The gift of justice surpasses all gifts.

—Dhammapada 354

To pass judgment hurriedly

doesn’t mean you’re a judge.

The wise one who weighs

the right judgment and wrong,

the intelligent one who judges others impartially,

unhurriedly, in line with the Dhamma,

guarding the Dhamma,

guarded by the Dhamma,

he’s called a judge.

– Dhammapada 256-257

In the three decades that he has been an attorney and a Buddhist, Steven Schwartz has had many epiphanies in the meeting ground of justice and dharma, of law practice and Buddhist practice. One that sticks out in his mind is the case of Cathy Shine, a young woman who walked into the emergency room of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston following a midnight asthma attack. Cathy requested oxygen, but before she knew what was happening, the emergency room staff forcibly intubated and medicated her. When she tried to leave, ER personnel chased her and hauled her back. The horror of being tied and having a catheter shoved into her lungs so traumatized Cathy that she made her family swear never to admit her to a hospital, no matter what the consequences. Some months later, she suffered the severest attack of her life and, without hospitalization, died.

Schwartz argued the case of false imprisonment, forced treatment and wrongful death on behalf of Cathy Shine’s family in an atmosphere of what he calls “the worst vestiges of the legal system.” Harvard University, which owns the hospital, had rallied a phalanx of crack lawyers. As counsel for the plaintiff, Schwartz had to employ an arcane and elaborate form of questioning called the “expert hypothetical,” a method, used in a few states, for eliciting an opinion of an expert witness, whereby the attorney must include every single relevant fact that the expert must consider in forming the opinion. Moreover, each phrase of the question must be posed using hypothesis, such as, “Doctor, assume there is a woman who is twenty-nine years old and who has a long history of asthma . . .” If any one of the assumptions is not stated correctly, the entire question is ruled improper. Schwartz had never used this method before and at the trial, when he began to pose the “hypothetical” questions, he floundered. “I tried nine times, and each time I hadn’t constructed the question right, so it kept getting thrown out. But each time my mind state got deeper and deeper. First it got darker and darker—it was as if the world turned black—and I thought, ‘the problem is me.’ Then, I thought the problem was the entire system. And then there came a moment of perfect clarity when I realized: There is no problem. I saw that this is just how this woman felt when she was struggling to get free from the ER and, later, to make her case heard” (Cathy had been trying to publicize her ordeal at Mass General when she died). “I suddenly understood that this is what it means to be imprisoned. I was imprisoned by this ridiculous formula and process. I saw myself in the same space of suffering as Catherine had been, and I saw that the judges and the lawyers were there, too.”

Schwartz lost the trial. But the “dharma-understanding, the slap in the head,” that came to him, he says, brought a surge of “trust and faith” in the shared experience of suffering. A year later, at the Massachusetts State Supreme Court, he appealed the case and took it to victory for Shine’s family—and for anyone else who might fall into the same situation.

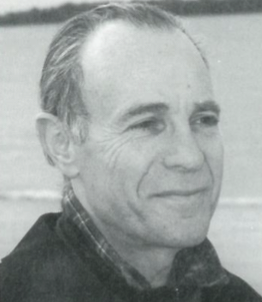

Tall and gracious, Schwartz has a head of silvery curls, a mustache like Butch Cassidy’s, and a calm, deliberate way of speaking that’s reminiscent of the meditation teachers he has spent so much time with. For twenty-seven years he has litigated on behalf of the disabled—largely, people with mental illness. In 1973, he opened the Center for Public Representation, a national public interest law firm, now located on a postcard-pretty street in downtown Northampton, where staff benefits include one week per year for a meditation retreat. For many years, Schwartz ran a legal office at the infamous Northampton State Hospital (like most mental institutions, Northampton State did not allow most patients to leave the grounds—or even the ward—to meet with their attorneys, so a legal office existed within the hospital) and during his tenure there the dozens of criminal and civil suits that he and his staff brought against the state were instrumental in closing down the institution in 1993. There were suits to stop the hospital from putting people in cages, suits against sadistic guards (one who threw paint thinner on a patient), suits to get the hospital to provide the treatment it was supposedly there to offer and, mostly, suits against involuntary commitment. To this day, Schwartz’s center runs legal offices in most of the mental hospitals still open in the state. Since 1971, after graduating from Harvard Law School and lighting out for India (“because I wasn’t ready to practice law”), he has been a meditator, studying first with S. N. Goenka and then with Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield, co-founders of the Insight Meditation Society.

