboard. As a teen, I became entirely addicted to booze and drugs and sex and violence and external stimuli.

I was looking for happiness through entirely unskillful means, got myself into a ton of trouble and was institutionalized off and on for many years for crimes having to do with stealing and drugs and violence, mostly stealing to support my habit. I started smoking pot and drinking at a very early age. In my early teens I was eating lots of hallucinogens—doing acid and mushrooms. By the time I was in high school, or should have been, I was doing PCP and crack and heroin and any kind of pills that I could get my hands on. At sixteen or seventeen I was completely strung out. And so I was sent to juvenile hall, to group homes, diversion and drug programs, counseling, probation, all that stuff.

When I was seventeen years old, sitting in juvenile hall, two things happened. First, while I was on the phone with my father—complaining about all of the fear of what was going to happen at court next week, and the regret and remorse for what I had done—he offered me anapanasati, mindfulness meditation instructions. Using those instructions, I began, for the first time, to really look inward. I became aware of my breathing, counting my breath, breathing in one, breathing out two, and realizing, “Wow, in this moment I can actually just be with this breath and not have to worry about the future and the past.” It was a revelation for me, because I was spending all of my time in fear of the future, pushed and pulled by my thoughts and feelings.

I had this real opening in my cell and began what has turned out to be a twelve-year meditation practice.

Another critical thing that happened during that time was I was introduced to the twelve-step program. I realized that I was actually addicted to the booze and dope and I started on the path of recovery. The first couple of years I wasn’t really doing the steps, I was just going to meetings and doing sitting meditation once in a while and still really looking for happiness outside myself. I did have that “Aha!” experience when I realized: Okay, it’s not drugs and alcohol, I’m not gonna find it there. But I wasn’t sure—maybe I’ll find it in sex, maybe I’ll find it in stuff, maybe I’ll find it in getting attention and continue into sort of being violent and the sort of street punk that I was. But I was sitting a little bit here and there when it got bad enough. Two years into recovery, I was in a ton of trouble for doing graffiti, for stealing, for fighting. I had everything I wanted—I got the apartment, the girlfriend, the car and the motorcycle—all that stuff that I thought would make me happy, and I was still feeling empty.

I got busted for doing spray paint, for doing graffiti, serious trouble in California. They wanted to put me in prison—$20,000 worth of damage.

I was told I could go to prison for seventeen years. They were trying to make an example of me. But it brought me to practice, it gave me that second “Aha!”—Okay, it’s not drugs and alcohol, it’s not sex, it’s not money, it’s not any of that stuff, it’s not attention, it’s not the motorcycle, it’s not being with somebody, it’s not the ego trip.

I had seen people in the twelve-step programs and in the spiritual community, the Buddhist community, find happiness, but it wasn’t happening for me in just not drinking, just not using. And so that was a turning point for me. I got a sponsor and started working through the steps and simultaneously started sitting retreats. I sat my first retreat in ’91 with Jack Kornfield and Mary Orr, and right away it was like, “Oh, this is what I was looking for, this is where the freedom is, in this moment, in this breath, in this retreat practice, in the Buddha-dharma.”

So I started sitting retreats and I started working with the steps, and it was really simultaneous. I eventually took a two-year vow of celibacy when I was twenty—in my prime!—[laughs] and went from being an indulgent addict to the other side: celibacy, practice, service. That period of celibacy gave me the incredible experience of being with desire and not satisfying it. I was choosing for the cultivation of my own spiritual practice that I wasn’t going to be sexual—no masturbation, no intercourse, complete restraint. And I could really see clearly: Oh, desire arises and it passes away.

I started to ask: How can I use my suffering, my life’s energy to benefit others? How can I be of service, not only to people in recovery but to everyone? I started working in the medical field. I thought, Well, maybe I’ll be a paramedic or a nurse or a doctor—that’s a good way to help. As I worked through the twelve steps and made amends to all of the people I had stolen from or fought with and offended in any way—I went out to hundreds of people directly asking for forgiveness, did that in the twelve-step program while simultaneously doing forgiveness practice in the Buddhist traditions—I started finding this freedom through the practice and realized, Oh my God, I can actually be comfortable in my own body! I can actually be happy and not be filled with fear all of the time or run around by aversion or grasping.

I think that the work that is most inspirational and important to me right now is with young adults, with people in their twenties and thirties, people of my generation—being able to share the dharma and the practice and offer instructions to my peer group. It just feels like a really wonderful use of this precious gift that I’ve been given.

To have the good fortune to hear the dharma and practice it, and then being able to say, “Check this out, try this,” and to share it with others has been incredibly important to me. In my experience, there are definitely some people in their twenties and thirties who are interested and often very committed to practicing Buddha-dharma, but it’s a minority of my generation that is represented at dharma centers, certainly the ones that I’m familiar with anyway.

I know from the sitting groups that I go to, from the retreats that I sit, from the conferences and teachings that I attend, that the sangha appears overwhelmingly gray. I think that one of the reasons that the Zen and Tibetan and Vipassana communities were flourishing in the sixties and seventies, and attracting crowds of young people, was that almost all the teachers were of the same generation as their students. Jack Kornfield, Joseph Goldstein, Sharon Salzberg, Trungpa, Ram Dass, all of them. It was not cross-generational teaching like it is now. It is a much different experience when a nineteen-year-old comes into a dharma scene now and their teacher is sixty and this teacher is wearing a tie and driving a new car. So the teachers are scratching their heads and wondering “Where’s the next generation?” Other than some young reincarnated lamas, there are no people of my generation teaching the dharma. As the teachers have aged, so too has the sangha.

