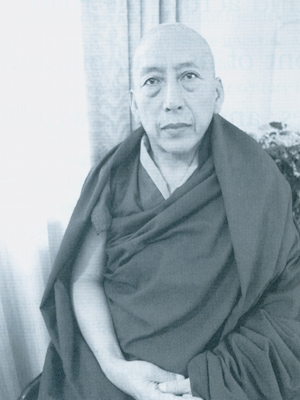

On September 5, 2001, monk, scholar, and political figure Samdhong Rinpoche became the first democratically elected chairman of the Tibetan Cabinet-in-Exile. He polled more than 85 percent of the total votes cast by Tibetans around the world. Born in 1939 in Jol village in the eastern Tibetan province of Kham, Samdhong Rinpoche fled Chinese-occupied Tibet in 1959. He lives in Dharamsala, India, the seat of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile. He was interviewed in early July by Tricycle editor-in-chief James Shaheen during a visit to New York City.

As the first elected leader of the Tibetan Cabinet-in-Exile, what challenges do you face?

The development of democratic institutions takes time, as does the development of a democratic culture. Given our situation, both are difficult. First, we Tibetans are not in our own land, and so we cannot function fully within political institutions or systems of our own making. As refugees we must operate under the laws of foreign nations. Second, our fledgling democracy was imposed by His Holiness the Dalai Lama upon the Tibetan Government-in-Exile; it was not the result of a grassroots effort. Within Tibet, the Dalai Lama is still looked to as the sole legitimate leader of the Tibetan people. But over the past twenty years many people who were reluctant to change have come around to the Dalai Lama’s view on the necessity of democratic institutions.

Are you satisfied with your progress in establishing a democratic form of government thus far?

Absolutely. What we have accomplished within the short period of forty years is remarkable. We are now functioning under the democratically adopted Charter for the Tibetan Government-in-Exile. Among other things, the Charter provides for the separation of power among the judicial, legislative, and executive branches, ensuring checks and balances. Of course, we make a lot of mistakes along the way; it’s a work in progress. But by and large, we have come a long way in setting up stable institutions. So that is good, and I am satisfied with what we’ve done up to now, especially when I consider what we have managed under the pressures of exile.

What is His Holiness’s role in your government?

Without him, none of this could have been possible. It is largely his doing. With regard to his role in government, His Holiness’s functions and powers are addressed within the Charter. For instance—and at His Holiness’s insistence—the Parliament has the ability to limit his power or to remove it altogether. In accordance with the Charter, the elected parliament wields all power.

The democracy that you are describing sounds like it’s based on the Western parliamentary model. Is that correct?

Our model is significantly different from the Western model. We want to build a Buddhist democracy. Tibetan institutions may have been inconsistent with democracy in the past, but democracy and Buddhism are wholly compatible. In Buddhism there is always room for discussion. The Buddha himself said you do not accept something just because the Buddha has said it. You accept it through examination and through analysis. If you are convinced, you accept it; if not, you continue to investigate and question. So you see, Buddhism is profoundly democratic; it is fundamentally so, relying as heavily as it does on the individual’s own experience of things.

Do you hold the same view of separation of religion and state that a Western democracy does?

In the West you speak of separation between church and state. By church you mean the institution, and for historical reasons, you have removed the religious institutions from the equation of government. But from my point of view, it would make no sense to separate the dharma—also translated as “the law”—from government. But understand that I am using the word dharma, not religion. If there is any law, then that law itself is dharma. The dharma can never be separated from the state. It can never be separated from the society. So, while separation of church and state is understandable, separation between dharma and state is not.

There may be different and opposing views of dharma. There are different Buddhist lineages, and there is a Muslim population. Will there be an attempt to separate sectarianism from the institutions of government?

Yes, and this is already the case. In fact, His Holiness always talks about a secular approach. In the Tibetan language, the word we use for secularism, chos-lyuk-rigme, means “equal respect for every religion.” If that is considered to be secularism, then we have been secular right from the beginning. At the time of the Fifth Dalai Lama, chos-lyuk-rigme was given high priority. The rights of the tiny Tibetan Muslim minority were fully protected; Muslims were given a place for a burial ground, and provision was made for establishment of mosques. So religious tolerance is not new to Tibet. If tolerance is considered to be the secular ideal, then we are secular. But if you interpret secularism as anti-religion or anti-dharma, then of course we are not. Much to the contrary: our charter states that “all the ethical and moral values taught by moral religions must be the guidelines of governance.” If that is nonsecular, than we are very happy to be considered nonsecular. And we don’t think that it runs counter to a healthy democracy; rather, it only strengthens it.

