RECOGNIZING the inherent Buddha-nature of rocks and clouds is not that hard—many acknowledge this in principle. Liberal thinkers admit most animals and plants and even microbes to the select company of sentient beings. Rocks and clouds are beginning to be accepted, too, as part of the “natural living world,” i.e., the world that existed before mankind brought civilization out of his brain and spread it across the landscape. But recognizing this prized quality of aliveness in technology, in human/machine interaction, and in abstract symbolic systems is something else again. Buddha-nature in nuclear bombs? In computer systems, in our urban networks, in the workings of pure mathematics? No one in the environmental world seems willing to go that far; only cyberpunks and techno-futurists have such thoughts, and they are generally dismissed as frivolous by us serious, “nature”-loving Deep Ecologists. We Buddhists, and Muirists, and Thoreauists.

Today’s Deep Ecology seems to regard technology as an evil force, something alien to the natural world, loosed by almost-divine mistake on this planet. These new energies are not regarded as legitimate expressions of sentience, universal life force, nor are they granted the respect that we accord to “natural processes”; rather they are seen as something wrong, something to be controlled and repressed. Deep Ecologists show the same fear and loathing toward today’s out-of-control technology as humans have had—until just recently—toward uncontrolled Nature, with her savage wastelands. Just as we waged war in the nineteenth century on wilderness, environmentalists today long to conquer technology, to subdue and control it.

Such a dualistic view of the world, neatly partitioned into good, pure nature and bad, aggressive technology, does not lead to a complete relationship with everything that is. It perpetuates the same kind of good guy/bad guy scenarios we have always indulged in, and leaves a bad taste, especially since the bad guys seem to be winning. Why not take Deep Ecology all the way to the heart of what is really wild on this planet: why not embrace as sacred Everything That Moves, just as we do in a wilderness system? Since everything that exists moves, we’d be done with all this picking and choosing, worry and strife. We’d have ready-made, flawless, sacred outlook.

The Deep Ecology Establishment

The ambivalence of deep ecologists toward technology is seen clearly in the recent book Gaia’s Hidden Life, by Shirley Nicholson and Brenda Rosen. Wonderful arguments are presented for the recognition of living beings in the natural world, even among rocks and stars, etc. But almost every one of the twenty-seven authors, from James Lovelock to Thomas Berry, rejects technology as an invalid, unnatural, even wicked, form of existence. Meanwhile, they idealize the vanishing dream of free, wild biological systems. They would restore them to their erstwhile splendor—as though evolution ever moved backward!

This point of view is called biocentrism, and is proudly opposed to anthropocentrism, our outmoded “humanist” outlook. But biocentrism seems little better. It is based on the assumption that evolution reached its pinnacle not with Man, but with Biology. But evolution isn’t like that. It never reaches a pinnacle. It never rests, and never turns back.

A contemplative biologist would not want to be “centric” about any stage of the evolutionary process. The earth is no longer seen as the “center” of the universe, humans are no longer thought of as the “center” of evolution, and there’s no reason biology should be, either. Evolution unfolds continually and mysteriously out of itself. It has no goal, claims no achievements, and is uninterested in any past or future states. Just this mysterious present moment unfolding, in which there is nothing to cling to, nothing to be “centric” about. To students of Buddhist dharma this may sound familiar. Many people have come to understand the working of mind, the theory, and also to some degree the practice of nonduality, nonclinging—but we still seem to hold primitive, “centric” beliefs about planetary evolution and local biologies.

The leading Deep Ecology thinkers all seem to have this biocentric attitude—Gary Snyder, Arne Naess, Bill Duvall, John Seed, Dolores LaChapelle, and so on. Many of them have good dharma teachers too, but in my opinion they don’t listen to them carefully enough. They talk about surrender to what is natural, and about following the Tao, but are not willing to stretch their arms wide open and let in Everything that Moves. They would like to exclude certain things: exploitative technology, warfare, social injustice, famine, urban landscape, television, the extinction of noncompetitive species, the collapse of planetary life support systems for higher species. . . .

You have to go to Walt Whitman and William Blake for a view in which all of life is honored impartially, devils and angels together on their own scary terms. Many Zen and Tibetan and American Indian teachers know this, Rumi says it over and over—contemplatives seem pretty clear on this understanding. It’s time for deep ecologists to get up to speed here. This naive, biocentric view exists because deep ecologists are not contemplative mystics. They became ecologists, specializing too early in a limited professional expertise on the “natural environment.” Serious ecologists must learn to let go of personal or social agendas, and embrace everything that arises. Only after this surrender can one go deep.

