“Without being imprisoned in Gila Relocation Camp, how would I have become aware of the Buddha’s compassion?”

—An evacuee, in Why Pursue the Buddha? by Gibun Kimura

ON THE EVE of World War II, 12 7,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans lived in the United States. Most lived on the West Coast. Only thirty-seven percent of them were legally “aliens,”or first-generation “Issei.” Seventy thousand others, the second-generation “Nisei” who were born here, were American citizens.

Anti-Japanese sentiment prevailed in this country from the time the first Japanese arrived in 1868. When Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, that racism exploded. Newspapers and politicians fanned the flames of xenophobia, accusing all Japanese and Japanese-Americans of being spies and saboteurs, and calling for their immediate removal from the West Coast. “Herd ’em up, pack ’em off, and give ’em the inside room in the badlands,” wrote San Francisco Examiner columnist Henry McLemore, in January 1942. “Let ’em be pinched, hurt, hungry, and dead against it. . . . Personally, I hate the Japanese.”

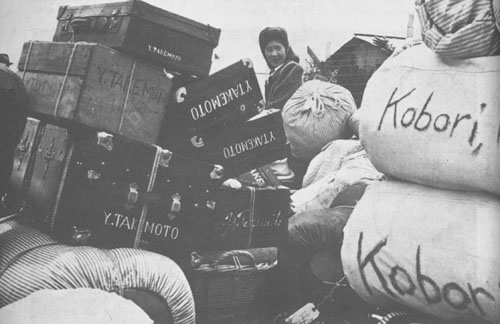

No cases of espionage were ever proven. And many Japanese contributed valiantly to the U.S. war effort. Nevertheless, in the spring of 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, ordering all people of Japanese ancestry in Washington, Oregon, western California, and southern Arizona to evacuate. Altogether, 110,000 people—including fishermen, farmers, old women, and children-were sent to concentration camps in remote areas of the West. Herded like cattle and tagged like parcels, most could bring little more than they could carry. None knew when—or if—they would return.

Fifty years have passed since then. In recent years, calls for reparations have prompted new discussions of the financial, psychological, and sociological impact of internment, but few people have examined the role of religion in the camps. At the time of internment, sixty percent of the internees called themselves Buddhists. The role of Buddhism in the concentration camps and during the years following provides a unique example of the ways in which spirituality can both flourish and flounder in the face of political oppression.

The Challenge

The sudden and violent bursts of anti-Japanese activities following Pearl Harbor shocked and confused Japanese communities all across the West. Many community leaders were detained or jailed immediately after the bombing, under suspicion of being linked to the Japanese emperor. This called into question the loyalties, rights, and futures of Japanese-Americans all across the U.S.

Buddhist ministers were among the first to go. In response, several Jodo Shinshu ministers telephoned the FBI and the Naval Intelligence Bureau in an attempt to define and defend their faith. This core group of ministers also sent directives to local temples, urging their members to support the war effort by buying defense bonds, volunteering for the Red Cross, and giving patriotic lectures. “I was buying war stamps to help the American effort,” recalls Reverend Laverne Sasake, currently of the San Francisco Buddhist Church, then a teenager living in Los Angeles. “Yet my relatives were probably enemy soldiers. It was uncomfortable and confusing, even for a young boy.”

In February 1942, all Japanese and Japanese-Americans were ordered to leave the West Coast. Businesses were boarded up and houses and farmlands abandoned or rented out; personal items were sold or destroyed. The internees’ lives had essentially been erased. “This was a very, very sorrowful time,” says Reverend Julius Goldwater, who at the time was the first of a handful of Western Jodo Shinshu ministers. “No one could understand what was happening.”