As both a religious and a political figure, do you view your roles as separate?

Although I am a fully ordained monk, I don’t consider myself a religious figure, at least not in my public capacity. Some of my friends suggested that I disrobe when I was elected Kalon Tripa [head of the Tibetan Cabinet-in-Exile]. I considered it quite seriously, but ultimately I see no conflict. I give greater priority to my position as Kalon Tripa, so my personal practice suffers, but that is my personal life. This causes me some suffering, but I have chosen to devote my time to my duties as a political leader.

Do you offer formal teachings?

No, I choose not to teach. Being a political leader, to act as a religious teacher is not very healthy.

Rinpoche, you say that your charter provides for limits on His Holiness’s powers. What is your relationship with His Holiness, and how does it inform your role as a political leader? For instance, what if the two of you disagree?

The word “relationship” is a very delicate word. I have a number of different relationships with His Holiness. And I do not mix them up. For instance, His Holiness is my teacher. And I am a disciple of His Holiness. And in all dharma matters, I obey him 100 percent. On the other hand, I have been active in the Tibetan Parliament-in-Exile for the last eleven years, so I’ve been involved with the government since long before I was elected to serve as its leader. When a political matter has been an issue, many times His Holiness and I have disagreed. His Holiness has one view, I another. But His Holiness is one of the most democratic persons I have ever known. He’s remarkably open-minded and highly rational; he respects reason and logic. Therefore, when we discuss matters at length, if I am able to convince him through reason and logic, His Holiness concedes. If I am convinced by his logic and reason, I take his view. So far, we have not failed to resolve an issue after thorough discussion. We have had no problems. I have never taken a position against His Holiness, and His Holiness has never imposed upon us anything we found unacceptable. Every decision is made through institutionalized democratic procedure and thorough discussion.

You’re said to be an adherent of the methods of Mahatma Gandhi’s satyagraha—nonviolent resistance—and more specifically, you apply it in response to the current situation in Tibet. Can you say something about that?

Yes, I’m a staunch follower of Gandhi. Although we have irreconcilable differences philosophically—Gandhi was a theist and I am a nontheist—Gandhi’s experiments with truth are a real inspiration to me. You see, Buddhists are considered to be nonviolent people. If I could condense the Buddha’s teaching into one word, I would say the word “nonviolence” best sums it up. But no Buddhist state has yet achieved a society totally free of violence. Tibet was a Buddhist country for more than 1,300 years, and yet the state remained at times violent. Even the Dalai Lamas were not able to abandon completely all use of military force. But Gandhi, for the first time, told us that the state can be nonviolent, and he elaborately explained how. So my understanding of Buddhist nonviolence owes a debt to Gandhi’s teachings.

I used to tell my friends that I always carry with me one Dhammapada and one Hind-Swaraj, meaning “Indian Home Rule,” which is an eye-opening and most inspiring booklet written by Gandhi. If I had to choose one or the other, I would choose Hind-Swaraj. Since my being is so influenced by Buddhism, I can manage without the Dhammapada. But I need Hind-Swaraj to understand day-to-day functioning in politics.

Is there any dissent with regard to your choice to rely solely on compassion-based nonviolence?

We are unanimous in this regard, but our choice in favor of nonviolence is not one made out of compassion only; it is a deliberate and deeply practical choice. Many people think that because Tibet is so small and powerless, nonviolence is the only option we have. But we often see less powerful or occupied peoples use whatever violent means they have at their disposal to achieve a desired end.

In the long run, and for generations to come, a nonviolent movement is much more skillful. For our government, it is a carefully considered choice, and one I think that will best characterize the legacy of the current Dalai Lama. Our choice will nourish and inspire future generations. It lays the groundwork for running a nonviolent state if Tibet regains its autonomy, something violent resistance would undermine. My dream of building a nonviolent society in an autonomous Tibet may materialize and it may not. But as a concept, as a vision, it is sustainable and very much realizable if we refrain from violence now.

