In the late seventies and early eighties, I would escape every few months from my political work in Jimmy Carter’s White House to play chess with my old friend and Buddhist teacher, Geshe Wangyal, in Washington, New Jersey. From dawn till night the long silences, laughs, and wild accusations of cheating could be heard throughout the house. Meditative serenity sought by those looking for the “Wisdom of the East” was hard to find in his retreat center.

Like many of my generation, I had been lucky enough to sojourn in the psychedelic renaissance of the sixties. We had returned from our travels convinced that something fantastic lay beyond the reality of here and now. We believed that satori, the flash of enlightenment—Buddhist, Hindu, Judaic, Islamic, or Christian—was an intense, orgasmic experience, and we searched for the path that would lead permanently through the doorway of this tarnished, ordinary reality to the white light of absolute enlightenment.

In 1971, I came to Geshe Wangyal from Harvard to escape the corruptions and compromises of the twentieth century, arriving on his doorstep macrobiotic, otherworldly, intoxicated by my rarefied notions of emptiness, and certain that he held a key. I was ready for meditation, study, and Zen asceticism. I wanted to be a monk.

But he shaved my beard, not my head, stuffed me full of boiled lamb fat and, after a few months of chess and construction work, tossed me back into the twentieth century, insisting that the door to enlightenment was to be found in the very stuff of ordinary reality. His mantra was not just to say “om mani padme hum” but to do something useful.

Over our games of chess, he coaxed me into politics. Compliant, I followed his advice and over the last twenty years have searched for the doorway in Carter’s Washington, Noriega’s Panama, Shagari’s Nigeria, Papandreou’s Greece, Donald Manes’ and Ed Koch’s New York City, Marcos’ Philippines, Chung’s Korea, Li Peng’s China, and the Cartel’s Colombia.

More often than not I lost track of which were the white and black pieces. I often found the game with the darker players, the black pieces, to be more engaging, seductive, and even more honest than that with the sometimes pious, precious, and self-proclaimed forces of good. But in moments of confusion, I often wondered who this monk was and why I trusted him so completely.

Wangyal was a Russian Kalmuk, born in 1901 under the Czar’s rule. He grew up in a nomad’s yurt on the steppes near the Caspian Sea and became a monk at an early age under the tutelage of Lama Dorjieff, one of the most intriguing and charismatic characters of modern central Asia.

At Drepung monastery outside of Lhasa, Wangyal earned his “Geshe” title—the Tibetan equivalent of a doctorate in Buddhist philosophy—after fleeing the Russian Civil War. A great scholar, he became a well-known character in Lhasa. He had the best horses, carried two pistols in his robes to ward off horse thieves and robbers, loved to gamble at dice, played chess, lived well, and maintained a fervent love for his Buddhist studies.

Traveling extensively, he tasted the richness of life in Peking and loved Chinese clothes and cooking. With the English diplomat, Sir Charles Bell, he visited Japan’s Manchuria, then witnessed the rape and looting of China. In London, sporting a bowler hat and monk’s robes, he walked through the twilight splendor of the British empire but was never blind to its social inequities. He witnessed the birth of modern India and foresaw Mao’s killing fields. He enjoyed the last days of freedom in Lhasa before Tibet, too, was crushed.

In 1955, Time magazine announced Geshe Wangyal’s arrival in New York from India. In the 1950s and 1960s, the CIA assisted the Tibetan resistance against the Chinese, supplying limited training and military support to small, courageous bands of border fighters. Politics, religion, philosophy, and daily life were all integrated into a coherent, nondual practice. For Geshe-la, (“la” is a Tibetan term of endearment), there was no contradiction between teaching Tibetan language and philosophy one day, and on the next, going to Washington to work for the CIA’s half-hearted campaign which was not so much for the Tibetans as against the Chinese. Only later did the Tibetans learn that they were an expendable pawn in Henry Kissinger’s flawed realpolitik.

