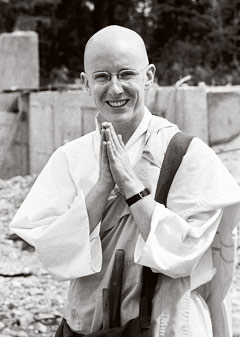

Sister Clare Carter seems like other kindly Buddhist nuns I’ve encountered along the way, just not quite. Her face and manner are warm and open as she welcomes the peace activist Paula Green and me into the old converted barn she shares with two monks and uncounted squirrels in Leverett, Massachusetts. She talks with Green, a friend who lives nearby, and me about this and that in an endearing Boston accent that makes me wonder whether she might have joined one of the Catholic orders dedicated to service had her life unfolded differently. There isn’t a nanosecond of awkwardness or unfriendliness, no hint of the gap between her life and mine. What I’m noticing, I think, is the mindful formality that isn’t there.

Over a cup of tea at her house before we came here, Green told me to expect kindness. “They are very humble and embracing of others,” Green said of Sister Clare and the other two members of this outpost of the Nipponzan Myohoji, a small and little-known sect of Nichiren Buddhism. “There is tremendous selflessness, which is very moving,” Green said. “There is no pushing people to do this or believe that.”

Green told me she’d gotten to know Sister Clare and her brother monks in 1983, when they moved onto donated land to build the first Peace Pagoda in North America. Back then she was so impressed by the gentle, nonconfrontational way the head monk dealt with initial opposition in the surrounding community that she invited the tiny order to sleep on her floor while they got the barn ready and cleared land.

“I was very drawn to their commitment to peace and the abolition of nuclear weapons, to their vows of poverty and simplicity, and to their very strong political beliefs in social change,” she said. Admitting that their practice of chanting and drumming doesn’t take her as deeply as the Vipassana, or insight, meditation she practices, Green credited the monks with getting her going in her own peace work by showing her what serious commitment looks like.

As Green says goodbye to Sister Clare to head off to the airport and her own kind of peace work, I note the offerings stacked around a dimly lit room: boxes of Annie’s Macaroni and Cheese, jars of peanut butter, protein bars. In his collection of dharma talks, Tranquil Is This Realm of Mine, Nichidatsu Fujii, the sect’s Japanese founder (who died in 1985 at 100) writes, “Those who are successful at Nipponzan are those who do not mind a life in poverty, for whom food is not an issue.” What to have for dinner was clearly not a big subject of debate here.

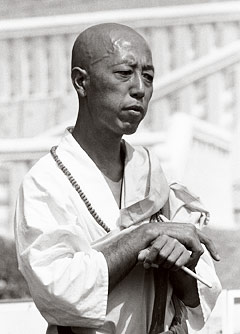

Ordained as a monk at nineteen years old, Fujii became an ardent disciple of the 13th-century Japanese sage Nichiren, who taught his followers that they could realize the whole of the Buddha’s teachings by chanting thedaimoku, the seven syllables of the title of the Lotus Sutra—or more precisely, “Veneration to the Sutra of the Lotus of the Wonderful Law”—Namu-myoho-renge-kyo.

By 1917, Guruji, as Fujii was commonly know, had committed himself to a path of total nonviolence. His life’s mission would be spreading peace by walking the world beating a hand-held drum and chanting the daimoku. When the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima— on August 6, 1945, his 60th birthday—the horrific event supercharged Guruji’s mission to bring peace to the world, and he directed his focus to removing nuclear weapons. He urged his monks and nuns not to chant for personal happiness but to consider the chant big medicine “meant to be spread through the world to quench the flames of modern warfare.”

Guruji’s hard monastic practice is not the way of the Soka Gakkai, a more popular form of Nichiren Buddhism. [For more on the Soka Gakkai, see the interview with Daisaku Ikeda, “Faith in Revolution.”]

