In 1976, Venerable Karuna Dharma was the first woman to become a fully ordained member of the Buddhist monastic community in the U.S. She has continued to break new Buddhist ground by orchestrating three Grand Ordination ceremonies since 1994 for women of all Buddhist traditions. Close to fifty women have become fully ordained nuns, or bhikkhunis, in these ceremonies.

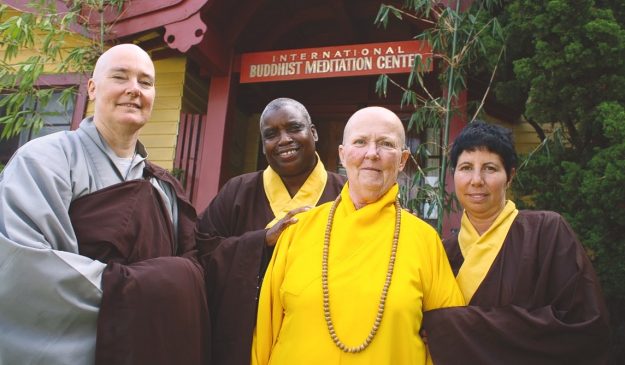

Ven. Karuna was born Joyce Adele Pettingill in 1940 to active Baptist parents in Beloit, Wisconsin. In 1969 she signed up for a class in Buddhism, where she met her Vietnamese Zen master, Venerable Dr. Thich Thien-An. She helped him found the International Buddhist Meditation Center (IBMC) in Los Angeles in 1970 and became the abbess there after his death in 1980. A recognized Buddhist scholar, Ven. Karuna is a past president of the American Buddhist Congress and current vice president of the Buddhist Sangha Council of Southern California and the College of Buddhist Studies.

In 1994 she suffered a serious stroke, but she regained speech and mobility that same year and managed to organize the first of three Grand Ordinations that included three major Buddhist schools: Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. For each ordination she reached out to sramanerikas (novice nuns) who wanted to become bhikkhunis. Women came from all over the world to be ordained by her. This was a giant step on behalf of women in Buddhism, especially considering that in some Theravada countries, like Thailand, a nun can be arrested for wearing the robes of a bhikkhuni.

Ven. Karuna’s ordination work has been most significant for women in the Tibetan tradition who are denied full ordination in their own temples. While the Buddha ordained both men and women and the bhikkhuni lineage continued after him in Mahayana countries like Vietnam, China, and Korea, it died out in Theravada countries like Thailand and Sri Lanka, and never entered Tibet. Traditionally, ten bhikkhunis are required to ordain novice nuns. As of now—without ten bhikkhunis in any Tibetan temple—their teachers can bestow only the purple robes of a novice nun, and the students remain novices for the rest of their lives.

Related: Bhikkhuni Ordination: Buddhism’s Glass Ceiling

The First International Congress on Buddhist Women’s Role in the Sangha will be held in Germany, at the University of Hamburg, in July 2007, and will feature Ven. Karuna as a speaker. The symposium hopes to conclude the long ongoing debate about reestablishing the bhikkhuni order around the world. His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama will be participating in the conference and has publicly stated his support of the recognition of Buddhist nuns.

Ven. Karuna has been my teacher since 1991, and I took the vows of a Dharma Teacher in her order in 2004. This summer—after lunch at my apartment in Playa del Rey, California—we spoke about the legacy of the bhikkhuni order, the changing role of women in Buddhism, and the effects of those changes on the longstanding Buddhist patriarchy. Ven. Karuna has always had a very no-nonsense approach. In true Zen style she always says what she thinks, and this day was no exception.

—Mira Tweti

You were the first woman to be ordained in the U.S., but weren’t there other bhikkhunis here at the time? There were very few bhikkhunis at that time. In fact, there were no other bhikkhunis at my ordination. I was not only the very first American woman to be fully ordained in the States, but also the very first woman to become a bhikkhuni here. Before that time you had to go off to Taiwan or Hong Kong or some place like that to get ordination.