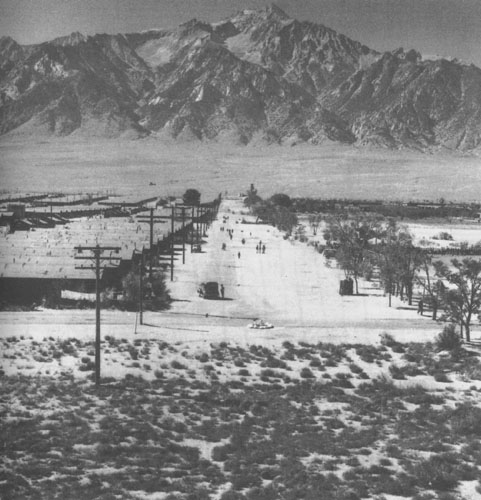

The internees first reported to sixteen assembly centers-many at fairgrounds and racetracks-and were then taken to ten camps across the West and Midwest. Once at the camps, the prisoners were fed and clothed and were allowed some liberties, including attending schools, cultivating gardens, and holding dances, variety shows, and sports events. But the shock of internment cannot be underestimated. Many of the internees were told that this was for their own good, that they were being protected from hostile Americans. Yet whole families had been transplanted from their familiar communities and homes to inhospitable landscapes, where they were crowded into small barracks made of plywood and tar paper, furnished only with cots and potbellied stoves. Other furniture had to be fashioned from scrap lumber. Evacuees had to stand in line for the bathrooms and showers, and were given only mess hall food. “The deprivations were appalling,” recalls Reverend Goldwater, now in his eighties.

Surrounded by barbed wire, watchtowers, and armed guards, many were unsure when they would return or what lives would be left. “We were told this was to keep the Japanese community secure,” says Reverend Sasake. “But we were deprived of everything, all our basic rights.”

“It Cannot Be Helped”

For many prisoners, social support provided by Buddhist churches helped alleviate the unpleasant conditions. Eighty percent of the Buddhists in the camps were affiliated with the Jodo Shinshu (Pure Land) sect. Although more than half of that sect’s ministers had been taken to the Poston, Arizona, camp early on, those remaining did their best to serve the needs of the evacuees both during relocation and at the camps. Sometimes the aid was quite simple. One minister in the Minidoka, Idaho, camp simply kept repeating, “shikata ga nai,” or “it cannot be helped. “

Internees were allowed to conduct Buddhist ceremonies from the very start. At the Tule Lake camp, for example, Sunday school services were held for young people, and evening services were held for adults—in addition to the usual weddings, funerals, and religious commemorations. “My home was a church in Tule Lake,” recalls Reverend Sasake, whose father—and twenty-five fathers before that—was a Jodo Shinshu minister. “The parlor of our barrack became a temple.”

But ceremonies suffered constraints. One early problem was that the Wartime Civil Control Authority (WCCA) had designated English as the official language at the camps. Yet many ministers and the Issei spoke only Japanese, and few Nisei ministers spoke fluent English. Only later, when WCCA authorities really understood that many Issei could not understand English, did they allow the services to be conducted in Japanese.

Even then, recalls Arthur Takemoto, now a retired minister in San Diego, some Buddhists were wary. “Many Japanese had been interned because they taught the language, or because they were involved in Japanese cultural arts,” he recalls. “To avoid being mistaken, we would conduct our ceremonies in English. That way the guards always knew what we were doing.” In addition, few Japanese had been allowed to bring religious items into the camps. Others destroyed or hid items regarded as incriminating, including sutra books and Buddhist altars.

To overcome the language barrier, many ministers and assistants used alternative teaching methods like storyboards and puppets. And in response to the lack of Buddhist articles in some camps, people carved Buddha statues and shrines from scrap wood and sagebrush found in the desert. At the North Dakota camp, Arthur Yamabe, who later became a minister, once carved a figure of baby Buddha from a carrot.

Where several denominations coexisted, the ministers sometimes made compromises to care for all needs. In the Poston camp, for instance, priests of the Shingon, Nichiren, and North American Buddhist Mission sponsored joint services. And instead of reciting “Namu Amida Butsu” (I rely upon the Buddha of infinite Light and Life) or “Namu Myoho Renge Kyo” (I rely upon the marvelous Lotus Sutra), the priests agreed on“Namu Butsu,” or simply “I honor the Buddha.”

Unlike the Japanese Christians, the Buddhists could call on little outside help. One key exception was Julius Goldwater, who at the time was the only Caucasian Jodo Shinshu priest in all of America. Throughout the war years he drove to each camp, visiting people, holding gatherings, and donating altars and beads. “I would bring them coffee, fine chocolates, literature,” he says. “Sometimes I brought nuns or monks from Sri Lanka to help teach. That was like a three-ring circus. Most Japanese had never seen monks in yellow robes. They thought they were clowns. But it ended up being very revelatory and fulfilling to them.”