They are up by 5:00 a.m. every day, circumambulating their Peace Pagoda in all weather, performing hours of rituals in addition to attending to every detail of their physical property and their lives. They spend months every year walking the globe, beating their drums and chanting. Sister Clare has walked from this place to South Africa, and this past winter the nun, who is in her late fifties, walked from here to Washington, D.C., then from Hiroshima to Tokyo, protesting a movement to remilitarize Japan.

“They walk twenty miles a day at a fast pace and sleep in basements, in churches, wherever they can,” Green had told me. “They walk their talk, literally.”

The name “Guruji” came from Mahatma Gandhi, whom Nichidatsu met in 1933 while fulfilling a vow to bring the “Supreme Dharma” (“Myoho”) back to India from Japan. As for Gandhi, according to a granddaughter, Sumitra G. Kulkarni, the great Indian leader took up Guruji’s drum and made the daimoku part of his ashram’s morning and evening prayers.

SISTER CLARE leads me through the woods toward the Peace Pagoda. We talk a little. Even though I know she is not walking fast by her standards, the judgment pops up that she is too quick and light. I realize the pace and the friendly patter is jostling against a memory I have of walking next to the Zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh during a weeklong retreat in upstate New York. The Vietnamese Zen teacher had glided along silently and slowly, as if he were on rails. He seemed very concentrated, literally, like he was made of some super-dense material so that he could not be moved.

This had become my image of what it takes to be a Buddhist peace activist, I realize. A person had to work a long time to acquire inner stillness and solidity and unshakable awareness so he or she can walk on through any kind of conditions, no matter how harsh or frightening. Yet Guruji and Sister Clare and her fellow monks and nuns had done just this. But by what power?

“It is with our capacity of smiling, breathing, and being peace that we can make peace,” teaches Thich Nhat Hanh in Being Peace. This had sounded like baby talk before, but the day I walked next to him, I understood. A person had to “be peace,” to have “sovereignty” over herself, to breathe and move with conscious awareness, before she could make peace.

Like Thich Nhat Hanh, Nichidatsu Fujii had witnessed the calamity of war. But he had no faith in any kind of personal meditation techniques to stop it. He had faith in the Lotus Sutra, the vast and mysterious scripture that scholars believe was composed in the first or second century C.E. More specifically, he had faith in Nichiren, who taught that for our “Era of the Declining Dharma” the Buddha packed the vast and mysterious vision of the Lotus Sutra—and of the whole dharma—into a single phrase.

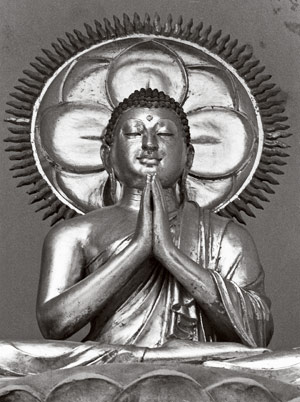

According to legend, Shakyamuni Buddha preached the Lotus Sutra at Vulture Peak, in northern India. Scholars, noting its repeated exhortations to have faith and devotion in the sutra itself, have described it as “a lengthy preface without a book.” To believers, however, it is literally the last word in Buddhism, revealing that the historical Buddha is a force of wisdom and compassion that is eternal and present everywhere and in all beings.

Nichiren did not invent the practice of repeating this phrase to express devotion or praise, but he was the first to define it as the only practice for the direct realization of Buddhahood in our time. He taught his followers to live their faith inwardly and outwardly, to speak truth to power, to “read” the Lotus Sutra not with the mind but with their hearts and bodies, their whole inner and outer lives.

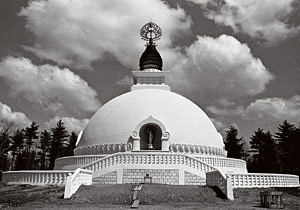

Walking with Sister Clare in the woods, I am sensing the gap between slow and stately “progress” Buddhism and that which hinges on the leap of faith. As we approach the Peace Pagoda, Sister Clare stops talking to me. She begins to beat her well-worn handheld drum and chant: Namu-myoho-renge-kyo. The pagoda looms up 75 feet in a clearing in the woods. Gleaming white and gold, it looks like it alighted here from space.