Certainly there are other lawyers who could and would have taken on the Shine case, and others who migh t have experienced a similar set of frustrations—even the same outcome. But Schwartz’s dance with emptiness on a courtroom floor, which he likens partly to “the sort of awakening experience that usually occurs on a meditation cushion,” was the culmination of years of Buddhist practice, braided with his legal work. For almost three decades, during the first m

t have experienced a similar set of frustrations—even the same outcome. But Schwartz’s dance with emptiness on a courtroom floor, which he likens partly to “the sort of awakening experience that usually occurs on a meditation cushion,” was the culmination of years of Buddhist practice, braided with his legal work. For almost three decades, during the first m inutes of his daily morning meditation, Schwartz has made a mental draft of every single legal argument of his career. In these meditation sessions, as on that courtroom floor, Schwartz plumbs the nature of his relationship to the person he’s representing. “It’s a fundamental koan for me,” says Schwartz. “I call it the ‘same or different’ koan. Seeing the sameness between me and the client inspires me to use the difference impeccably. It ceases to be work, and becomes an opportunity.”

inutes of his daily morning meditation, Schwartz has made a mental draft of every single legal argument of his career. In these meditation sessions, as on that courtroom floor, Schwartz plumbs the nature of his relationship to the person he’s representing. “It’s a fundamental koan for me,” says Schwartz. “I call it the ‘same or different’ koan. Seeing the sameness between me and the client inspires me to use the difference impeccably. It ceases to be work, and becomes an opportunity.”

In the simplest—and probably the most common—terms, the present state of the American judicial process runs counter to the tenets of Buddhism. It is predicated on an adversarial system that places people in mutually exclusive positions: victim and perpetrator, prosecution and defense, forces of good and forces of evil. It seeks to assign blame to perceived offenders and mete out punishments that, in theory, match the crime. A staggering number of those punishments, for nonviolent as well as violent crimes, are prison terms: In 1999 there were nearly 1.5 million prisoners under federal or state jurisdiction—that’s 468 inmates for every 100,000 Americans, up from 220 per 100,000 in 1990. It is a system that reifies the worst racist tendencies of our society, too: Black male inmates outnumber white male inmates by almost ten to one. Hispanics outnumber whites by three to one. And to top it all off, some 4,000 inmates, in the 38 states that approve capital punishment, are slated for execution. Last year, 98 death row inmates were executed—which, from a Buddhist view, is a profound perversion of justice. For 2000, the number is already approaching 50. “The ineluctable foundation of the legal system is dualism,” says Albert Kutchins, a criminal appeals attorney who lives in Berkeley, California, and has studied Zen for 15 years. “It’s about who’s right and who’s wrong. It’s about a closed system of thought based on binary Western thinking.” Force, violence, and the stripping away of freedom are the law’s modus operandi for suspected and convicted criminals.

If the judicial system aggravates suffering in its convicts, it is also rough on its servants. The culture of law can be a cold, antagonizing, and unforgiving place. Most lawyers live in a world of words, confrontation, and action—all focused on achieving results and, above all, on winning. At best, it is a world where only the cognitive and analytical mind counts. At worst, what has arisen as legal culture in the United States is a crucible of intense competition, aggression, cynicism, overwork, alienation, judgmentalism, and deceit. Those qualities of behavior are widely promoted—even mandated—and directly or indirectly rewarded in law school and legal practice. It is greed, anger, and delusion, writ large. As Schwartz puts it, “Law is mostly a tool of powerful people to make money and oppress other people.”

The strain on relationships among judges, lawyers, and clients is intense. Steven Keeva, a meditator and editor of theAmerican Bar Association Journal in Chicago is also the author of Transforming Practices: Finding Joy and Satisfaction in the Legal Life, a book about integrating a spiritual or contemplative practice into legal work. Keeva has talked to a lot of lawyers and paints a bleak and anxious professional, emotional, and spiritual landscape. “In the law today, you run the risk—first in law school, then in practice—of overlooking the central fact of human life that makes laws necessary in the first place—that we are formed by a web of relationships,” he writes. As a result, reports Keeva, the sense of isolation and discouragement in the profession is reaching a critical mass.

