I am an older Black Buddhist practitioner. Throughout the three-week trial of former police officer Derek Chauvin, I watched and experienced holding tension between the past and desire. During this time, I engaged in a practice I call “shock protection”—noticing that the fact our conditioning may not have prepared us to receive what is to come while trying to remain neutral as a way to lessen the pain of another unjust outcome.

Buddhism is founded on shock protection if we take into consideration that the Buddha was conditioned to not see human frailty while he remained in his wealthy province preparing to inherit his father’s powerful position. Some of us have been conditioned in this way—we have been beneficiaries of the rule of law, but many others of us have not. Shock protection is another way of practicing equanimity, but an equanimity fueled with decades of disappointment for the hundreds of millions of black people killed in the US over 400 years of slavery, Jim Crow, lynching, white supremacist-crafted criminal justice systems, and mass incarceration. It would have been foolish of me to cast this history aside while watching the trial, as the defense “retried” the case during closing arguments using the playbook other attorneys have used to defend white police officers who killed unarmed Black men. This playbook has included repeatedly reminding jurors of the deceased’s character imperfections, past criminal behaviors irrelevant to the case at hand, imperviousness to pain, underlying medical conditions and the police’s perceptions of the deceased as innately dangerous due to appearance (including inferences to the deceased being Black), along with a host of other strategies to dehumanize someone who is already dead. To counter this playbook, the prosecution needed to resort to reminding the jurors that George Floyd had parents who brought them into the world, using Floyd’s birth certificate as proof! Keeping this history in mind, I wasn’t angry, or in shock. I was reminded that this is how it has been, and it has worked in the past to convince jurors that they did not see what they saw. I’m very familiar with the cognitive impact of being invited to doubt my beliefs.

As a Buddhist practitioner, I’ve been taught and trained to question my perceptions. This is useful for lessening the suffering that comes from clinging to views that become narrower the more I cling. Some Buddhists refer to this as a wholesome form of doubt. But when the defense in the Chauvin case said in their closing arguments that jurors should doubt the evidence presented by the state about the causes of Floyd’s death, was that the same as training jurors in cultivating Buddha mind? I don’t think so, largely because so much was riding on their doubt—namely, the maintenance of and justification for the deadly use of police force remaining situated in police discretion alone. In Buddhism, our trainings and teachings in doubt are about expanding our awareness. On the other hand, the defense was arguing for the very same thing—broadening the jurors’ awareness.

Those of us who saw the viral videos saw Chauvin kneeling on Floyd’s neck for what we initially thought was 8 minutes and 46 seconds, but what turned out to actually be 9 minutes and 29 seconds. What does this mean? Collectively, we were wrong. There was nearly another minute of factual information from the police officers’ vantage points; it means that we missed facts by only having access to the viral videos taken by witnesses. This was part of the defense’s argument. The other part of their argument was that the jury had to make a decision about what a “reasonable police officer” in that particular situation would do. Contrary to what the Minneapolis police officers testified to regarding their practices not being consistent with Chauvin’s actions, the defense argued, with supporting evidence, that police have a multitude of decisions to make and each action of the arrestee is cause for a new set of decisions. The defense also said that the police officer is not required to believe anything the arrestee is saying about how they feel. In defense attorney Eric Nelson’s view, it didn’t matter that Floyd said he was claustrophobic. It didn’t matter that he said the handcuffs hurt (in fact Floyd’s wrists were bleeding), it didn’t matter that Floyd said he couldn’t breathe, it didn’t matter that Floyd was lying face down in the prone position (because he was able to talk), and it didn’t matter that Floyd became unconscious because each of these factors (according to the defense) were changeable.