Guruji began encouraging the building of stupas in 1945, heeding this exhortation from the Lotus Sutra: “After the Buddhas have passed into extinction, if persons make offerings to the relics, raising ten thousand or a million kinds of towers… then persons such as these have all attained the Buddha way.”

Sister Clare bows before the pagoda, explaining that there are relics inside it that were given to Guruji in Sri Lanka. It was built entirely by them with the help of volunteer labor, which the order attracts without asking. “No matter how grand the Dharma-work, Nipponzan will absolutely not solicit contributions based on quotas,” said Guruji in Tranquil Is This Realm of Mine. If there is not enough money, “simply suspend the construction.”

We begin walking around the pagoda counterclockwise instead of the clockwise direction Sister Clare and her brother monks walk chanting every day, so that we can see in chronological order the four statues carved in relief in the base of the statue that represent the life of Buddha. Three men join us. Sister Clare asks the men how they found the place. They tell us they saw the pagoda on a local news show in Boston and felt compelled to come here. One man, Ernie, tells us he visited some Buddhist temples in Japan and Korea when he was a soldier stationed there during the Korean War.

At the mention of the Korean War, Sister Clare softly chants: Namu-myoho-renge-kyo. I’ve noticed that she chants at the end of phone conversations and after references to violence or suffering or acts of compassion and hope, the way a Catholic nun might say “Lord have mercy” or “God bless you.” Later, I would learn that she was invoking the teachings of the thousands of Buddhas. She was transforming the very spot where she stood into the dharma realm.

In her brilliant scholarly study Original Enlightenment and the Transformation of Medieval Japanese Buddhism, the Princeton professor of religion Jacqueline Stone writes that for Nichiren “the daimoku contains, or rather is, the entirety of the dharma realm.” Chanting the daimoku with the mind of faith contains all teachings and all the merit of all the good practices of all the Buddhas. It embraces all phenomena—“three thousand realms in one thought moment, the entirety of all that is.”

According to Stone, Nichiren taught his followers in the strife-torn Kamakura period that the Buddha held out this special single practice, this Lotus that bloomed and bore fruit at the same time, for a dark age. Enlightenment is realized in the moment of practice, and it depends “on one condition only—faith in the Lotus Sutra, which is inseparable from the chanting of the daimoku. Anyone who chants the daimoku, man or woman, cleric or layperson, foolish or wise, realizes enlightenment.”

Sister Clare, the men from Boston, and I all go look at a new temple that is slowly being built next to the pagoda. One man says he will send his son, who does heavy construction in Boston, to take a look and possibly help. Outside the temple, as Sister Clare goes around back and locks up, the men make pleasant conversation. One man tells me he is Catholic, another Unitarian. They ask me if I am Buddhist. I tell them I practice Buddhist mindfulness meditation.

I think of adding that I practice “neural Buddhism.” Weeks before, on May 13, 2008, the conservative columnist David Brooks had published an op-ed column called “The Neural Buddhists” in the New York Times. Thanks to a new wave of brain research in the past several years, Brooks told the vast Times readership, the major insights of the Buddha are now on their way to becoming established scientific fact. Experiments are proving that there is no fixed self, that we are an ever-updating process of ever-changing relationships. Brooks also reported that there is growing evidence of an instinctive morality and an innate potential for a transcendent experience. Standing in front of this temple with these men, I realize that I don’t think of myself as practicing a religion when I meditate. I think of myself as practicing reality. A friend calls the excitement about such research “Buddhist Triumphalism.” It is beginning to dawn on me that I believe that my scientifically validated, New York Times–approved Buddhism is the last word, the one true and essential Buddhism.