Did you see it as a momentous event for women in Buddhism? It didn’t seem particularly important to me at that time. I didn’t think of it as a big groundbreaking thing. I just knew that somehow I had to become a bhikkhuni. I can’t explain it. Just something inside me said I had to become ordained.

You have been very involved since then with organizing grand ordination ceremonies that include women. How did these events come to be? In 1994 I had some male students who were ready to become bhikkhus. Venerable Dr. Havanpola Ratanasara was in the college [of Buddhist Studies] office. I went down to see him and I said, “Bhante, I have some students and it’s time for them to become bhikkhus. Would you be willing to be our Upajjhaya?” Upajjhaya means the main ordaining master. And he said, “Karuna, I would be honored to be the Upajjhaya!”

With some trepidation I said to him, “Bhante, there’s one little problem. My students think that since I’m their teacher, I should ordain them, but I know that I cannot ordain men.” He said, “Let me think about this.” After a few minutes he said, “My job as the Upajjhaya is to make sure that whoever leads the ordination is qualified to do it. And I want you to lead it.” I thought about it that night, and when I came down the next morning I said, “Suto, I’m very honored that you appointed me to be the ordaining master, but I don’t think I should do it alone. Let us share the job.” And he said, “That’s a wonderful idea.”

So we sat down to do the program for the ordination and we broke it in half. Instead of having three main ordaining masters, we had six: three men and three women. We had twenty more masters sitting up on the dais—ten men and ten women—and we also had another twenty or so who came along as witness masters.

You told me that Dr. Thien-An started the tradition of inviting all the different traditions to ordinations, and that mindset is why he named the center he founded the International Buddhist Meditation Center. Dr. Thien-An said, “You are an American, and this is going to be Buddhism in America. We should not limit the ordination to our particular school.” In fact, there weren’t very many Vietnamese around at that time anyway. He said, “I’m going to invite masters from all the different Buddhist traditions.” So he did, and they all came to the ordination ceremony. And I’ve carried on that same tradition because I think it is a very excellent way to do it. As Suto said, “We are not ordaining people into a particular Vinaya [set of rules and regulations for the communal life of monks and nuns]. We are not ordaining them into a particular school of Buddhism. We are ordaining them as monks and nuns, period.”

Is that because it was Buddhism in America, where all traditions are represented, unlike Asian countries that each have a specific tradition? Not only that, but also because that is the way it was in the beginning with Shakyamuni Buddha. There was no such thing as denominations in Shakyamuni’s time.

How does it work exactly? Because even though there were many traditions represented on the dais, you’re my teacher and you come out of the Vietnamese lineage, and when people ask me, I say that is my lineage. When I ordain people they put on the robe of their own school. So if you are a Tibetan you put on the Tibetan robes, if you are Vietnamese you put on those robes, if you are Theravada you put on the Theravada robes. That is why our ordination ceremony looks very different from others’.

Before the ceremony in 2004, I sent out a package to each candidate with information and an agreement. In order for her to come to the ceremony she had to write to her teacher and have her teacher sign the agreement that she was ready to be ordained and also that he would look out for her for at least five years afterward. Because for the first five years you are not free to just go and do whatever you want. According to the Vinaya, you have to be under the tutelage of your master. The masters all signed that agreement. We kept it fairly straightforward and strict that way.

After getting their agreement signed and traveling to L.A., all of the women had to stay at IBMC for at least two weeks ahead of time for the traditional ordination training. We had women who came in from Germany, Switzerland, France, Spain, Australia, and both coasts of Canada. A lot of women came and most, but not all, were Tibetans. There were a few Theravada women who became ordained. We ordained twenty women in all.

