I have covered my badge with black tape so it will not reflect the light. The January midnight air is colder than the gun in my hand, a .357-caliber Magnum revolver, made of blued steel, so it won’t reflect light. It has etched wooden handles so it won’t slip.

I have covered my badge with black tape so it will not reflect the light. The January midnight air is colder than the gun in my hand, a .357-caliber Magnum revolver, made of blued steel, so it won’t reflect light. It has etched wooden handles so it won’t slip.

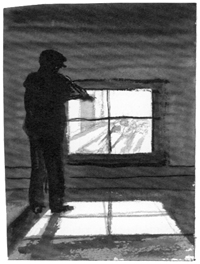

I am standing silently outside the basement window of a home on the San Francisco peninsula. I am focused completely on the three people inside, lying on the bed directly below the window. The window is partly open. The room is brightly lit. How can they sleep in that bright light? Are they asleep? The smallest one is only a month old. She lies between her father and mother, who are both fully clothed, both very young themselves. Far too young for the trouble they have brought upon themselves, and the threat they are now bringing to their child.

My gun is perfectly silent in its aim at the head of the young man. He can’t be asleep in all that bright light. He knows. He is vigilant. So am I.

A light knock at the door of the basement bedroom. An older woman’s voice. I hope they move her out of the way so she will not have to see the most horrible potential outcome of this situation. “Yeah, Mom, what is it?” “Stephen, come on out here; I want to talk to you.” “No, Mom. Later.” “Now, Stephen.”

He knows. He is vigilant. His hand is under his pillow. He has a gun. And he is not moving. That is good. His wife and child do not move either. With a sharp slamming explosion the bedroom door is splintered. Three dark figures aiming automatic weapons burst into the room and hold off all movement with the aim of the guns. I see slight movement in the shoulder of the young man. It is the hand under the pillow.

“FREEZE!” He looks up at me. He freezes. At the direction of the three police officers, the wife peels herself slowly off the bed. The grandmother moves to pick up the infant, and an officer stops her. Ever so slowly the young man is directed to remove his hand from under the pillow. It had better be empty. It is. He and his wife are handcuffed. I replace my weapon in the holster. Thankfully, the revolver continues to be cold. The pillow is removed, and there is the semi-automatic pistol. I move from the window, into the house, into the room. The narcotics officers undiaper the infant. There, in the diaper, is an ounce of heroin.

“FREEZE!” He looks up at me. He freezes. At the direction of the three police officers, the wife peels herself slowly off the bed. The grandmother moves to pick up the infant, and an officer stops her. Ever so slowly the young man is directed to remove his hand from under the pillow. It had better be empty. It is. He and his wife are handcuffed. I replace my weapon in the holster. Thankfully, the revolver continues to be cold. The pillow is removed, and there is the semi-automatic pistol. I move from the window, into the house, into the room. The narcotics officers undiaper the infant. There, in the diaper, is an ounce of heroin.

For thirteen years I was a law enforcement officer. In the dark humor of that environment, we called ourselves “paid killers for the county.” No one else wanted to be in our boots. I did not identify myself as a Buddhist; I was not aware that the way I behaved and experienced the world fit squarely with Buddha’s teachings. It is clear to me now that we could have been, and were, instruments of karma. But skillful action, discriminating awareness, karma, the law of causality were not terms used in law enforcement basic training.

For a Buddhist in police work, the most important thing is to be constantly aware of ego. It is not your anger, not your revenge, not your judgment, no matter how personal the event. I was paid and trained to take spirit-bruising abuse. I endured things of which the majority of women in America will never even dream. For me it was not judgment, in the Western sense, but discernment. This kept me, and others, alive and healthy. This discernment allowed me to act skillfully in crisis. The law of causality allowed me to know that if I could not stop the perpetrator of violence or pain or loss, that some other vehicle would reach that person-karma.

The law of causality also applied to me, of course. I never questioned that what I did in law enforcement, under all circumstances, had to be the best thing I could do, producing the least harm, even to the criminal. Of course I was not pure; I lost my temper, and I can remember the individual times I crossed the line. But my line was so much more sensitive than those of some of my co-workers.