SISTER CLARE comes back around, beaming, shaved head gleaming in the sun. Standing there in the same bright light, I’m aware that I am captive to a particular, history-dependent point of view.

Buddhist modernism is a scholarly term that “refers to a style of representing Buddhism as rational, empirical, and dismissive of ritual, faith, prayer, and what to the modern mind might be seen as superstition,” said Jacqueline Stone in an interview in this magazine in 2006. Buddhism has always adapted to the demands of time and place. Indeed, Nichiren presented his single practice in response to a chaotic time. Still, confronting this other way of being Buddhist, a way that clearly has borne fruit in the sense of producing a compassionate person living an altruistic life, it strikes me that I must acknowledge and accept the limited and dependent nature of my own Buddhist modernist view as part of my practice.

I wonder, though, if I’m not actually a Buddhist postmodernist. After all, Buddhist modernism began in the late nineteenth century, as a way of presenting the dharma as an alternative to Christian faith, which didn’t seem to fit the scientific-rational worldview. Yet in the face of Sister Clare’s devotion to her singular practice, my approach feels eclectic and self-oriented. I didn’t mind engaging in a few faith elements, initiations, red strings, and the like so long as the focus stayed squarely on my own development, my own eventual realization.

Here with this kind, austere woman, however, I am aware how often I am blind to the true scale of Buddhism— and of the world—taking a little of this and a little of that, telling myself this is fine because there is but one dharma in the end. I still believe this, that the dharma is a way of seeking the oneness of reality and that my somewhat fitful practice helps me open to it over time. But I feel a little bit like one of those yards at Christmas where toy soldiers guard Baby Jesus while Santa Claus and his electric reindeer look on. I take figures and practices out of historical context, as I need them, while Sister Clare focuses on the cosmic ground. She dwells in the vast floating world of the Lotus Sutra—no wonder she seems light.

Back at the barn, we go upstairs to an altar with a statue of Nichiren and a picture of Nichidatsu Fujii looking radiant. Sister Clare introduces me to Brother Kato Shonin, who kneels in the back of the room, working at a low table. He bows. Sister Clare and I kneel together at the altar, and Sister Clare chants for her teachers and for the whole world. Afterward, we go back downstairs and settle at a kitchen table, where we sip tea and I get to ask her how a nice Irish Catholic girl from Boston wound up on a path like this.

“I met Kato Shonin in Boston in 1977, in the midst of a three-day, three-night vigil for Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” she says. “Ten minutes before the end, this Buddhist monk appeared with a drum, chanting. I felt this incredible connection. It was clear to me that this was the most important thing that had ever happened in my life.”

She found out that Kato Shonin chanted every morning somewhere in Boston, and chanted with him. “For me, this prayer and going to this little place in Boston and praying, there was a sense of no reservation, the deepest sense of trust and of giving.”

On June 12, 1982, almost 25 years exactly before the day we sat talking at that scarred wooden table, approximately a million people gathered on the Great Lawn in Central Park in New York City, demonstrating against nuclear arms and for an end to the arms race of the Cold War. It was the largest antinuclear demonstration—the largest political demonstration—in American history, before or since. I was there, and so was Sister Clare.

“Wasn’t that a sight?” I add. “A sea of humanity all gathered so peacefully.”

“Oh my God, it was incredible. It was like all of New York just transformed into this Pure Land. I remember the police. It was like they were relieved of this burden they carry, these layers of distress and duress. Everyone was together that day, that’s my memory. It was entirely wondrous.”

Nichiren taught that the Pure Land, or Buddha Land, was not only to be realized subjectively in the moment of practice but manifested in actuality. You have to walk it like you talk it.

“I remembering seeing you,” I said, meaning I remembered how her order really stood out, the orange and white robes, the drums and chanting. “I don’t suppose you remember seeing me.” She smiled.

“And Guruji was there, and he had enormous energy,” said Sister Clare. “He felt that it was so important. Actually, our order did five walks throughout the United States leading up to that one in Manhattan. That was magnificent.”