People complain, too, that it’s expensive to practice, although that’s not my experience. I’ve sat retreats for free, I’ve applied for scholarships, I’ve done what I wanted to because I was highly, highly motivated to do it. But still, it is not as accessible as it could be. It’s not easily accessible, and it’s also not attractive to young people because there are so few people of their age in the sangha. I practiced for ten years with a sangha where I was one of the only young people.

As far as teaching goes, it certainly helps to have grown up in a dharma family and have a famous dad for a teacher; I’m sure it opens a lot of doors for me. But, as Stephen [Levine] has said, that will get you invited in for tea and that’s about it. If you don’t have something to offer, you won’t be asked to stay. It’s an interesting karmic situation for me to be in, and it is sometimes quite challenging to have such high teachers for parents, in my mind. I’ve been encouraged by Stephen and Ondrea to teach from where I’m at, to stick to what I know to be true and have experienced firsthand.

Stephen and Ondrea are the main teacher figures in my life, although it’s a tricky relationship because they are both parents and mentors. I also work with Howard Cohn and Eugene Cash from Spirit Rock Meditation Center. I feel that all of the Spirit Rock teachers have mentored me in some way over my period of employment there, whether by example, offering inspiration, or teaching together. I use the word mentor because I feel that they are not only my dharma teachers but also my mentors in becoming a teacher-in-training. I feel that there is some separation between coming just for meditation instructions and dharma teachings and actually looking for some guidance in how to teach the dharma. I consider them my mentors in the path of dharma teaching.

I think it would be entirely helpful if teachers were more willing to really train some of the next generation that are coming around. Of course, there need to be some parameters around it. After practicing for a couple of years, you’re not really ready to begin teaching, and that it has to be maybe ten years of practice or something. I’m wondering how come it’s not happening yet. Is it because there are not many people are in their twenties and thirties that have been practicing for ten years? I know five—that’s about it. But I’m sure there are more of us out there.

One of the things that we see in our community—and I think that you can even apply it to all of America—is a real lack of any kind of rite of passage, of any kind of transition from childhood into adulthood, or even just from childhood into teen. At Spirit Rock we’re beginning a rites of passage program. It’s something like the Buddhist’s answer to the Bar or Bat Mitzvah. We have been incorporating Native American traditions into the teen program. We do a vision quest for teens, where they actually do a lead-up series of practices, a 6-week introduction to the tradition and the practice, about what to do with afflictive emotions, strong feelings, fear—fear that animals may come after them, or that hunger will arise—the mind in all of its unraveling. And then they spend several days alone.

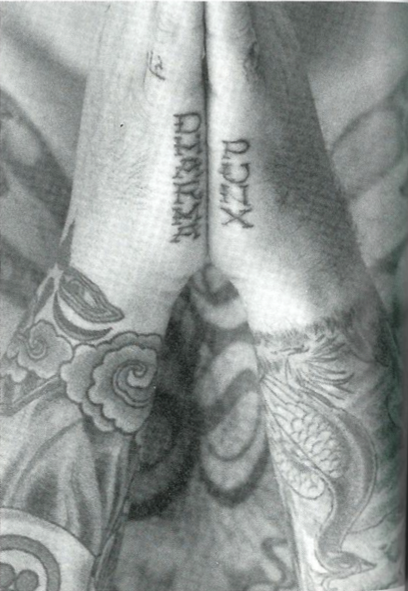

It’s just incredible, I mean they get the opportunity to practice what the Buddha taught. They’re sitting under a tree alone in the forest for two days—you know, at fourteen, fifteen, sixteen. They’re watching their minds, watching their own nature. They’re fasting—no food or water. And as we create this rite of passage we are reminded that there hasn’t been an American rite of passage, other than sex and violence and drugs. In my own case, getting tattooed was probably some form of a rite of passage. Maybe it’s just an ego trip. I mean, I feel like there’s something within me that wants to be expressed in that way. What does it give me? Attention. Sometimes it’s fun, sometimes it’s a real nuisance.

Is there anything really deeply spiritual or psychological behind it? I don’t know. It’s something that remains within me, you know, a desire to be tattooed. It does set me apart from the mainstream—the mindless, sleeping American culture that I so disdain, that I have so much aversion to. And there’s probably also some stuff around being a white male. I don’t really identify with the power dynamic of being a white male in white male America. So being heavily tattooed sets me apart from that, which I enjoy, you know, not being identified with The Man.

Also it’s a constant reminder, I look at my arms: Oh Buddha, Oh Krishna, Oh Om…Ah, transformation, practice, compassion and wisdom. Yet being tattooed is motivated by greed and hatred and delusions [laughs]—you know, it’s quite a contradiction, isn’t it? Even though I am still a novice, only ten years into the practice, the amount of freedom and happiness that I feel, and genuine compassion—it’s incredible, it’s almost overwhelming to me sometimes.

My question is, coming from the depths of addiction, violence, greed, hatred and delusion, have I just finally attained a normal state of mind? Am I mistaking this happiness for some spiritual experience because I came from such a depth? It seems incredible, that one can be comfortable, can be happy, can experience satisfaction in moments.

I’m not claiming to have any kind of high spiritual experience, but a tremendous amount of freedom is present moment to moment that I can share with others. It’s a great question because I can see how people have these experiences and then all of a sudden they’re like, Oh, I’m awake! Am I awake, or am I just finally at sort of a human level, when I spent all of this time in the hell realms and the animal realms? And now there are these moments of the bliss realms, of this kind of heavenly abode, and it’s probably more like, Oh, finally I’m in this human realm and there are moments of hell and there are moments of heaven, but mostly it’s just sort of—this.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.