Determined to bring the Buddha’s teachings to America, he set out to teach a few hand-picked students, some of whom, such as Robert Thurman and Jeffrey Hopkins, were later to become prominent American scholars of Gelugpa Tibetan Buddhism. Later, his work was recognized by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who spoke of him as one of the great founders of dharma in the West.

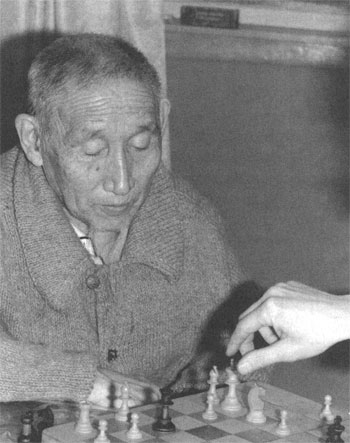

By the time I met him, Geshe Wangyal was an old, androgynous monk, at times loving and wise, and at others, wrathful and cunning. His goatee had a few long, white strands, his skin was yellow and wizened and his eyes were piercing and delighted, but sometimes fierce and intimidating.

Hiding himself in ordinariness, he lived ecstatically in suburban, bourgeois New Jersey, sewed and washed his own clothes, grew his own vegetables, and tended his flower garden with the same love he gave his students. He loved shopping centers, enjoyed haggling at the local farmers’ market, watched “The Lawrence Welk Show,” worshipped the American flag and the anti-communism it represented, and proudly constructed a house with the most atrocious mix of synthetic building materials. He put aluminum siding on his ceilings and thought it surpassed the architectural perfection of Kyoto’s Nanzenji.

Chess was his addiction; played with a strange variation of Mongolian conventions inherited from his nomadic ancestors, who would sometimes stake all their tribal possessions on the outcome of a game. Occasionally he would look up from the board to enjoy a quick slurp of his heavily salted and buttered tea or to steal a sadistic glimpse of his panic-stricken foe. He trusted no one—especially in a game of chess—saints, incarnated Tibetan lamas, respected university scholars, or supposedly loyal disciples.

Late at night, when the saner members of his household had gone to bed or retreated to their religious studies, Geshe Wangyal would talk to me about world history, the universal decline of Buddhism, the dilemmas of religion and politics, and the trials of his own life. But his discourses would never interfere with his aggressive pawn attacks on my wobbling defense.

He believed the history of this century had immense religious significance. Each detail of life in New Jersey, each word of Walter Cronkite’s evening news, he saw as a vital part of our collective struggle to become conscious, to fight the forces of ignorance, hatred, and desire within us, to end suffering, and to achieve enlightenment for all sentient beings. His life had taught him that the realities of politics must be an integral part of the modern Buddhist path, for in this age of the Kaliyuga, the cosmic age of destruction, there is no such thing as “dropping out.” Mao’s and Deng’s brutal destruction of Tibet taught him that there is no place to retreat. The yogis and mahasiddhas of our day will have to practice their enlightenment in the suburbs of New Jersey or the rubble of Beirut. His lesson was that a separation between politics and religion was a fatal error.

To Geshe-la’s mind, the sangha—the worldwide family of Buddhism—had grown too intoxicated with the delights of abstract philosophy and meditation. The heirs of Buddhist dharma in the East had become effete and self-absorbed. They had forgotten their obligation to use their wisdom for others, to protect people, especially their neighbors and families, from the horrors of the modern totalitarian state.

This failure of modern Buddhist practitioners has led to a worldwide Buddhist holocaust. In 1945, Buddhism was the largest religion in the world. Today it struggles to survive in North Korea, China, Tibet, Inner and Outer Mongolia, Russia, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and now Burma.

Geshe-la insisted that American Buddhism avoid this error of self-absorption and pious detachment from the world. He was determined that American Buddhism be grounded in present-day reality, convinced that Buddhists must be politically involved.

Unlike chess, however, politics is not a world of black and white, but varying tones of grey. Yet one’s ignorance, desire, and anger find it easy to grow in a grey culture. Almost anything can be rationalized. This is why the game is so dangerous.