When asked if he addressed the conditions of internment in his sermons, Reverend Goldwater said, “Certainly not. I ignored the evacuation. The point was to transcend the present condition.”

Buddhism Under Pressure

Many internees, however, found the evacuation to be central to their practice. One, Reverend Fujimora, wrote, “If I did not have the Nembutsu to support me then, how difficult it would have been for me—how alone I would have felt. But because I had the Nembutsu, I was able to survive, and to be cultivated.” Similarly, in one sermon, Reverend Gibun Kimura, an Issei minister in Salinas who was held in both the Turlock and Gila River camps, told his congregation, “Having lost all our possessions and living a camp life where we no longer need to be concerned with the day-to-day task of making enough to eat, isn’t this a splendid time to settle down and truly become aware of the teachings of Buddha-dharma?”

Reverend Takemoto, who was a student at the time, claims today that Buddhist faith helped many thousands get through the camp experience. “Understanding the basic tenets of Buddhism orients people to understand the reality of life, that things don’t go the way we want them to go,” he says. “This becomesdukkha, suffering and pain. To be able to accept a situation as it is means we could tolerate it more. We couldn’t change it.” Indeed, the camp experience spurred Takemoto to become a minister. “I had been raised as a Buddhist from a very young age,” he says. “Then I was asked to assist in the ceremonies, to be a youth director. I realized then how ignorant I was of my own religion.”

Reverend Sasake believes that the experience deepened people’s faith through gyaku-en, or reverse conditions and causes. “This is growth and understanding through negative or bitter experiences,” he explains, rather than through jun-en, or regular conditions and causes, like formal study. “One can grow in difficult situations,” he says. “Buddhists can capitalize on any experience.”

It would be a mistake, however, to assume that all Buddhists in the camps grew from the experience or that all internees had a spiritual awakening. “I think many of the Buddhists there had a very shaky foundation in the dharma,” comments Goldwater. “It was merely habitual, a point of ethnic pride. When that faith was challenged, the people were bereft; they were set adrift. Once the elegance of their heritage and culture were stripped away, they found themselves to be just ordinary people. They didn’t necessarily grow.”

In addition, many sources recall, some internees were hesitant to appear “Buddhist” because of its affiliation with Japanese culture. “It didn’t dawn on me until about midway through the process that they held this concept,” Goldwater says, “but many of the internees believed that Buddhism was particularly Japanese, and that to be Buddhist was disloyal.” The aftermath of bitterness has also cast its poison, he notes. “As with any culture, there are varying degrees of civilized awareness and understanding. Some people have fallen prey to a more narrow worldview, to a strong bitterness.”

Thus Have I Heard

While Zen practitioners were very much the minority in the camps, some of the most moving accounts of the ability to translate adversity into spiritual challenges can be found in their accounts and poetry. In his history of American Buddhism, When the Swans Came to the Lake, Rick Fields has noted that when Zen Master Sokei-an was taken to an internment camp, he carved a walking stick with a dragon emblem and presented it to the colonel in charge. In later years, he would tell his students that “by fighting, one gets to know each other.” Zen Master Nyogen Senzaki, who had been living in the States since 1906, expressed similar equanimity during his internment. Senzaki wrote a farewell poem to the Los Angeles Zen Center before leaving for Heart Mountain, a camp in Wyoming, where he lived for more than three years:

Thus have I heard

The Army ordered

All Japanese faces to be evacuated

From the city of Los Angeles

This homeless monk has nothing but a Japanese face.

He stayed here 13 springs

Meditating with all faces From all parts of the world,

And studied the teaching of Buddha with them.

Wherever he goes, he may form other groups

Inviting friends of all faces,

Beckoning them with the empty hands of zen.

In Namu Dai Bosa, which charts the transmission of Zen to America, editor Louis Nordstrom has noted that by using the classic sutra opening, “Thus have I heard,” Senzaki treated the government order as a holy scripture. Equally clear is Senzaki’s perception of the internment experience as a chance to practice and spread the dharma. Nordstrom writes that Senzaki insisted on calling Heart Mountain the “Mountain of Compassion,” and named his zendo—where several students regularly came to sit “Tozen Zenkutsu,” or “Meditation Hall of Eastbound Teaching,” since Wyoming was east of California. Indeed a later poem predicted that the concentration camps would push Buddhism further toward the Atlantic:

This morning, the winding train,

like a big black snake,

Takes us away as far as Wyoming.

