Standing before the two hundred people assembled at the defunct elementary school of Clatskanie, Oregon (pop. 1,528), one woman didn’t mince words about her opinions. “The aura of Satan is taking a foothold. We do not want Buddhism in here.”

Many of the others shared her views. Soon the suspicions of some residents of this small town ninety minutes from Portland would bring it into the public eye, forcing it to wrestle with difficult issues of religion, freedom, and community in an age of fear and uncertainty.

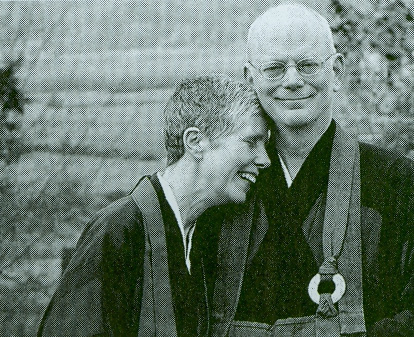

When Hogen and Jan Chozen Bays, husband and wife co-teachers of the Zen Community of Oregon, began their quest for a monastery, they didn’t expect to stir such passions. ZCO was founded in the mid-1970s, and Hogen and Chozen arrived in 1984, sent from the Zen Center of Los Angeles to lead the growing sangha. They had always yearned to establish a monastery where full-time residential students could take the dramatic plunge into the deep end of Zen training, but nothing permanent materialized, and the group ended up sitting in campgrounds around the state. So in 2001, when they discovered that Clatskanie’s Quincy Mayger Elementary School was on the market, they jumped at the chance to finally bring about their vision for Buddhism in America.

It wasn’t long, however, before the problems began. By early 2002, rumors of a cult had spread around Clatskanie, so ZCO decided to hold an open town meeting at the school to address local concerns and answer questions. Many of the people who showed up were simply curious about all the fuss, but the largest single contingent had come from a local fundamentalist church opposed to what they considered a threat to their way of life. Accusations flew about Buddhists coming to target the town’s children, leading them onto a path of darkness.

The Zen group would have to do some serious work to overcome the suspicions they encountered. Hogen Bays took the lead, describing his approach this way: “Our basic philosophy is to be wide open—that’s the best way to make the community comfortable, and for us to get to know them.” Day after day, he made the rounds, meeting with the Kiwanis, the postmaster, the mayor, with local business leaders, with ministers, with people on the street. Everywhere he went, he listened to people’s concerns, did his best to explain what would and would not take place at the monastery, and learned about the community he and Chozen would be moving to.

As months passed, the process of leasing the school site dragged on, with opponents turning up at school district board meetings to voice their objections, lodging appeals whenever decisions in the ZCO’s favor were passed. The media caught wind of the conflict, and soon articles, editorials, and letters to the editor began appearing in publications around the state. People began to argue about what it meant to be an Oregonian, an American, a neighbor. Ultimately, it was this public debate that seemed to make the difference.

“That was the best thing that happened to us,” Hogen said about the media’s interest. “People came out of the woodwork from all over to support us. This incident really gave a voice to people who have a broad, generous heart, Christians as well as non-Christians.” Concerned that their town was being portrayed as a bastion of intolerance, more and more Clatskanians came forward to encourage the Zen group and let their leaders know that there was room for all in their community. Finally, at the end of May, the last appeal was dismissed and the way was cleared for the founding of Great Vow Monastery.

Hogen and Chozen Bays now live at the former school, along with a dozen other full-time residents. The school’s former library has become the zendo, and students have the privilege of practicing at perhaps the only Zen center in the West with a cafeteria and gymnasium. Requests for admittance have come in from all over—Oregon, Alaska, New York, even as far away as Japan. The initial conflict with the surrounding community and the eventual triumph of the ZCO helped confirm the Zen group’s open, patient approach to problems, and highlighted the need to stay engaged with the wider community, both supporters and detractors. “The monastery is the center of a community—that’s been our model,” said Hogen. The result has been many friends made, who smile when they see Hogen’s shaven head passing by on the street, and many Clatskanians have come to the monastery to take part in activities. Though they are currently leasing the property, the Zen Community of Oregon hopes to buy the school and its twenty acres for $1.02 million in the next couple of years.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.