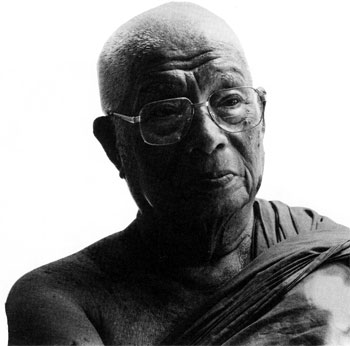

THE VENERABLE Buddhadasa Bhikkhu, who passed away at the age of eighty-seven on July 8, 1993, was perhaps the best-known and most controversial Thai monk in the contemporary Theravada tradition.

Although adhering strictly to the conservative Vinaya rules established by the historical Buddha, he claimed that to practice religion seriously one must be both conservative and radical. Hence on his eighty-fourth birthday a volume was published to honor him, with the title ofRadical Conservatism: Buddhism in the Contemporary World. Contributors included His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Thich Nhat Hanh, Bhikku Sumedho, David W Chappell, Lewis R. Lancaster, Donald K. Swearer, and others.

Traditionalists attacked Buddhadhasa because he regarded Mahayana as being as important as Theravada. He even questioned some remarks made by the most famous Theravada commentator, Buddhagosa. Besides, he praised authentic teaching in the Bible and the Quran.

He said his aims in life were three:

1. Those who claim to follow any religious tradition should understand and practice according to the essential teaching.

2. Those who belong to one religion should respect other religions.

3. We should all unite against materialism, which is connected directly or indirectly with greed, hatred, delusion.

His teaching was not only for personal happiness but for social justice and ecological balance. He proposed dhammic Socialism as a Buddhist alternative to capitalism and communism.

It was as a result of Buddhadasa’s writing and teaching for the past fifty years that young Thai have come to realize the importance of Buddha dhamma once more. Previously they associated Buddhism with superstition and a nation-state. With his help, they now understand the essential teachings of the Buddha on selflessness, mindfulness, understanding, and compassion.

Buddhadasa taught that since Buddha was born in the forest, was enlightened in the forest, and passed away in the forest, we should really respect and preserve the forest. And since the word for a temple or monastery in Pali also means “forest” or “park,” we should really live openly in natural surroundings.

In 1932, he established Suan Mokh, the Garden for Liberation. Here he sat all day beneath the trees, surrounded by dogs and chickens, birds and bees, contemplating deeply. Donald K. Swearer has called him the Nagarjuna of Theravada.

Some of his works have been translated into several languages. Those in English are Handbookfor Mankind, Mindfulness with Breathing: Unveiling the Secrets of Life, Buddha-Dhamma for Students, Keys to Natural Truth, Heartwood of the Bodhi Tree: the Buddha’s Teaching of Voidness, and The Buddha’s Doctrine of Not-Self.

After his eightieth birthday, Buddhadasa often said that his mother was the most important person in his life. Yet he felt that he had not done enough for her. So he wished to form a new religious order for women called Dhamma Mata, one that would avoid the existing controversy in Thailand over the formal ordination of Bhikkhuni (nuns). His thinking was that if members of this new order are well trained spiritually and educationally, their positive contribution to humankind would overcome prejudice against their gender.

Seriously ill for the past ten years, Buddhadasa refused Western medical treatment, with its advanced technology. He wanted to die a natural death and to face death meaningfully, as a Buddhist monk should. In his final days, before he lost consciousness, he asked his monk attendant to read to him the Thai edition of Thich Nhat Hanh’s Present Moment Wonderful Moment. He told the monk to practice according to the teaching contained in the book. He said he too would practice accordingly—to be mindful all the time. Those were his last words.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.