Such a Deep Ecology might not seem to be especially “environmental,” because it doesn’t cling to any version of reality; it continually surrenders to whatever situations occur. This viewpoint doesn’t directly advance the work of saving the planet or preserving local landscapes, but it could be helpful for environmentalists nonetheless. Because unless we enter into the heart of that Wildness where life itself is continually born, we remain outsiders in our own world, and outsiders never really know what’s going on. Outsiders can’t help sentient beings.

Negentropic Evolution

In a Nondual Ecology, all forms of life are honored equally. This includes everything that displays negentropic activity, i.e., the self-organizing, information-encoding, entrophy-defying activity of dissipative structures, as described by Ilya Pirogogine and others in the field of Complexity.

Negentropic processes defy, on a local level, the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which condemns all forms of existence to slow death by entropy, or disorganization. Instead of gradually losing their information structure, dissipating their energy, and running down into amorphous thermodynamic equilibrium, negentropic structures, all by themselves, increase their energy levels, internal complexity, and degree of self-organization. In the domain of the life sciences, this energetic self-organizing activity is as surprising in its way as perpetual motion would be, especially if the motion got stronger and stronger over time. Such things are considered impossible in classical physics on any large or long-term scale, but the life processes on earth have lasted four billion years so far, saturating the entire planet and overflowing the solar system. If we weren’t so used to this process by now we’d call it a miracle, and some still doubt it could be taking place on other planets.

I consider all such activity, spontaneously arisen on the pristine, untouched wilderness of this planet, to be the precious stuff of life itself, naturally free and primordially pure, whether we like it or not. Many of these entities or technobiotic processes are dangerous, but so are the natural forces in large biological wilderness areas. We have at last come to appreciate this element of danger in nature; perhaps we must learn to accept it as well in the world we live in today—in the world of cities, wars, famine zones, collapsing ecosystems, toxic pollution, and so on, including the extinction of species and even perhaps the disappearance of “higher” life forms on this planet, like ourselves. This kind of danger may be good for us, even healthy.

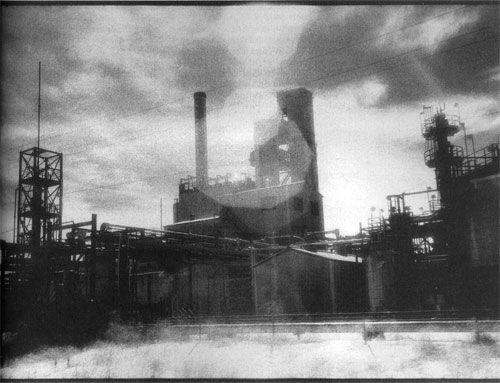

What are these wild new forms of life that have taken over the planet recently, these machines, the social and metabolic behavior systems of civilization, the new energy, information, and transportation networks that hold our planet in such a close and deadly embrace? Are they authentic biological entities, legitimate expressions of sentience, the result of the natural working of evolution on a pristine planetary wilderness?

The Evolution of Non-DNA Life-systems

The whole biological kingdom—all the animals, plants, microbes, etc.—is made up of “morphs,” or bodies, built according to the information codes contained in the DNA molecule. Until recently no information codes sufficiently complex to build bodies or shape behaviors existed on this planet outside of DNA. Nothing else could hold the complex data required to build a functioning object that could consume fuel, dissipate heat waste, maintain and repair itself, and copy, or replicate, its own precious life-giving information code. Not the clouds, not the air, not the sunshine or the heat in the earth, not water or mud, not the rocks, not even the silicates and crystals—in all the vast world of the four elements, i.e., the material universe, all was dead, inert, subject to entropy. Only DNA was negentropic.

So four billion years of DNA-driven evolution went peacefully by, age after age of dreamy biologies. Finally one of the morphs, or body types (humans), developed an incomprehensibly large brain, capable itself of independently storing and manipulating information structures complex enough to generate morphs or bodies of their own. At last, a new copying system! Human brains set loose the powerful symbolic systems of language, alphabets, mathematics, engineering, arts and crafts, religions, belief systems, social customs, and so on, and the world of technology and culture was born.

