This episode of the life of Shakyamuni Buddha, as retold by Nikkyo Niwano, starts in Bodh-gaya following the Buddha’s enlightenment under the Bodhi tree. The decision to turn the dharma wheel initiates a teaching mission that lasted over forty years and took the Great Sage back and forth across the breadth of northern India.

Concerning his meditation after enlightenment and his decision to teach, in “Tactfulness” the Buddha himself says,

[I] again reflected thus:

‘Having come forth into the disturbed and evil world,

I, according to the buddhas’ behest,

Will also obediently proceed.’

Having finished pondering this matter,

I instantly went to Varanasi.

Here the Buddha is saying, “I came forth into this disturbed and evil world charged with the mission of saving it.” Buddhists always remember the Buddha’s resoluteness and great compassion for all living beings, which must be regarded not merely as expressions of the Buddha’s personal concern for us but as the real concerns of all humankind. Even if we feel that we are as yet very far from achieving the spiritual development of the Buddha, we must strive to accomplish the mission entrusted to us as ordinary people.

Undoubtedly, during the several weeks that he remained at Bodh-gaya in meditation and thought following his enlightenment, the Buddha devoted much time to organizing the teachings he would present in explaining the profound truth to which he had been enlightened. When he at last felt fully prepared, the Buddha departed on the teaching mission that would bring his message to others.

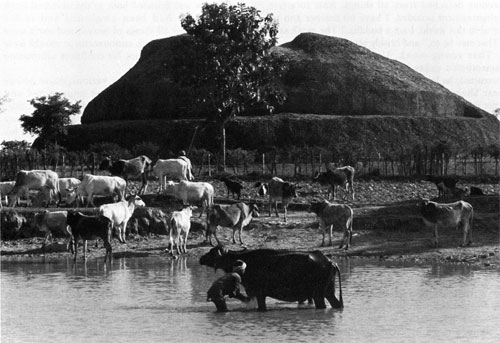

On beginning his mission Shakyamuni thought, “To whom should I first preach this Law? Who will be able to understand it?” His former teachers, Arada-Kalama and Udraka-Ramaputra, came to mind; but he learned that the two hermit-sages were already dead. He then remembered the five ascetics who had practiced austerities with him and later, becoming disillusioned, had left him. He was told that they were staying at Deer Park, near Varanasi, where many hermits gathered for ascetic practices. Alone, Shakyamuni made his way on foot to Varanasi, over two hundred kilometers to the west of Bodh-gaya.

Shortly after leaving Bodh-gaya, Shakyamuni encountered a young monk who addressed him, saying, “You look purified. Under whom have you studied in becoming a monk? To what kind of teaching have you devoted yourself?” Shakyamuni replied with quiet dignity, “I am all-wise, a victor over all things. I have extinguished all desires and become detached from all things. Able to attain enlightenment unaided, I have no teacher and no equal in this world. I am a buddha.” The monk said, “That may be so,” and briskly resumed his course.

That young monk, Upaka by name, is still remembered today because, by not asking to be instructed, he lost the opportunity to be the first to hear Shakyamuni’s message. Anyone who seeks after the Way must regard all people with whom he comes into contact as teachers and all places as proper places in which to learn the truth. For example, the Flower Garland Sutra contains the story of a monk called Sudhana-shreshthidaraka, who was able to learn a valuable lesson from a prostitute. Thus Upaka, who was immediately moved by the serene dignity of the Buddha, ought to have respectfully asked Shakyamuni to explain his enlightenment. Upaka was later to regret sorely that he had not done so, and he did eventually accept the teachings of the Buddha.

After walking many days across the hot plains of India, Shakyamuni finally reached Varanasi. He soon went to Deer Park, where the five ascetics who had accompanied him for six years were then staying.

Seeing a monk approaching, the five recognized him as the Gautama whom they had followed in his practice of austerities (Gautama was Shakyamuni’s family name). “That is Gautama, isn’t it? He is the fallen monk who failed in his ascetic practices. Let us refrain from paying our respects to him when he comes to us. However, we may give him some food…”

Though they spoke thus to one another, when they met Shakyamuni they were so effected by his dignity that they were incapable of remaining indifferent. Each rose unconsciously and received him reverently, making obeisance to him. They took his begging bowl, washed his feet and dried them, and prepared a seat of honor for him. They greeted him: “Our friend, Gautama!”