War is always being waged somewhere. How do you convince a people that peace is a possibility and not a naive hope?

This is a difficult question, and I don’t think I will be able to answer it in a very organized way. As matter of fact, this very belief—that violence is unavoidable—is a root cause of violence; it is a self-fulfilling prophecy. The possibility of surviving through cooperation is extinguished from the human mind, and it is replaced with the notion of the necessity of competition, which seems to serve as the driving force of modern civilization. That is one thing. And there are others. For one, war is a very profitable business if you consider the arms industry.

Peace is possible, here and now. If peace were as much a priority as, say, economic expansion, there would be peace. There’s no lofty Buddhist philosophy that’s necessary to explain it. It’s very simple. Peace is absolutely possible if you stop listening to people who would have you believe otherwise, and if we truly wish it.

Tibetans face the challenge of change on the one hand and preserving their tradition on the other. How, for instance, will you build new institutions that are foreign to an earlier Tibet while preserving what’s uniquely powerful in your tradition?

Change is the law of nature. You have to go with it if you want to preserve the tradition. If you resist change, then the tradition will not survive. But there are different kinds of change: good, bad, and neutral. For example, we are changing our political system from an old, authoritarian system to a fully democratic one. This change is a huge one, and a good one. For many other nations, democratization has required hundreds of years and lots of bloodshed. But we have been able to go through it very smoothly, very nonviolently, and quickly. It is this kind of change that helps to preserve the Tibetan tradition, and reveals its strengths. But change due to external pressures on our culture, and particularly the process of so-called modernization, is negative. It poses a threat to our traditional way of life. It is this kind of change that we must resist, and we have: the so-called Cultural Revolution, for instance, which destroyed thousands of monasteries, libraries, educational institutions, and historical monuments, did not destroy us; our “Tibetan-ness” survived. But there are even bigger challenges. Consumerism has been quietly destroying the Tibetan tradition and has been the greater threat. It’s a big challenge, inside Tibet and outside. People are being affected by money and by affluence, and that is destroying our system in a way Chinese force never could.

Is there any way at all that those of you outside of Tibet can address the social problems that exist inside Tibet? Drugs, prostitution, the erosion of basic Tibetan values that “economic progress” brings?

It’s difficult, but I don’t think impossible. We are trying. The Tibetans inside Tibet very much look to the Tibetans in exile, and particularly to His Holiness, for guidance. So they are receptive to our attempts to reach inside Tibet.

Do you think that many people who were born in exile, who were born after 1959, will want to return to Tibet if return becomes possible?

There are many people who are willing to go back, and some already have.

Tibet has its critics. Some might say that if Tibet were to become autonomous, it would revert to the authoritarian system that predated the Chinese invasion. How do you view such criticism?

This criticism is totally baseless. If China had not occupied Tibet, Tibet would have been democratized fully and completely a long time back. Soon after assuming political leadership in 1950, His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama set up a reform committee to initiate the democratization process of the Tibetan Government. But due to Chinese interference, nothing could be achieved. After coming into exile in 1959, His Holiness’s first priority was to democratize the Tibetan Government-in-Exile. To this end, he announced the drafting of the future Tibet constitution. Tibetans in exile are now enjoying a quite matured democracy. His Holiness has declared that he will cease to hold any political position as soon as Tibetans in exile return to a genuine, autonomous Tibet.

Criticism, healthy criticism, is always welcome. A real friend is one who points out your shortcomings. So if your criticism is constructive, and you criticize Tibet in order to help the Tibetan people to improve, I am grateful. But I find there is a lot of criticism that is not very useful. Many people do not understand the very things they criticize about Tibetan culture, because they are looking through a Western lens. First, it’s always important to understand, in depth, what you are criticizing. And then the issue should be examined through both Western and Tibetan viewpoints. That way, when you offer criticism, it will be useful.

Rinpoche, obviously you have hope that one day you will return, or maybe people after you—

Not only do we hope, but we have faith, a strong belief, that we will return. And we think that we will return during the Fourteenth Dalai Lama’s lifetime. He must go back, and I think—no, I have faith—that he will go back, and all of us are working for that.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.