With the tremendous symbolic activity that our brains allowed, information codes had suddenly jumped out of their ancient amino acid cradle and began to pursue “their” own evolutionary destiny. A torrent of new morphologies and behaviors were loosed on our innocent, unsuspecting planet. New tools, new hunting, new farming and herding behaviors, new buildings, new forms of social organization—collectively referred to as technology, culture, or civilization. In a blinding flash, as seen from the evolutionary time frame, the planet has been transformed. A wildly unpredictable, radically new form of evolution is unfolding here. Information codes are free to form morphs and replicate in any way they wish or are able.

So who are we now? Are we still pure biological creatures? Is it even possible to conceive of technology, machines and information systems, etc., as a separate class of existence from humans? I think not. We have become technobionts, symbiotic members of this new life-form that has taken over the planet. Our “human” nature has merged with the new morphologies to become technobiotic nature. Humans are not in control of this process; we are merely a part of it. It is happening to us, and in spite of us, as well as because of us. In this case we are the host organism, the medium in which technobiotic life forces are finding their fertile soil. We humans, with our obsolete bodies, easily exploitable emotional drives, and fabulous brains, are the primeval soup our symbiotic partners have come to live in.

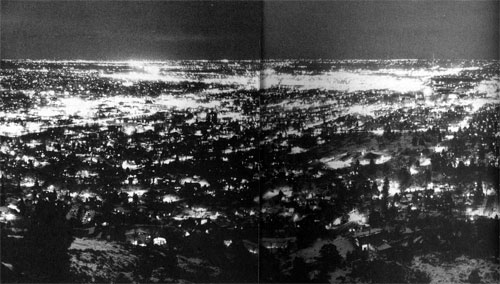

Like it or not, biological evolution is no longer the main focus of life on this planet. Biological evolution has become a subplot, relegated in its wild forms to out-of-the-way comers, to empty lots, roadsides, to cracks in the sidewalks of civilization. It’s been built over, on top of, subsumed, in the best evolutionary style, by the technobiota. We cannot stop this process; we cannot even guide or shape it very well. We are locked into an unfolding dynamic that has its own evolutionary momentum. We and it are out of control together in a stupendous Becoming that stands proudly beside any evolutionary step ever seen before in this part of our galaxy.

So in any discussion of ecology, whenever one refers to rocks, clouds, rivers and mountains, microbes, animals and plants, one should include kitchen tables, cars and computers, stuffed animals, and nuclear reactors, as well as abstract symbolic systems such as mathematics and music, and belief or behavioral morphologies, including social systems, religions, culture, etc. These are all valid forms of life, if we and rocks and clouds are.

Sentient Being Is Inconceivable

Sentient beings may be precious, but they are also unthinkably numerous, inexhaustible, existing abundantly in the past, present, and future in every possible kind of world. Their existence is beyond conception and takes place in a sacred manner: it needs no protection, and is vulnerable to no threat. It isvajra, indestructible. This magical quality is its supreme protection and must be grasped properly before we can have a good relationship with the world of beings we live among.

Sentient beings are inconceivable, so only inconceivable methods can help them. Ordinary methods are of no use here—they do not need to be saved in a museum on a shelf or in a zoo, in a park or wildlife refuge or biosphere, in a hospital, school, or jail, in low-cost housing or refugee camps, in books, photographs, or nature videos. Living in all times indiscriminately, they are not separate from the rest of the cosmos. They cannot be saved or even conceived of as separate parts. The entire cosmos is saved, or lost, as one integral principle. Consider the Diamond Sutra on this:

The Integral Principle

Subhuti, if a good man or a good woman ground an infinite number of galaxies of worlds to dust, would the resulting minute particles be many?

Subhuti replied: Many indeed, World Honored One! Wherefore? Because if such were really minute particles, Buddha would not have spoken of them as minute particles. For as to this, Buddha has declared that they are not really such. “Minute particles” is just the name given to them. Also, World Honored One, when the Tathagata speaks of galaxies of worlds these are not worlds; for if reality could be predicated of a world it would be a self-existent cosmos and the Tathagata teaches that there is really no such thing. “Cosmos” (or, “life bearing planet”) is merely a figure of speech.

Then Buddha said: Subhuti, words cannot explain the real nature of a cosmos (or “living planet”). Only common people fettered with desire make use of this arbitrary method.

(Chapter XXX)

This is not an easy emptiness “exit” from the tragic plight of our earth, a cheap shortcut to a “higher view” to avoid grieving for what is lost, to erase or escape from the sorrow and joy of the vast birthing and dying that is taking place on our planet today. The sorrow is true and should be tasted fully. But it helps to shift one’s grip a bit, to avoid getting clutched up on a fixed version of reality—Mother Gaia isn’t like that. She didn’t get where she is today by clinging to fixed versions. She doesn’t favor any of her innumerable children over any other.