I ask her how far she has walked and chanted for peace.

“The longest walk was a little over a year, walking from here down the East Coast to the Caribbean and then through West Africa into South Africa. It was called the Interfaith Pilgrimage of the Middle Passage, retracing the journey of the slave route. That was in 1998 and 1999.”

“The longest walk was a little over a year, walking from here down the East Coast to the Caribbean and then through West Africa into South Africa. It was called the Interfaith Pilgrimage of the Middle Passage, retracing the journey of the slave route. That was in 1998 and 1999.”

She explains that they walk through the winter. In January and February, she and her fellow monks walked from Boston to Washington; from mid-February until early May, they walked in Japan, protesting a movement to repeal the constitutional ban on war and the maintenance of military forces.

“Seven thousand local people walked with us to protest,” she said smiling. “No unions, no organizing, just folks. The power from the spirit of the people was just shimmering.”

The poor surroundings, the hidden majesty of the practice, remind me of the Pali legend of the death of the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni. At the end, ill and in pain, he walked northward, away from the famous cities where he had lived and taught for the previous 45 years, through more and more obscure villages until he came to Kusinara. There were no more crowds, no kings or brahmins, no great numbers of noble disciples crowded around him in the end.

According to Karen Armstrong’s biography Buddha, Shakyamuni’s attendant monk Ananda broke down in tears and asked his master why he had to die in this rough outpost. Why not go back to the city and be surrounded by followers? Why be almost alone? Armstrong speculates that the Buddha had always to be pressing forward “to bring help to the wider world.” I think of the path Guruji laid out for his disciples, a way that could never be for the many, turning their backs on fame and status to bring the healing power of the Buddha to the world. It strikes me that the Buddha’s moving away from the known world into the unknown may have been another way of imparting what is so lavishly portrayed in the Lotus Sutra: The Buddha is everywhere, and enlightenment might happen anywhere.

AS NICHIREN HIMSELF felt in his own time, the monks and nuns of Nipponzan Myohoji are inspired by a sense of urgency about the world’s suffering. They are also inspired by each other. “We are a very small order,” says Sister Clare, “and many monks and nuns either practice alone, or maybe with one other, so we have to support one another. We’re around ten or eleven in this country.”

Sitting there in an old room permeated with a damp chill in spite of the bright day outside, I think this is like The Last of the Mohicans. There are only a few hundred Nipponzan Myohoji left in the world, and they aren’t getting any younger. The head monk, Brother Kato Shonin, is now sixty-eight years old.

I know that I am not cut out to be one of them, that this path would be barren for me. The leap of faith it requires is so lacking in concern with inner experience, so dependent on being able to embrace the Lotus totally and at once with the body, heart, and mind, that I would probably lose my way. The majority of contemporary people, I guess, need a practice based on and enlivened by mindfulness or they would be liable to succumb to arrogance or pride or despair or all the other delusions and desires.

Sister Clare agrees that in Guruji’s presence and in his teaching there was “almost no reference to personal development. It was about the interconnected wholeness of all of us and realizing this Pure Land together.”

In the contrast of styles, between the meditation-oriented Buddhism I’ve been raised in and the faith-inspired Buddhism I’m now encountering, I see something about each more clearly. Spirituality without any emphasis on self-knowledge can become unbalanced, I fear, leading to sheer ascetic mastery or blind belief. Yet a spirituality that is weighted in the direction of the inner life can sink into mere narcissism.

“We want people to feel really encouraged, not judged,” says Sister Clare. “We need to connect more with each other and with our own hearts, as simple as that sounds.”

After the interview is over, Sister Clare walks me a ways toward my car. We talk about the upcoming presidential election and our hopes for peace, parting with a smile and a bow. Months later when the weather turns cold, I find myself thinking of her and her small order threading their way through the world, connecting us to the infinite and eternal with their practice, reminding us there is a truth that is always beyond the power of words.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.