My father was in the army of occupation in Japan from 1946 to 1947. The only reason I knew this was because he kept his green fatigue jacket hanging in the closet with its 8th Cavalry insignia and private’s stripe. I’d take it down from time to time and put it on, but it was like trying to wear a tent (still would be; he was a half-foot taller than me). He never said anything about those years. It felt to me like a forbidden topic, as if something shameful had happened there, as it had for so many veterans. But he was not a combat soldier, and he spent most of his time in Japan on one base or another (first in Tokyo, then near Mount Fuji) lying in his “sack.” So it wasn’t silence due to PTSD.

Of course, it’s not as if my father was silent only about the army. He was generally silent. To me he was a strong and silent man just like John Wayne. Perhaps I was supposed to admire him for this quality, but my generation never understood the strong and silent routine. It was mostly irritating and disturbing. We were talkers, good talkers. That’s something that my dad didn’t get, all the talking.

In any event, the mystery of Japan had to take its place with the mystery of growing up in Kansas, the mystery of just what the heck he did at work, and the mystery of who the hell are you?

My only knowledge about his feelings for the Japanese came while driving in a car with him. He’d see an Asian driving slowly, or erratically, or just not as he thought a man should drive a car, and he’d say, “Damned Jap.” Or he’d say, “The only thing worse than a woman driver is a Chinaman.” Jap, Chinaman, they were all gooks to him. My childish but not illogical conclusion was that he hated “Japs,” and my not unreasonable assumption was that they must have done something bad to him when he was in Japan.

But they hadn’t.

I know this because after Mom died in 2009 my sisters and I got access to the forbidden boxes in the most obscure corner of the closet. In one of those boxes was an album of photos of my father and his friends taken when he was in the army in Japan, and there were a dozen letters to his mother written from basic training and from Japan. Reading these letters was like meeting him for the first time, in the malign innocence of his heart.

He was assigned to basic training at Fort Knox, outside Louisville, and then briefly, just before shipping out, at Fort Lawton in Seattle. He had the usual soldierly gripes about sergeants (though he would shortly be one himself, because the lieutenant had “taken a shine to me”) and boredom. The high point of these months was meeting a beautiful girl in Louisville.

I found a girl in Louisville & is she beautiful. I spent last weekend with her, we went to hear Stan Kenton at the Madrid Hotel so you can tell where my money goes.

In January 1947 he arrived in Japan. After months of worry about the hardships and uncertainties of duty in the army, this homegrown product of the fields of Kansas was astonished and pleased by the privileges afforded to conquerors.

Dear Mom: I’ll bet you can’t guess where I’m at. I’m in one of the biggest hotels in Tokyo. I’m pulling out post guard and it’s really the life of Riley. I’m on 2 hrs and off 12 which gives me a lot of time. We have a great big room to ourselves and Japs to clean it. There is a big bathtub sunk in the floor and I swear it’s big enough to swim a hundred yard dash in. I’ve never seen a bathtub so big before. It’s just like those ones you see in the movies.

In addition to callow wonder, there is also something deeper in this letter: a young man’s earnest self-reflection on where he is and what he’s doing.

Everything is really swell and the Japs are very polite to us. You can push these people all over & make them do anything, but I don’t consider that a way to preserve the peace & that’s what we are all over here for. As I’ve told you before, the Jap people are really depressed & will do anything for a cigarette & some food. I’ve always found out that the best way to get along with people is to be kind & nice to them & just because we live on one side of the pacific & they live on the other doesn’t make us superior.

“The best way to get along with people is to be kind”? Apparently buddhanature does sleep in every human being, but this is not wisdom he ever chose to share with me.