Saving Sentient Being

The saving of sentient beings is perhaps the most confusing issue in contemplative work. All are in agreement, this must be done, but who are the sentient beings, how are they to be saved, and on what scale? What about those who are out of reach, or worse yet, who dwell in past and future times?

I’ve sometimes thought the greatest single clarification that could be brought to this subject might be to drop the s from “beings.” The project suddenly becomes the vaster and simpler one of saving Sentient Being. Immediately we stop worrying how to handle the crowd of particular individual beings, more or less accessible to today’s saving methods—each of whom has passed a qualifying exam for sentience (no rocks, dust clouds, or empty space, no computers, shovels, old car tires, etc.), has demonstrated clear and present need of saving, is in fact a separate, individual ego entity, has not been previously saved by others (it’s getting hard to find unsaved beings anymore), and so on.

Simply drop the bothersome s, and Sentient Being itself looms up. vast, inconceivable, glowing and humming, in all ages and all spaces—indestructible, beyond confusing particulars. This vast Presence of aliveness, of sentient Is-ness, filling the time-space cosmos from beginning to end, dwarfs all bodhisattvas, all saints, revolutionaries, and liberal reformists—it silences the poets, and overflows even the hearts of mothers. It is inexhaustible, self-sufficient, needing nothing, wanting nothing. Suffering is as natural and organic a process to it as breathing. The tides of life and death are its diastolic rhythm.

Who would dare try to “save” this vast Presence? Save it from what? Who would wish to “alleviate” the suffering/breathing, living/dying of Sentient Being? Any who approach this Being with a “saving mind” would have to have the greatest humility, the greatest respect, the greatest hesitation, and the greatest boldness. The lack of an s might even cause some investigators to question the need for the qualifier “sentient” . . . Are there any boundaries to sentience? Can the universe be divided up into sentient and non-sentient regions or beings? Is the whole universe not completely sentient, one being? Try saving That by ordinary methods.

As for the innumerable creatures on our planet who are undoubtedly suffering and in need of assistance, including very much and most especially our own “personal” selves, our ability to see and share the true nature of these beings is more the issue than our good health and large numbers. This saving may have more to do with being with them than with preventing their extinction or raising their minimum income level or wiping a bit of pollution off their brow. Sentient beings can for the most part take care of themselves, just as we like to think we can. Considering them in this way is a mark of respect; it honors them. Compassion is a curious word: “with-passion.” Passion is pathio (Latin), from pathos (Greek), and actually means “suffering.” So suffering-with. First comes “knowing,” then at the same time comes “suffering-with.” This complementary dual emphasis is the winsome way of the Buddhas with sentient beings. Maybe it should be the way of deep ecologists with ecosystems, too.

This deep frame of reference may seem chilling to some, but it is not. On the contrary, it warms the heart and lightens the step, and it should help to save the earth and advance the agenda of conservation biology, too, along with any other worthy projects. The buddhas and patriarchs may play rough, but this roughness is good for us. There’s no reason in the world that environmentalists shouldn’t be able to hold a deep view and still be energetic and effective, good people to have around when things are tough. We aren’t babies. We can look at Reality along with the rest of sentient beings. Biology may not be the only thing evolution has planned for this planet. Doesn’t seem to be, does it? We do not need to tell ourselves children’s stories about how unique and precious we are, to make ourselves go out and help the world. In fact, we are precious and worthless at the same time. We are neither precious nor worthless. It’s not like that.

This is non-dual ecology.

Dynamic Evolution, not Fixed Ecosystems

Deep Ecology is good, but not always useful in everyday life. We need a working ecology, something tough and flexible, something that can be used to save the world. This practical ecology might come in two parts: view and practice.

The View. Reality is as perfect today as it has ever been. The world in this moment, along with one’s mind in this same moment, is the Great Perfection spoken of in the teachings. It must be enjoyed just as it is—pollution, warfare, famine, poverty, confusion, materialistic greed, and all—no matter how unlikely, unhappy, or sorry a specimen of world or mind it may seem to be. Ecosystems, like minds, are always in perfect balance, even when they’re neurotic, ill, confused, or going extinct, miserably and unnecessarily.

The Practice. A dynamic ecology has got to work in a world that is changing from one moment to the next. Ecology cannot be based on an attempt to preserve ecosystems at some particular stage of their evolution, no matter how beautiful that stage may have been. This is like trying to prevent children from growing up, or old people from dying. It is a form of materialism to be overly attached to a special set of God’s works, and it is doomed to failure in any case.