Why is it important to have bhikkhunis? The same reason it is important to have bhikkhus [male monastics]. The sangha [community of monks and nuns] protects the dharma, they carry on the traditions. If no one would fully ordain, who would do the teaching or carry on the traditions? You never ordain to get more enlightenment—you have to do the practice to become enlightened. A layperson can become enlightened as well as a monk.

In addition to the traditional bhikkhuni ordination, which requires 348 vows to be taken, you gave out Dharma Teacher ordination, requiring just 25 vows, to both male and female students. I know Dr. Thien-An started this revolutionary practice. Would you talk a little about it? It is revolutionary. Dr. Thien-An had lived in Japan for seven years, and he fell in love with Japanese culture. Almost all monks in Japan are married. They do not take the traditional vows of a bhikkhu. They take 25 special vows of Zen priests. That’s what you and your dharma brothers took in 2004 instead of the 250 for the bhikkhus and the 348 for the bhikkhunis. “Dharma Teacher” to me is equivalent to “bhikkhu” or “bhikkhuni.” They’re not laypeople, because they received the same training as the bhikkhus did.

Does it matter? Is there a loss to us in not taking 348 vows? It depends on what your goal is in being a monastic. If you want to be a true monastic, you should probably take the full 348. But if you want to be more like a missionary type, out there with the people, not living in a temple, it’s best that you take the 25.

Are the Dharma Teachers recognized in Buddhist circles worldwide? I have no idea if they are accepted worldwide. Some of my Sri Lankan friends say that we’ve added another level of ordination. But they accept when I tell them that I see Dharma Teachers as being on the same level as bhikkhus and bhikkhunis. That’s the way I look at it, and that’s the way Dr. Thien-An looked at it. I have no idea how everybody else looks at it.

Do you think Buddhist clergy in traditional Buddhist countries take American Buddhism seriously overall? I think they do. Many Asians when they first meet Americans have no idea of the Buddhism in America. They have no idea of the wonderful dharma work that’s being written in English. In some ways they think we don’t know Buddhism the way they know it, but when they begin to understand that we do know it the way they do, their attitudes change.

Tell me about the Buddhist conference you just attended. What’s the purpose of it? I went to the Sakyadhita International Conference on Buddhist Women in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Approximately a thousand people attended, including about three hundred bhikkhunis from around the world. The rest were Buddhist laywomen. The conference is held every two years. It includes anything that has to do with Buddhist women and supporting them, but, of course, one of the major things that comes up every time is the bhikkhuni order, because it does not exist in every country.

Weren’t you involved in establishing this conference? Yes, I went to the first in 1987, which was held in Bodh Gaya, India. When I got the notification that they were holding it, I thought it was more important to attend than the World Fellowship of Buddhists, because there had never been a conference for Buddhist women before. On the very last day of the conference we were thinking maybe we should make this a more permanent thing. We voted on the name Sakyadhita because it means “daughters of the Buddha.” The Tibetan nun Karma Lekshe Tsomo and I were elected the co-presidents at that time.

What was important about bringing Buddhist women together? First of all, it really opened the eyes of the Tibetan women, because they had no idea that Western women were being ordained as bhikkhunis and there were so many of us Westerners at that particular conference. The Tibetans became very jazzed up, I suppose you could say, by seeing these American women bhikkhunis who took control of their lives. The Tibetan women had never seen anything like that. There are still no bhikkhunis in the Tibetan order. His Holiness the Dalai Lama was there and gave a talk. He was very supportive of the women, and a lot of Tibetan nuns came with him. The conference was held in two languages that year, English and Tibetan.

Which topics were on the agenda at that first conference? The first time we were not so much focused on the bhikkhuni order but rather on how Buddhist women could raise themselves up, because in a lot of the countries Buddhist women still have a very minor role.

The first conference was also the very first time the bhikkhunis there were able to chant the Pratimoksha [the bhikkhuni vows]. It is supposed to be done by every bhikkhu and every bhikkhuni twice a month on half-moon and full-moon days. According to the Vinaya, you have to have at least four members to be able to chant it together, so it was the very first time I’d ever chanted it.