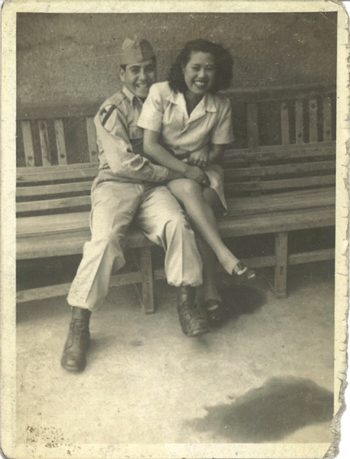

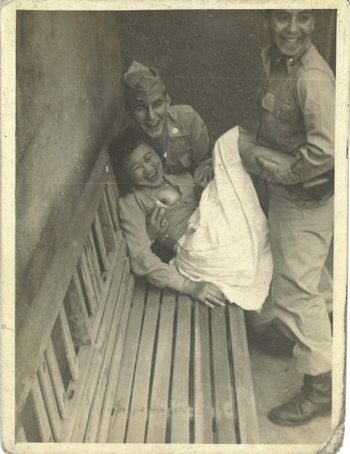

He was a sensitive, loyal, and very human soldier, but there was more to share that he didn’t tell his mother. Most important, he had a Japanese girlfriend. Her name was Yuki Muri, and it looks as if he met her at a Tokyo dance hall, the Kayo Palace (kayo means “song and dance”), where local girls offered themselves to GIs as dancing partners or for who knows what else. She was probably another impoverished young Japanese woman who found a source of income in being a taxi girl. Clearly, their relationship went some way beyond that, or how else to account for the formality, the intimacy, and the expense of this professional photo?

This picture is the very last in the album, his last and deepest thought. Beyond all the snapshots and then the pages left blank, this photo enjoys a dubious pride of place. It is buried and yet cherished, in an odd way.

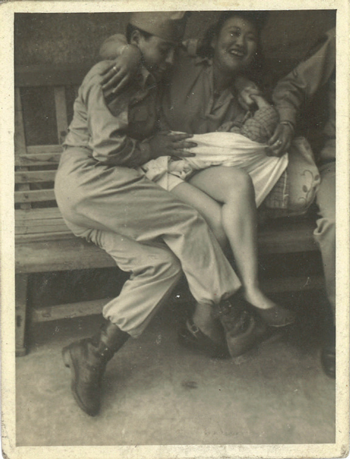

Now, truth be told, Yuki was not the only taxi girl that my dad and his pals knew. Also in the dusty black album there are two shots of Japanese girls dressed up for an outing:

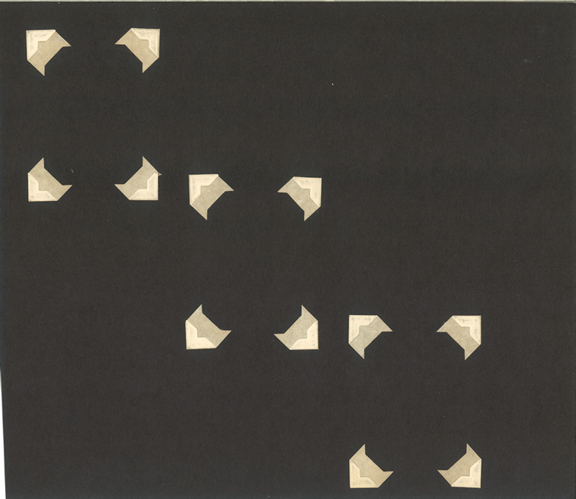

On the next page are three sets of empty brackets where photos once were.

This is what some enigmas look like.

I didn’t think anything of it at first; empty pages where photographs have been removed are typical of old family albums. But in a stack of unrelated pictures I found a clear plastic sleeve, the kind you’d have in a wallet, with three images, all of the girls who had posed so primly in the album.

|

|

|

This. |

Then this. |

And finally, in the malign innocence of their hearts, this.

As originally arranged in the album, the pictures would have created a sort of striptease moving from fully dressed, to a revealed thigh, and finally to the concluding satisfaction of a breast with a dark brown nipple. True, everybody appears to be having fun. It is also possibly true that they were already having abundant and, for the girls, prosperous sex. But it is also certainly true that this was not a way that the GI boys would ever have treated the girls back home. Kansas girls were nice girls. Sure, there was some sense in which the GIs liked the girls, and they gave them money, and cigarettes, and food, but in the end they could treat them to this sort of fun only because they were, for them, “Japs.”

But the big mystery to me is why my father would have gone to the trouble of carefully preserving memories of experiences that he didn’t want to talk about and probably didn’t want to remember. It’s as if there were degrees of repression. First, pretending to his children that he was never in Japan, not in any important sense, not in a sense worth talking about. Second, the deeper obscurity of the photograph album hidden from all prying eyes. Finally, and deepest, the removal of the three most incriminating photos of sexual mischief.

In the end, he did remember it all and he did tell us about it, because he never burned the album, he saved the letters to his mother, and he even saved, at their strange remove, the guilty photos. In this way, at last, he told us his story.