But law as it mostly is and law as it can be are two different things. “In its most formal and best sense, law is a vehicle for alleviating suffering,” says Schwartz. As he and many other Buddhist legal professionals like to point out, one definition of dharma is “law”: In the Buddha’s teachings, that “law” refers to the natural law of karma. In a broader sense, the dharma underlies the whole of the universe, but as it’s expressed in society, it gives rise to systems that people must observe if they want to get along, namely the Buddhist teachings. As Schwartz sees it, the truth of dharmic law and the “truth” of legal law can reinforce one another. For contemporary practitioners, working in the law is bodhisattva work, an opportunity to deliver compassion where it usually never goes; a place, like any other, to watch the law of karma at work, to cultivate wisdom and the realization of emptiness. And for a growing number of lawyers and judges, Buddhist meditation offers a technique for recharging and looking inward and working through the afflictive emotions that populate the legal universe.

Laurel Greene*, a criminal defense attorney in Los Angeles, says practice gives her “that extra beat—to observe without reacting—which most people don’t have. With a huge caseload in a setting akin to an ER, it’s too easy to burn out, to lose your sense of compassion, and to lose your cool, without a set of tools for managing your mind.” Dharma study—and meditation practice in general—is wielding more and more influence on the legal professions. For the past three years Mirabai Bush, a Buddhist who runs the Center for Contemplative Mind in Society in Williamstown, Massachusetts, has been organizing retreats to introduce meditation to Yale law students and professors, and the program is expanding to other law schools. In researching his book, Keeva discovered dozens of attorneys who were integrating a contemplative dimension into their law practice as an antidote to its inherent stresses and contradictions. And at the law schools of Suffolk University in Boston, Denver University, and Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Buddhist law professors offer courses on integrating mindfulness and contemplation into legal practice and criminology. Whether Buddhists, and meditators in general, will bring about substantive change in the judicial system remains to be seen, and this may not be the point. But as Joseph Goldstein, who has taught at each of the three Yale Law School retreats, sees it, the groundswell of interest in meditation parallels what has happened in the world of medicine. “In the health community, meditation has become acceptable, even mainstream, especially in the area of stress-reduction work. We’re at the very beginning of seeing that happen in the legal profession.”

Once upon a time a Buddhist legal system did exist, and dozens of passages in the Pali canon point to its origins. In the Vinaya, the monastic code, the Buddha fine-tuned a disciplinary system for his sangha that dealt with misbehaving monks. And throughout the code there are scores of examples of case law wherein a monk who committed an offense would be deemed “defeated”—that is, “he loses all power to meditate, and thus all the powers that he had acquired by meditating,” writes Andrew Huxley, a British professor of law and Oriental studies at the University of London, in an article on “Buddhist Case Law on Theft” that appeared in the online Journal for Buddhist Ethics. “A monk who steals [for example] has ‘ipso facto excluded himself from monkhood.’”

“If a monk were committing an offense, making amends, and then doing it over and over, a sort of council would convene,” explains Thanissaro Bhikkhu, a monk in the Thai forest tradition who is the abbot of Metta Forest Monastery and a prolific translator of the Pali canon. Within the kind of tribal setting that characterized the Buddha’s sangha, punishments for the monks ranged in severity from stripping a monk temporarily of rights, prohibiting him from being attended by junior monks or making him stand at the back of the alms round, to outright banishment from the community. Ostracism was one of the worst punishments. According to Thanissarro Bhikkhu, “What’s interesting is that in all cases, the punishment was described as rehabilitation—not punishment for punishment’s sake, or making the guy pay his dues but rather, if he goes through this, he will change his ways.” Punishments, too, were tailor-made for the offender as, from the Buddha’s view, a monk’s nature dictated what sort of reprimand would be effective.