The current of buddhist thought

always runs eastward.

This policy may support the

tenacity of the teaching.

Who knows?

After the War

Starting in 1944, the U.S. Government began allowing internees who pledged their loyalty to America to resettle in areas beyond the strategic military zones along the West Coast. Resettlement, however, was not easy. “It was especially bad for the first generation,” says Takemoto. “Many of these people were at the prime of their life, and they had to start all over again, from nothing. This was most disheartening.” The Nisei too, suffered. Although many came back determined to make up for lost time, and prove that they too could be productive Americans, many were anxious to shed the last vestiges of their culture.

Effects on Buddhism in America, however, were primarily positive. As Senzaki predicted, the camps did force yet another eastward spread of Buddhism. By 1944, thousands of evacuees had landed in Midwestern and Eastern states, creating pockets of Japanese-American populations, all of which needed temples and active ministries to create strong social ties and ease the transition back into American life. Many temples began as just small gatherings with lay speakers, and only later grew to inhabit permanent buildings.

In the beginning, most Buddhist groups had to report regularly to the FBI. Because he spoke English, Reverend Takemoto became the liaison to the FBI in Chicago, when he helped set up the Midwest Buddhist temple. “I reported weekly,” he says laughing. “By the end of that time, the FBI agent and I had become very good friends.”

In addition, the relocation spurred several attempts to make Buddhism more readily understandable to Americans. The earliest such attempt occurred in the early forties, when a nonsectarian organization called the Buddhist Brotherhood of America, led by Reverend Goldwater, tried to create an “American Buddhism,” combining Mahayana and Hinayana traditions, that could garner popular support. This effort was supported several years later by the Young Buddhist Association, a predominantly Nisei organization formed for the English-speaking children of Japanese immigrants, who wished to create a specifically American Buddhism and eradicate the cultural associations with Japan.

Efforts to “sanitize” the religion went even further in the later years of the war, as the Buddhist Churches of America agreed to renounce ties with Japan and subdue ties with the Jodo Shinshu religious headquarters in Kyoto, to fill all offices with Nisei, with Issei acting only as advisory boards, and to make English the predominant language.

Few of these changes took place immediately, as it took time both for the Issei to leave office and for Nisei to translate Buddhist materials. Nevertheless, the internment and aftermath created many opportunities for the Nisei to get involved in church hierarchy, where only the Issei had held sway earlier. The Institute for Buddhist Studies was created after the war specifically to train English-speaking ministers. “The need for English-speaking ministers provided opportunities for young people to have their own gatherings,” Takemoto says now. “These were the beginnings of English gatherings.”

One of the most symbolic gestures of this period was the abandonment of the sauvastika, the centuries-old Indian symbol for Buddhism that closely resembles the swastika, adopted by the Nazis. Because of the confusion, many churches began emphasizing instead the Wheel of Life or the Eightfold Noble Path symbol. “1 still remember knocking the old symbol off the Sacramento Buddhist church,” Reverend Sasake says. “I can’t remember if we were told to do it or if we volunteered, but I remember it falling to the ground.”

Humpty Dumpty

On July 2, 1945, the Supreme Court ruled against any further restriction of people of Japanese ancestry, and the full process of release began. Forty-three years later, the U.S. Congress finally passed a law promising $20,000 to each of the 75,000 remaining victims of internment—a small amount for years of pain and fear. But, as Goldwater has noted, the internment and subsequent release helped smash remaining antiJapanese legislation in this country. And the experience of the internees itself reveals the infinite possibiltity of converting adversity into opportunity. As Senzaki wrote:

Nothing changes Humpty

Dumpty.He has the spirit of

Bodhidharma.He never stays down.

He always rebounds to his

upright position.The world of desires, the world

of material and nonmaterial

existence are merely different

phases of Mind-Essence.Manusya, the human beings, and

Asura, the fighting devils, are

neighbors to one another.Both are on their way of progress

toward the Great Peace.Even though wise beings build

and stupid destroy—as

children play—the spirit of

Humpty Dumpty goes on and

on, just the same.Cannot everyone see the blue

waters of the Pacific Ocean,

which neither increase or

decrease?

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.