We will never achieve our dream of attractive, healthy ecosystems—they will always be collapsing around our ears. This is what ecosystems do! They have a natural lifespan, which in addition to being short is frequently terminated “unnecessarily” early by accident or misfortune. Just like our own lives. Wanting to freeze ecosystems at a certain stage of their existence is like our other foolish dream of always being young, attractive, and healthy.

Everything That Moves

The only ease lies with the process of evolution itself. Sound ecology must be based on respect for evolution’s creative/destructive working process, not on a childish clinging to pretty toys it may have made. Then we can live in this world, help it out, and lean into its mysterious unfolding.

To combine this challenging view with the challenging practice, one simply regards everything that moves as a form of sacred activity. The mad materialist technobiotic frenzy gripping the planet is nothing other than this. There is only One Thing happening, not some things that are good and others that are bad. This Thing includes fragrant ecosystems, fresh and unsullied in wilderness areas on spring mornings, and it includes urban industrial megagrid, ghettos and famine zones, materialistic greed, the extinction of wild animal species, and the slavery and torture of “domesticated” ones. Life and death. Even television.

Everything we love will die, and everything we hate will live, and vice versa, and we will never be rid of such problems. Death is sacred activity. What is happening on this planet today is the sacred activity of life and death, which we sometimes call evolution—Edward Abbey, Earth First!, and the Sierra Club notwithstanding. It is perfect as it stands, flawless, without blemish. But, as Suzuki Roshi said, there is always room for improvement too.

So it’s proper to fight and struggle with the situation, to take care of each other, and try to save a few sentient beings. We must do this, and we do, just as we struggle to improve the “climate,” “landscape,” and evolutionary process in our own minds and hearts. The thing to be careful about is not to reject what is cruel, dangerous, and poisonous, even the heartless machines, the computers and TVs, cars and highways, nuclear bombs, animal and plant torture, and money.

These are our sacred enemies. They might even be our sacred friends; one never knows for sure. We should not try to know for sure. It’s none of our business. To try to distinguish friend and enemy on this level is disrespectful. To the enemy, one offers a deep bow, as deep and as filled with respect as one offers to one’s friends and teachers. This bow is offered to everything without reservation. It is a form of protection. It saves us from attachment and illusion, and in the end, from despair.

Only One Nature

We can choose to regard all of existence as “alive,” or we can regard it as “not alive”; we can regard it as “both alive and not alive,” or as “neither alive nor not alive.” These are all valid ontological constructions. What we cannot do is divide existence into two classes, and call one of them alive and the other one not. One a “natural,” kind, pure, and nice biological nature, and the other a raw, unnatural, alien, bad, ugly, industrial, nuclear, polluting, materialist, urban nature. There’s just one nature around here.

As environmentalists, we must learn this way too. Bowing to what is, working hard and politely to improve it on a local level at the same time. Not trying to change the larger design. but simply contributing some tidiness and sanity to our immediate surroundings. Keeping a nice camp in this great howling universal wilderness, a reasonably safe and comfortable place where the gods are honored, the children are cared for, and good fun is had.

Outside such a camp there is Great Wildness. Sacred beings roam out there on the street, enjoying dangerous degrees of sacred freedom. The gods are in charge out there. What they choose to do and to leave undone is their business, not ours. No one tries to control what goes down on the street, no one but gangs, drug lords, and cops. You don’t want to be like that. You want to be a bodhisattva of compassion and awakeness, with sympathy for all forms of life. You want to tiptoe through the street in a state of reverence and awe, armed if necessary and able to defend yourself, as in any wilderness area—but always respectful of whatever you meet. Whatever. The street, regional ecosystem, or planet, should be considered a wilderness area, free to define itself no matter what happens. This is basic wilderness ethic, and is the first and greatest rule of all Deep Ecology.

Reality does not need or want to be changed. It has gone to great trouble to establish itself as it is, and it is perfect. This very world of today, as it appears before us in all its glory and horror, is the sacred landscape we live in. What is. Our role is not to arrogantly critique this Great Perfection, picking and choosing in it according to the conventional wisdom of the day; our job is simply to join in with it. And there’s no need to have a poverty mentality about the life in this world. It is not now and has never been in any danger. No matter what happens on this planet, there will always be plenty of good life-filled worlds for us to join in with.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.