The person who leads it is supposed to be the oldest, so it got left to me to lead the chanting. It begins with the first eight vows. If you break one of these vows, you are automatically expelled from the sangha. I’d chant the first vow and say, “has anybody broken this vow?” and if they hadn’t, they’d remain silent. Every vow of the 348 is mentioned specifically and repeated three times. It took us three hours to get through the whole thing, and I was chanting as fast as I could!

It was a really wonderful experience, that all of these bhikkhunis from all over Europe, Asia, and the U.S. were chanting together. But none of the Tibetan nuns could be included, because none of them had become bhikkhunis.

How has the role of Buddhist women changed from the time of this conference or even from the time you were ordained? Now that you’re thirty-five years in, is it the same? In America, bhikkhus and bhikkhunis are going to be totally equal to each other. At the Soto Zen monastery up at Mount Shasta, two-thirds are women and one-third are men. They call everybody a monk, regardless of what sex they are, and they wear the same robes and they do the same work if they are able.

Thich Nu An Tu is my transmission name, and Dr. Thien-An always wanted me to say Thich Nu, because the “Nu” part after Thich indicates that it’s a female name. I said, “Dr. Thien-An, why do you do that?” He said, “because if I don’t, then nobody will know that you’re a woman!” I didn’t understand at that time what he meant. But now I realize that he was very proud of his women and he wanted people to know that these are bhikkhunis, not just bhikkhus. These are bhikkhunis!

Related: It’s 2020. What’s Happening with Bhikkhuni Ordination?

Do you think the gender equality happening within the American Buddhist community is a reflection of the gender situation in the larger society? I think that has a lot to do with it. Men like to be around liberated women. After Dr. Thien-An died and I became the abbess, I thought most of the men would leave the temple. But they didn’t, and I have more male students than I do female ones. I think men are actually a bit tired of the patriarchy and want to see strong women in leadership roles.

I would like to see the eight special vows for nuns be absolutely thrown out the window!A lot of the American female teachers are highly respected, primarily because we’ve somehow avoided getting into the big controversies that have entangled men. It’s not so much that we’re purer than men, but rather that women are more aware of what can happen if they get involved in some of these things.

Are you referring to the sex scandals? Yes. If you are a master at a temple and someone wants to get at you, they will accuse you of abusing two things: sex and money. And, very frankly, these accusations are not always true. People make up stories. Women are much more careful than men about these things—not that there isn’t plenty of opportunity for it. In fact I’ve been approached by both male and female students.

Really? Yes. When one female student approached me, I just laughed at her. She said, “I’m serious,” and I said, “You think you are, but you’re not really.” A few months later she came to me and said, “Rev. Karuna, I’m so glad that you told me that.” Because by that time she’d found a partner with whom she became involved, and they have a very loving relationship.

This sounds like a very modern, even American situation. How do you find the gender issues you deal with here relate to the gender issues you find when you travel to Buddhist Asia? In the U.S. there is equality. In the rest of the world there is still quite a bit of inequality regarding men and women. When I talk to the Vietnamese monks, I’ll say, “Please make sure the women play the role they should! Encourage them to take a more active role in the temple instead of just cooking and cleaning. Encourage them to become teachers of the dharma.”

Actually, in some Mahayana Asian countries like Taiwan, Hong Kong, Vietnam, and Korea, most of the ordained are female. The Korean women are very strong. Their basic concern is that the big temples are run by men, not by women. My gosh, in most countries around the world bhikkhunis would be glad if that were their biggest problem!