My conclusion is that he was ashamed of something, and not just the girls. They were a forgettable thing. Perhaps he was ashamed of Yuki, ashamed that he had been fond of someone Japanese, and ashamed that he had just left her behind, when he knew that for a while at least he had really cared for her. But then again, it’s not as if Japan was the only thing he didn’t tell us about; he was generally ashamed, ashamed of the whole thing, ashamed of his life. If he had looked at his shame and known it as shame, he would have been OK, he could have reclaimed his true self. Instead, he believed it, believed what his shame told him, without understanding the shame of his shame. It convinced him of his essential worthlessness, and he was never able to think of something to do with that beyond pouring Royal Gate vodka on it and perching on a barstool with fellow knuckleheads.

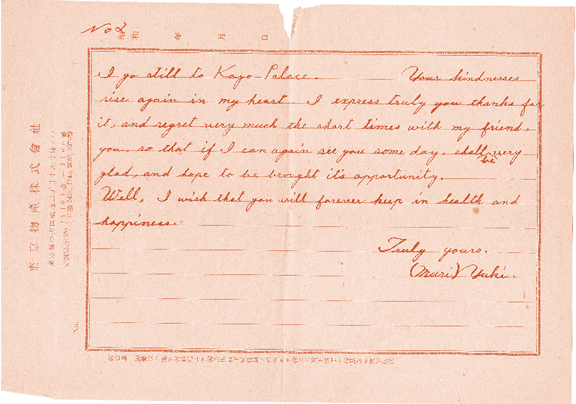

These images and letters are from such a critical point in his life. I can see here some of the material of his self-loathing, but I can also see his true nature, a nature that Yuki herself testifies to in a letter written a year after his last letter to his mother. This letter is absolutely the most remarkable thing in this little family archive of my father’s forgotten life. No one would have wanted to save it except him, so he was touched by it, and yet he surely never replied to it. Yuki was a detail from a life he was in the process of burying. (My father seemed to live his life with a shovel in hand.) But the fact that he kept it, the fact that he made no reply, and certainly made no effort to see her again (he started dating my mother just a few months hence) had to make him feel just a little like a cad, a sensitive cad capable of remorse, an understated echo of Puccini’s “bounder,” Pinkerton, in Madame Butterfly, but a cad nonetheless.

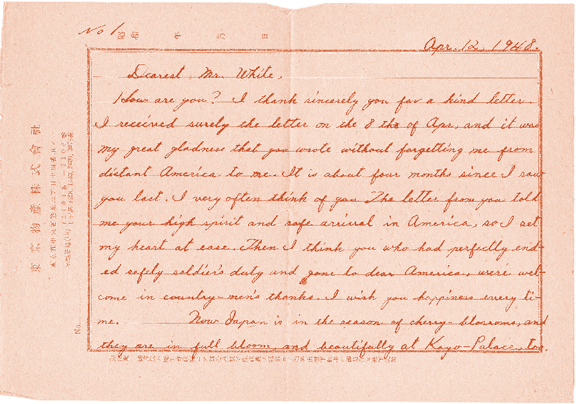

Still, there is Yuki’s touching letter and her generous account of my father’s true nature. However ambiguous everything about their situation must have been, she may very well have been among the last human beings allowed the privilege of knowing it; his was a badly damaged nature after that. This is her letter:

Dearest Mr. White,

How are you? I thank sincerely you for a kind letter. I received surely the letter on the 8th of Apr, and it was my great gladness that you wrote without forgetting me from distant America to me. It is about four months since I saw you last. I very often think of you. The letter from you told me your high spirit and safe arrival in America, so I set my heart at ease. Then I think you who had perfectly ended safely soldier’s duty and gone to dear America, were welcome in country-men’s thanks. I wish you happiness every time. Now Japan is in the season of cherry-blossoms, and they are in full bloom, and beautifully at Kayo-Palace too.

This is the part that I find most revealing, from the end of the letter:

Your kindnesses rise again in my heart. I express truly you thanks for it, and regret very much the short time with my friend, you, so that if I can again see you some day, shall be very glad, and hope to be brought its opportunity. Well, I wish that you will forever keep in health and happiness.

Truly yours,

(Muri) Yuki

I feel an odd sort of gratitude to this woman, this Yuki Muri, who knew my father’s true nature.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.