Shakyamuni then solemnly declared: “You must no longer address me as Gautama, nor yet as friend. I have already become a buddha. I will preach to you the eternal truth I have perceived. If you practice this according to my teaching, you will surely attain enlightenment and achieve your purpose in becoming monks.”

Anyone other than Shakyamuni making such a seemingly haughty statement, so similar to his declaration to Upaka, would have inevitably invited accusations of arrogance. It is not possible for the ordinary human mind to encompass Shakyamuni’s own comprehension of his buddhahood. His awareness was founded both in the universal truth to which he had been awakened and in his realization that all things of heaven and earth were his responsibility. His announcement would have been astounding without his confident affirmation “I am a buddha.”

Those who linger at the various stages before attaining buddhahood are yet unperfected and imprudent and therefore should always be modest. However, since Shakyamuni was a buddha, any reticence on his part would have denigrated his buddhahood. We must understand this point in order to appreciate that Shakyamuni was speaking forthrightly, not exhibiting overweening pride.

The five monks were inspired by Shakyamuni’s virtuous mien and paid him homage despite their initial reaction, but they did not consent immediately to listen to Shakyamuni’s teaching. In fact, at first they did not want to hear it. However, Shakyamuni, ardently desiring to enlighten them, addressed them three times, saying, “I will now preach the Law to you. Come and listen to me.” Three times they refused to heed him. Finally he said to them sternly, “Monks! Have I ever spoken untruthfully to you? Have I?” They recalled that he had always taught them with honesty, and they were moved by his compassionate wish to save all sentient beings from their sufferings. As they reflected on these things, a desire to hear Shakyamuni’s message gradually arose in them.

Shakyamuni had reached Deer Park in the afternoon, and he spent the hours from early evening onward alone in silent meditation. At midnight, when the sounds of the day had died away, a serene air stole upon the surroundings and Shakyamuni at last began to preach his epochal sermon.

“Monks! In this world there are two extremes—that of self-mortification and that of self-indulgence—that must be avoided. By avoiding these two extremes and following the Middle Path, I have attained the highest enlightenment.” Thus Shakyamuni began his first sermon.

He then preached the Four Noble Truths, teaching that man must recognize that life is filled with suffering (the Truth of Suffering), grasp the real cause of suffering (the Truth of Cause), and by daily religious practice (the Truth of the Path) extinguish all kinds of suffering (the Truth of Extinction). Shakyamuni went on to expound the Eightfold Path—right view, right thinking, right speech, right action, right living, right endeavor, right memory, and right meditation—as the Truth of the Path leading to the extinction of all suffering. First Ajnata-Kaundinya and then each of the other bhikshus, or monks, reached the first stage of enlightenment, becoming free of all illusions. Speaking of this first sermon Shakyamuni says, in Chapter Two of the Lotus Sutra,

The nirvana-nature of all existence,

Which is inexpressible,

I by [my] tactful ability

Preached to the five bhikshus.

This is called [the first] rolling of the Law-wheel,

Whereupon there was the news of nirvana

And also the separate names of Arhat,

Of Law, and of Sangha.

The expression “rolling of the Law-wheel” requires some explanation. In Indian mythology the ideal ruler, known as a wheel-rolling king, was supposed to govern by rolling a wheel and to rule not by armed might but by virtue. In Buddhist terms there are four such kings, each with a precious wheel of gold, silver, copper, or iron, in accordance with how large a portion of the world he rules. The king of the gold wheel unites and rules the entire world.

The Buddha’s Law is like the wheel of gold. When a great sage preaches this Law it is as if he had rolled the gold wheel: all come to respect and honor him and his rule, or teaching. Thus “to roll the Law-wheel,” or the “wheel of the Law,” means to teach the Buddha’s Law.

During the forty-five years between his first sermon and his death, Shakyamuni ceaselessly rolled the Law-wheel in the villages and countries of northern and central India, and that Law-wheel continued to roll even after his death. In one direction, it rolled through Central Asia into China and Korea and on to Japan; in another direction, it rolled throughout Southeast Asia.

Reprinted with permission from Shakyamuni Buddha: A Narrative Biography, by Nikkyo Niwano (Kosei: Tokyo, 1981), 46-59. (c) 1980 by Kosei Publishing Company.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.