Compassion. How many times did I “arrest” a person, or accept a person into the jail, who was only a victim? Poverty, mental illness, abuse. In this way I could give them warm food, a place to sleep for a few hours, clean clothes, a shower, and possibly a referral or evaluation for future monitoring. When they left, for some period of time, they were healthy members of the community. And no, they did not return regularly for a “handout.” Jail is not that kind of place. Quite often, I was guilty of the sin of having little compassion for myself, and sometimes, of stretching the rules to offer comfort, to soothe the pain caused by other necessary actions. The tools of my venturing out to find that justice included attitude and presence, voice, my brother and sister cops, physical restraint techniques, mace, a baton, a handgun, and a shotgun. There was an escalation of use appropriate to the actions of the violator. One did not draw a gun without a direct physical threat to the life of a human being.

Compassion. How many times did I “arrest” a person, or accept a person into the jail, who was only a victim? Poverty, mental illness, abuse. In this way I could give them warm food, a place to sleep for a few hours, clean clothes, a shower, and possibly a referral or evaluation for future monitoring. When they left, for some period of time, they were healthy members of the community. And no, they did not return regularly for a “handout.” Jail is not that kind of place. Quite often, I was guilty of the sin of having little compassion for myself, and sometimes, of stretching the rules to offer comfort, to soothe the pain caused by other necessary actions. The tools of my venturing out to find that justice included attitude and presence, voice, my brother and sister cops, physical restraint techniques, mace, a baton, a handgun, and a shotgun. There was an escalation of use appropriate to the actions of the violator. One did not draw a gun without a direct physical threat to the life of a human being.

It is true that the sound of “racking in,” a shotgun round to the firing chamber of be weapon, has a significant, positive, controlling effect on people out of control. An alternative use of the weapon. I did not draw a gun without being entirely prepared to use it. There were at least four times that I made the decision to kill someone. Luckily, their actions deterred that decision. Hands were empty; they turned another way; they let someone go; they dropped their weapons.

Blessings. Don’t let any of this make you think that I was easy on anyone, or that I was always in control. Back in the beginning, without the understandings that have come to me during and since police work, I was lost to some of the pain involved in that work. I drank. I wasn’t an alcoholic, but drinking was a way to commune with others in pain, and to dull it for the moment. Enough to sleep and to go out and face it again the next day. Just take the edge off. And never on duty or when duty was imminent. Harm. When you are sick, and the doctor gives you a shot of antibiotics, it hurts, but the intent is purely to mitigate the harm of the infection. So, hurt and harm can be two different things. Prying clinging, screaming children, covered with bruises and cigarette bums from their mother, hurt all of us. Photographing the scene of the stabbing of an elderly woman hurt. Arresting a heroin addict who would then have to go through withdrawal was painful to the addict, and irritating to the staff. My actions were more often than not to mitigate harm in the longer run. The greatest pain occurred with the clarity of the truth: you committed the crime; you will pay the price, one way or another. Often the price paid under corporeal law was far less than that paid under cosmic law.

There were other kinds of pain. Painful to have to follow orders from supervisors who questioned your every move because you are a woman. Painful when the law allowed for the release of an attacker, or a child abuser, or major drug dealer. I just had to take refuge in knowing it was not over for them. But how much harm, how many lessons like mad bees into the world, would they cause before it all caught up with them? And what of their ignorance and pain?

Other pain. Being attacked by a totally crazed woman twice my size hurt. And I was angry and in pain for days. The appropriate action, after others helped pull her from me and before my visit to the emergency room, was to charge her with assaulting an officer-a felony. I did this. It did not relieve my physical or mental pain from the attack; it was just procedure. I took a very little bit of solace from the fact that it was not me she was attacking, but the uniform that terrified her and represented confinement. And some solace in my belief that she needed to be removed from the community and treated to relieve some of her own pain. Western society is not really very good at that yet.

I have heard the mad bees, small lumps of lead flying past my head at 1,138 feet per second. I have been in someone else’s blood up to my wrists. I have plugged the gunshot wound-a sucking hole-in a drug dealer’s chest, to have him laugh at me in court. I have chosen to kill, should it be warranted. And I woke one day knowing my tour of duty in the charnel ground was over. I turned in my badge and revolver, but not the lessons, not the images.

These days I am vigilant in other ways, and not so blatantly the instrument of karma. In this society there is a constant effort to clean up and disguise the charnel ground events around us. This robs us of opportunity. I did a lot of cleaning up: covering tom skin and broken bones, housing and feeding the disoriented, offering evidence to remove the criminal from the neighborhoods. I lost my hope for comfort in the world. But I am not hopeless; I anticipate, and I am more quietly vigilant.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.