Conservative Sri Lankan monks believe that bhikkhunis must be ordained by other Theravada bhikkhunis. Since there haven’t been any bhikkhunis there for a thousand years, none could be ordained, but there are monks all over Sri Lanka who have quietly been encouraging women to become bhikkhunis for some time. As far as I know, I ordained the very first Sri Lankan bhikkhuni in 1997. Her religious name is Sumentha, but her nickname is Loku Mani, meaning Big Mother, and she runs an orphanage in Sri Lanka. She had been a novice nun for at least twenty years when she came to our temple to visit Dr. Ratanasara and some of the other Sri Lankan monks in residence here. I offered to give her ordination. At first she was unsure, but Ven. Ratanasara convinced her to do it. Now there are almost a thousand bhikkhunis in Sri Lanka, whereas ten years ago there were none.

That’s exciting. Yes, it is quite exciting. In fact, I’ve noticed a change in the Thai people themselves. When I was in Thailand two years ago, it was the very first time that Thai men would come up and bow to me. When they saw the yellow robes they knew exactly what I was, but they didn’t bow before. So the Thai people are changing much faster than the monks, particularly the older monks.

Do you think it’s a question of the old order dying out for bhikkhunis to be accepted in Theravada countries? I think that’s part of it. Once the old order dies out, the younger monks will be able to express their more liberal viewpoint. In fact, that is already starting to happen in Thailand, but it’s going to be a while before it takes hold.

The problem in Thailand is that women can only become Mahayana bhikkhunis. Any woman there who puts on a robe so that she looks like a Theravada bhikkhuni can be arrested and thrown in jail. But Theravada women don’t want to become Mahayana bhikkhunis—they want to be Theravada bhikkhunis.

Isn’t another obstacle for women the extra precepts they must take to be considered fully ordained? What is your opinion of them? I would like to see the eight special vows for nuns be absolutely thrown out the window! The Buddha, in spite of what many people think, did not lay them down. Theravada scholars—both Thai and Sri Lankan—will point out to you that these were not taught by the Buddha. They were added later.

What are the eight special precepts? The first one—probably the most obnoxious to women—is that no matter how old the bhikkhuni is, she has to bow down before a monk who has been a bhikkhu even for one day. That’s probably the most offensive of them. They are rules like that. I teach them to my students, but I explain that these were not originally written down by the Buddha himself.

I don’t remember seeing you do that. Do you bow down to male monks that are younger in dharma years than you? Are you kidding?

***

Buddhism’s Glass Ceiling

The eight controversial vows that women traditionally must take to be a fully ordained member of the Buddhist community:

1. A bhikkhuni, even if she enjoys a seniority of a hundred years in the Order, must worship, welcome with raised clasped hands, and pay respect to a bhikkhu though he may have been a bhikkhu only for a day. This rule is strictly to be adhered to for life.

2. A bhikkhuni must not keep her rains-residence at a place that is not close to the one occupied by bhikkhus. This rule is also to be strictly adhered to for life.

3. Every fortnight a bhikkhuni must do two things: To ask the bhikkhu sangha the day of Uposatha and to approach the bhikkhu sangha for instruction and admonition. This rule is also to be strictly adhered to for life.

4. When the rains-residence period is over, a bhikkhuni must attend the Pavarana ceremony at both the assemblies of bhikkhus and bhikkhunis, in each of which she must invite criticism on what has been seen, what has been heard, or what has been suspected of her. This rule is also to be strictly adhered to for life.

5. A bhikkhuni who has committed a Sanghadisesa offense must undergo penance for a half-month, pakkha manatta, in each assembly of bhikkhus and bhikkhunis. This rule is also to be strictly adhered to for life.

6. A bhikkhuni must arrange for ordination by both the assemblies of bhikkhus and bhikkhunis for a woman novice only after two year’s probationary training under her in the observance of six training practices. This rule is also to be strictly adhered to for life.

7. A bhikkhuni should not revile a bhikkhu for any reason whatsoever. This rule is also to be strictly adhered to for life.

8. Bhikkhunis are prohibited from exhorting or admonishing bhikkhus with effect from today. Bhikkhus should exhort bhikkhunis when and where necessary. This rule is also to be strictly adhered to for life.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.