In the centuries following the Buddha’s death, Buddhist kingdoms (and later, nation-states) tried to institute social and legal justice systems in line with the dharma. In India, kings, who also served as judges, were known as dhammatha—literally, conveyors of the dharma. The political model for a good leader was the canon’s “wheel-turning monarch” or “righteous king” (described in the Long Discourses of the Buddha) who lived according to the Five Precepts (no killing, stealing, lying, sexual immorality, or use of intoxicants), and tried to get his subjects to do the same. And the laws he prop-agated were supposed to reflect the natural laws of karma. The first historical example of such a king was Ashoka, the third-century Indian king, who had a three-pronged Buddhist government: He taught the dharma to his subjects, practiced the dharma, and tried to create laws and administrative channels that would address people’s grievances easily. In other words, writes Winston King, a professor emeritus of religion at Vanderbilt University, Ashoka dealt “with such problems as theft, violence, and aggression by benevolent social welfare measures that removed their social and economic causes. ‘Justice’ here—though the term is never used—might be termed the justice of preventive benevolence, a motif that appears in most later Buddhist formulations of a code of conduct for a Buddhist ruler.”

Today, Buddhist lawyers and judges are not so much looking to create a dharmic legal system as to function skillfully in their jobs, and in the rest of their lives. The potential for broader change is viewed as a positive by-product of personal transformation. For seven years Laurel Greene has studied with Thanissaro Bhikkhu, whose monastery near Escondido, California, is about two hours from Greene’s home. Greene likens the forests and cemeteries where her teacher and his dharma ancestors meditated and practiced with their fear of snakes and tigers and ghosts, to her very own forest—“the judges and the D.A.’s and the clients and the crime victims. I’ve seen more burned and dead babies, more severed heads than you’ll ever get in any charnel ground.” On one visit to the monastery, Greene’s teacher told her to try practicing breath awareness all day long. “I thought he was out of his mind,” she says. “His forest is very different from my forest. I couldn’t believe that paying attention to my breath could in any way be a protection. I thought, “You have no idea how often I have to think.’” But after a while, it worked. “It took me a long time before I could do hearings where I was conscious of the breath the whole time, even when I cross-examined a witness. It was amazing to find that I could listen, really listen, to everything that was being said, on every level.” Her process of transforming work—life through dharma also included the Five Precepts. “If you follow the precepts, your life simplifies enormously. You give things up, and that sort of renunciation removes a ton of clutter from your mind. When you work long hours and have a very programmed life, as most lawyers do, this allows you to be present in a place that’s not complicated. You never have to think about what’s going to happen next, because you can relax in the knowledge that you’re going to do what’s appropriate.” Realizing the law of karma at work, Greene says, “I can see causation coming from so many different places, and I’m only one of the factors spinning around. But I can step back and watch it happening.”

It was that same recognition, in part, that convinced Cheryl Connor, a former prosecutor with the Massachusetts Attorney General’s office, to quit practicing law. “I spent all my time going through documents trying to figure out how people had defrauded companies of money. But after you’ve studied the nature of mind, it’s impossible to think that anyone is simple-minded enough to do that just because they’re a criminal. There’s an extraordinary amount of karma that leads someone to commit those kinds of acts.” Today Connor is a professor at Suffolk University Law School in downtown Boston, and helps run the clinical internship program there. She also teaches a course called “The Reflective Lawyer: Peace Training for Lawyers,” which incorporates dharma and meditation instruction. And at the suggestion of her teacher, Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche, she is writing a book on dharma for legal professionals for use in classes like hers.

Listening—and its corollary, silence—are two of the most basic ways Buddhists say practice helps them. Robert Burt, who teaches at Yale Law School and co-led the first meditation retreat there, says lawyers have trouble listening because they’re busy ticking off mental checklists that get in the way of their clients’ stories and because they cannot tolerate silence even for the short space it takes clients to gather their thoughts. Joseph Goldstein noticed the same thing among the law students he taught: For most of them, it was the first time they’d ever experienced sustained silence. “By the end of the retreat,” he says, “they had come to appreciate silence, both for its rejuvenating quality and for its clarity.”

Ron Greenberg, a retired judge, says he’s learned to embrace silence and “not-knowing” in a job that demands fast answers and snap judgments. “Over and over I’ve heard prosecutors and judges say, ‘I’ve heard that story before.’ But if you’ve heard it before, you weren’t listening.” Greenberg, who has practiced law for thirty-two years, eighteen of them on the bench, and whose meditation practice has been informed by vipassana training and the teachings of Thich Nhat Hanh, ran an innovative court in Berkeley, California, dedicated to hearing drug cases involving defendants who are addicts. He would begin each session by dimming the courtroom lights and sitting in meditation for five minutes. The effect of this technique, he explains, helped defuse the tension that lawyers, defendants, and their families bring to the session.