For example, in my political consulting work in Panama during the eighties, I was asked by the most practical forces of reform to work with General Noriega in order to entice his military troops peacefully back into the barracks. If we had been successful, it would have been the most constructive and peaceful solution for all—“the Brazilian military solution.” The alternative has been a nightmare.

Later I found it easier and morally safer, but less effective, to work overtly with the righteous opposition. I helped bring Noriega down, but on the day of the U.S. military invasion in 1989, I knew I had failed. As the U.S. paratroopers dropped into Panama and fought men who had once been my friends, I began a new life while dancing in Atlantic City to Mick Jagger singing “Midnight Rambler.” Perhaps Geshe Wangyal would have stayed longer in the heart of darkness and lived next to Noriega—worked from within—not caring what others might have thought.

Wandering through the Alice in Wonderland of international politics where so many governments and well-meaning people are checkmated by their own conflicting motivations and desires, I have now learned the most basic lesson of Buddhism and see how incredibly difficult it is to practice: good motivation.

Geshe Wangyal taught this yoga to me with chess, when he would stalk, tempt, and taunt me until I was cornered and humiliated. When trapped time and again, that ambitious, fiercely competitive, self-cherishing part of me would manifest and explode. At those moments Geshe-la appeared to me to be more like Kang Sheng, Mao’s murderous secret police director, than like Manjusri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom.

With a contented chuckle at having conjured up my ugliest emotions, he would note that the fuming devil across the board from him was in fact the very object of play in Buddhist philosophy—it was the “object of negation” I had so antiseptically been studying. He would then ask, with a mockingly compassionate tone, if my current incarnation felt impermanent, interdependent, empty, and blissful. And of course, it did not. It wanted to kill, smash, and humiliate this Kalmuk trickster.

Now, without my old friend’s laughs and taunts, the game can often seem hopeless, and retreat so enticing. But I also remember the core teaching of this old shaman: effort, which is the fourth of the six paramitas or perfections. He taught this paramita with the game. Never give up. Be determined to play game after game—infinitely. As soon as one meets defeat, no matter how total, rise up and challenge the “magician’s illusion” to yet another game, for enlightenment is the playing. He taught this lesson to his death.

Ten days before Geshe Wangyal died of liver cancer in 1986, I awoke mysteriously in Palm Beach, Florida, after a delirious night of drinking with my cohorts in New York’s 21 Club. On waking, I vaguely remembered that my old friend was staying the winter at a small house nearby.

To my surprise, I found him ill and near death. I had lost touch with him over the last year or two. His eyes were yellow. He could hardly move. Preparing for his death with total concentration, he was chanting the same morning prayers he had recited for over three-quarters of a century.

Geshe-la and I sat alone in silence. He grabbed my hand, and I wept. I tried to cheer him up and awkwardly suggested a game of chess, thinking that I would throw this last contest to bolster the spirits of a sick, feeble friend. He immediately livened up.

After being helped to the edge of the battlefield, Geshe Wangyal took up his position and began pushing his king’s pawn to K4. We played deliberately at first, but the pace soon quickened, and he pushed his pawns without mercy.

He surprised me. I fought back, quickly dropping any compassionate interest in cheering him up. We were in the fight of our lives, our final game. And I was in trouble.

He crushed me, totally humiliated me. My wounded ego erupted. I was angry, disgusted at having been tricked again by this fool. He rose up in his chair and with clenched fists roared his lion’s roar: “Do you see? Do you see now who I am?”

For the first time, I kissed his feet. Jumping up, I said my farewells and rushed out the door. Weeping, I drove back over the bridge to the other shore, to the glitter of Palm Beach—and to the next game.

♦

Read more about Geshe Wangyal in “From Russia with Love: The untold story of how Tibetan Buddhism first came to America,” in the Winter 2013 issue, or tune into Tricycle Talks for an episode on Geshe Wangyal: America’s First Lama.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.