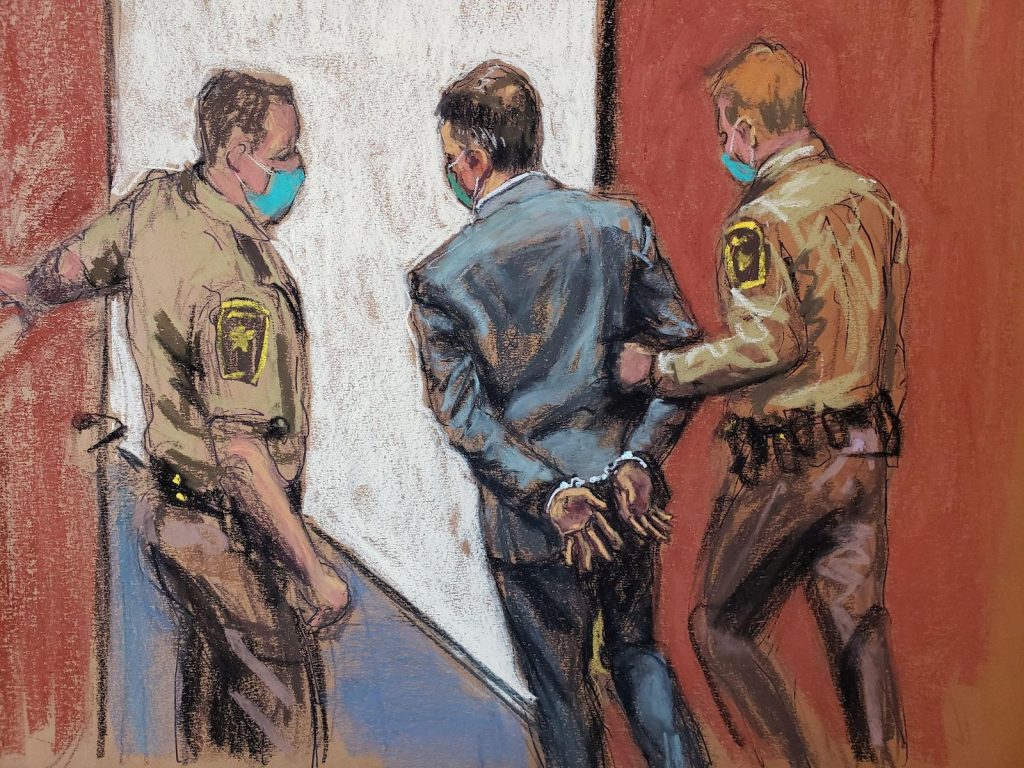

Buddhists have also been taught about changeability. We call it impermanence. The impermanence we are taught about has to do with not clinging to things that have no permanence—even ourselves—so that we do not become deluded and then distraught when we must inevitably part from everything we love as we are reminded in the five remembrances (through death and natural processes of loss that are part of any human life). The defense’s “impermanence” argument was different altogether. The defense argued that even when Floyd was not resisting, he could resist again, thereby justifying the length of time Chauvin had his knee on Floyd’s neck. We may not agree with the defense, but we know from our own teachings in doubt and impermanence that if these teachings are not grounded in the ethics of non-harm, compassion, selflessness, and truth, they can be twisted toward supporting injustice. Many Buddhists have supported injustice with indifference by not coming together as one entity, focusing on anti-Black racism. It is a political choice. What is a Buddhist to do now that Chauvin has been found guilty and the three other arresting police officers are scheduled for trial in August?

Though cities across the US, including Minneapolis, prepared for a violent response if Chauvin was acquitted, Buddhists were not prepared to stem the energetic flow of possible violent responses because we haven’t been able to harness the power we have to effectuate structural change. Still, it is not too late to find our collective voice in areas of racial justice. As we contemplate this historic guilty verdict, we can also endeavor to engage police departments across this nation on this question: How can we support you to trust that those you arrest are in pain when they say they are? We say we are students of the Four Noble Truths, and we dedicate the merit to all sentient beings, but do we, as American Buddhists, take the time to understand the suffering that is caused by the school-to-prison pipeline that includes miseducation, policing, the court systems, and mass incarceration, and seek to collectively transform this situation? Do we take that understanding to those who cause suffering, and proclaim the third noble truth—that things can change? What within the noble eightfold path can we apply to the transformation of modern-day lynchings and slavery? Let’s examine what right action means in this context.

Maybe we’ve been too immersed in our doubt and teachings in impermanence to be moved off our proverbial cushions to be the agents of change we chant in our bodhisattva vows. I think we’re more prone to magical thinking than we want to admit. Meditation, learning, and chanting alone will not stem the tide of racism, murder, and imprisonment. Nor will they stem the tide of an ever-increasing militarized police force. I often hear Buddhist practitioners say, “I don’t know what to do.” Do our practices actually serve to disempower us? Do they cloud our perceptions when we say we are expanding our awareness? We need to take a deep look at what we’re learning and practicing, otherwise we unwittingly run the risk of solidifying being agents of white supremacy.

With the new reality that a white police officer can be found guilty of murdering an unarmed Black man, how will we interpret this reality for what our lives mean and can mean? How do predominantly white sanghas make room for Black and Brown people living with an existential situation that hasn’t changed just yet? By practicing deeply with racial and cultural humility. But that’s not all. Even if Chauvin had been acquitted, sanghas need to come together, harness our power, and deploy the positive power of our practices in compassion, directing that power to the policing of our neighbors and fellow citizens. We can begin with just one goal, restoring the humanity of arrestees who cry out that they are in pain, so that police officers will also care for those they are arresting.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.