Of course, tension, and even anger, are staples of the legal process. Many young law students view moral outrage as a wellspring for fighting injustice. At the Yale Law School retreats, says Goldstein, the roles of tension and anger were the most controversial. “I was trying to put forth the possibility that compassion for suffering might be a more productive and sustainable energy than anger at the injustice,” says Goldstein. “But there were many people who felt they needed righteous anger in order to be effective. One student said he was really cultivating anger, that he needed that energy as an antidote to his fear [of failing as a lawyer]. So we talked about accepting that fear, of getting okay with it as a way of freeing oneself from it, rather than using anger as a way to suppress it. This was the hardest notion to swallow.”

For most people, the notions of judgment and blame are inseparable from anger. And that paradigm lies at the heart of the gap between a Buddhist view and the creed of a Judeo-Christian judicial system. Connor, at Suffolk Law School, has a bird’s-eye view of the contemplative legal movement in this country and runs a group called Lawyers with a Holistic Perspective. About 180 attorneys with a contemplative practice—Buddhist, Jewish, Hindu, Mennonite, and other strains of Christianity—take part in monthly meetings, and this is where Connor sees the most pointed difference between her Tibetan training and the vantage point of some of the Christian contemplative attorneys she knows. “From a Christian perspective, ours is a just God and a wrathful God. Buddhism has wrathful deities, but it doesn’t talk about wrath being meted out by a god. I think that notion is leaned on to justify a lot of punishment. There’s an awareness in our tradition that if a punishment carries anger, it loses its benefit.”

Many Western Buddhists believe that judging runs counter to insight and unconditional compassion, that passing judgment automatically implies a troubling duality, a delusional moral hierarchy. The Buddha, however, warned not against judging, but against being judgmental. The former implies clear comprehension of appropriate action and the latter implies bias and misconception. Before becoming director of clinical programs for the University of Denver College of Law, Jacqueline St. Joan practiced law in Denver for ten years as an assistant attorney general, a deputy district attorney, and as a private practitioner. She was a judge in Denver for seven years, where she was instrumental in establishing the first protective orders court for cases involving domestic violence. During her time on the Denver bench, St. Joan delved deep into Buddhist practice, under the aegis of the Tibetan lama Thrangu Rinpoche and one of his students, Debra Ann Robinson. “Debra, my meditation teacher, helped me to understand the difference between judgment and the need to judge, that an application of intelligence with clarity is what we call judging,” says St. Joan. “Intelligence includes compassion. It’s okay to judge. I began to see what my role was and what it wasn’t, and that it wasn’t unimportant. People’s lives occurred before I met them and went on afterwards. But if you’re sentencing them, you’re part of something much bigger. If somebody had spent years developing habits that led them to driving drunk or abusing their children, it wasn’t for me to overlook that but for me to observe it and respond appropriately. To the extent that delivering consequences affects behavior, I can sometimes see the need for probation or jail time.”

While Buddhism looks at the absolute dimension of freedom—it doesn’t matter where you are or what’s happening, as long as your mind is free—few Buddhist lawyers and judges find anything philosophically intriguing about jail time. The first time Greenberg sent someone to prison was eighteen years ago, and he still reflects on it all the time. In fact, the experience affected him so deeply that he became known as a lenient sentencer and in 1994, a D.A. ran a law-and-order campaign against him. The dharma, Greenberg says, gave him “permission” to refrain from making a decision before he’s ready. “This practice has taught me to take a step back, to say, ‘I don’t know,’ if I don’t. How can you make a decision in a few hours when you’ve heard weeks of testimony?”

The judgment that concerns Laurel Greene is not with the clients but with the system as a whole. “People ask me how I can do this. How can I defend someone who has attempted kidnapping, or raped, or shot someone? I go into a different gear. I don’t think for these clients there’s anything remotely resembling justice. I believe in the jury system, but I don’t believe D.A.’s file cases properly, and I can’t believe witnesses testify honestly. It’s my job to be there, focused, vigorously defending the few rights this person has. Ultimately, the question for me is not whether they’re guilty or innocent. What I’m after is the best outcome this client can get with my involvement. How can I make sure the system does its job and causes the least amount of suffering?”

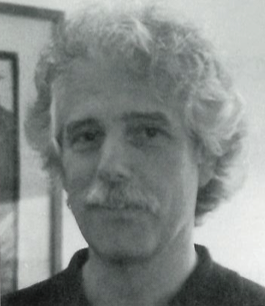

Albert Kutchins, who has been practicing law for nineteen years and specializes in criminal appeals, sees his job in much the same way: “The luxury of doing appeals is not talking about getting anybody off, or about guilty or not guilty. You’re saying somebody is due a fair trial.” Most of Kutchins’s clients, like Greene’s, are convicted of murder, rape, and other serious felonies. But unlike some of his colleagues in the dharma, Kutchins doesn’t see a seamless overlap between being a Buddhist and being a lawyer. “In terms of doing the work itself,” he explains, “it’s pretty hard to bring practice to my work except in certain situations. It helps when arguing a case in court. I have the training in just showing up and being available for whatever happens. But as far as perfect integration goes, I have no doubt that a great adept could do it, but I see conflicts all the time.” Sometimes those conflicts are resolved through accommodation—and staying away from work that violates the precepts. For Buddhist judges like Greenberg and St. Joan, that means sending people to jail only after all other options have been exhausted. For St. Joan, it meant drawing the line at death penalty cases, which she wouldn’t rule on. “I came to realize that I was operating within a system that relies on force,” she says of her time on the bench. “If someone violates a court order, it’s off to jail. If someone misbehaved in court, I could push a buzzer and they’d be hauled off to jail. It’s all coercive, aggressive, and violent. At a certain point, I decided I could reconcile myself with that, but on the death penalty I was not willing to compromise.”

Gestures of enlightened behavior often start out small—and make ever-widening ripples. Such is the story for Margaret Zaleski, a judge who lives near Boston. Zaleski describes herself as having “a calling” to be where people are suffering. She practiced Zen for a few years, and for the past five has been studying vipassana, “trying to settle my mind.” Last year she went on her first metta (lovingkindness) retreat with Sharon Salzberg. “It was so luscious,” says Zaleski, sitting in an office in the judges’ lobby at the Dorchester District Court in Massachusetts. “When I left, I vowed to take that into the courtroom with me.” Every day, Zaleski is assigned to a different court, and often as not she lands in Dorchester, a racially segregated, working-class satellite south of Boston. A few paces from the bland modern block of a courthouse on Main Street, street life resembles that of a lot of inner-city neighborhoods—decrepit buildings, people milling around drinking malt liquor, abandoned cars. Inside, the building has the atmosphere of a newly built hospital: a clean and highly functional place where most of the people waiting are tense and anxious.

On a recent afternoon, Zaleski ruled on case after case, nearly all involving drug arrests and nearly all with African American defendants. As each approached the bench, Zaleski said hello, and her smile seemed motherly and bashful at the same time. One middle-aged woman in an orange prison jumpsuit and handcuffs was led in. A young woman, the D.A., delivered a description of the crime in a monotone: “A common and known criminal” had robbed a store with three accomplices and ended up dragging the shop owner down the street behind the getaway car. The woman had needed money for a fix. “How’s the treatment going?” Zaleski asked her, about a prison drug rehabilitation program. “Very well,” answered the woman, whose face was lined with scars. “Do you think it’s working?” “Yes, definitely,” the inmate replied. Zaleski asked a few more questions about the defendant’s life, then set a date for her trial. “A court like this is a human treadmill,” Zaleski says. “I try to do what’s required for the job from a base of love and compassion. I’m not doing anything different or extraordinary. But I recognize that the person in front of me is me.”

Without a key to Zaleski’s motivation, her behavior on the bench seems like common decency—skillful means of the sort anyone, particularly someone engaged with a spiritual tradition, would employ. But in contrast to what most Dorchester defendants are used to hearing, in a system where phrases like “common and known criminal” have become banal, a judge’s interest in a perpetrator’s well-being is radical. In many fundamental ways, what is extraordinary about the application of Buddhist practice in justice work lies in the ordinary details: of being better and more patient listeners, more compassionate judges; of being noncombative courtroom advocates and creative litigators. As Steven Schwartz puts it, “If you can navigate someone through the greed and violence and rudeness of the system, then you are working in the dharma.”

*Laurel Greene is not her real name. She did not want to be identified for purposes of professional anonymity.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.