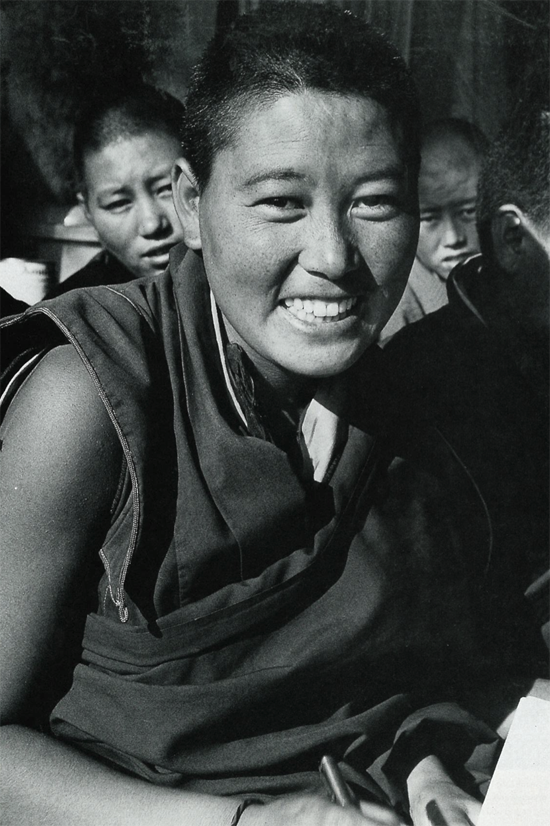

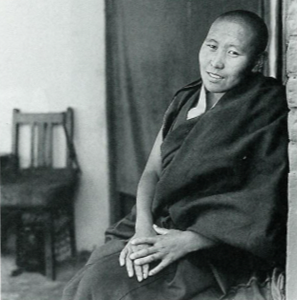

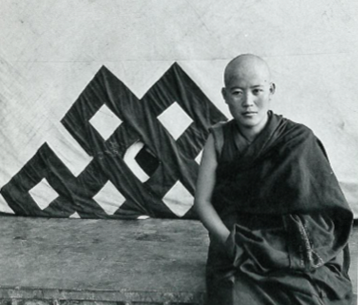

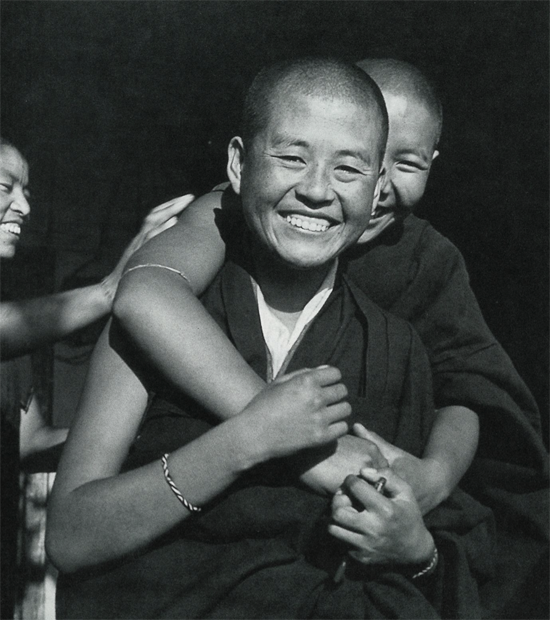

Prior to their life in exile, many of the nuns in Tibet had demonstrated against Chinese rule. As a result, they were threatened, imprisoned, and tortured. Nuns who remained in Tibet held demonstrations in the late eighties and early nineties in Lhasa. Circumambulating the Jokhang Temple in Barkhor Square, nuns would shout, “Free Tibet!” “Chinese quit Tibet!” and “Long live the Dalai Lama!” During one such protest in 1991, Chinese police arrived, tied the nuns’ arms behind their backs, hit their faces, and kicked them to the ground. The nuns were taken to Gurtsa Prison to be interrogated. The police demanded to know why the nuns were protesting and beat them with sticks and electric batons. During imprisonment, which for some was three months and for others five years, they were made to kneel on sharp stones for hours, beaten repeatedly by groups of police, and chased by dogs. Due to these beatings, some nuns have permanent internal injuries, hearing loss, or mental impairment. Yet their faith in the Tibetan cause is so strong they are willing to sacrifice their lives.

Many were nuns from Shugsep Nunnery near Lhasa. The nunnery was established by Shugsep Jetsunma in the late nineteenth century and was completely destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. Following the Chinese occupation of Tibet, the nuns were forced to leave. Although Shugsep Nunnery was partially rebuilt in the 1980s, continued restrictions and harassment by Chinese authorities prompted the flight of a new generation of Shugsep nuns to India in the early 1990s. For those who fled, the trek through the snow-covered Himalayas took about seventeen days, a strenuous journey that threatened frostbite and starvation.

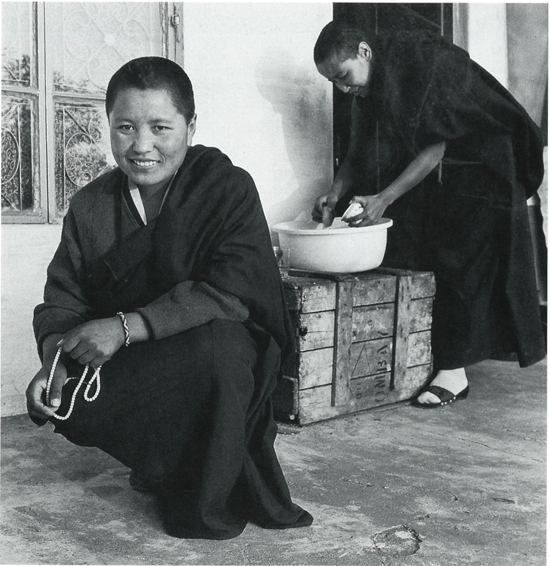

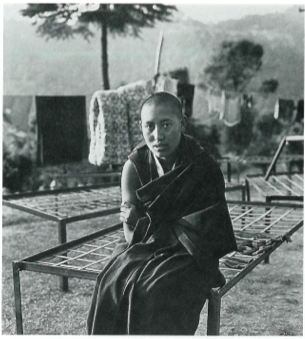

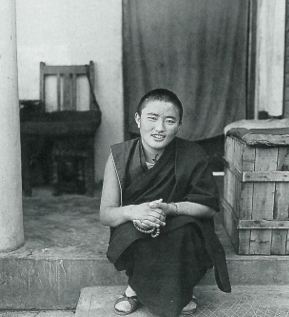

There are now approximately fifty Shugsep nuns living in Gambir Ganj on the outskirts of Dharamsala, home of the Tibetan government-in-exile. Here, a nine-year program is offered in Buddhist philosophy and practice, Tibetan culture and language, and English. The Tibetan Nuns Project (TNP), established by the Dalai Lama in 1987, hopes to purchase land and to establish a nunnery-in-exile in India for these Shugsep nuns, which will allow unrestricted religious practice and observance of their cultural traditions.

Another forty nuns arrived in India following a pilgrimage from their home in Litang. Starting in 1988, they walked the length of Tibet doing full prostrations, which involves repeatedly taking three steps, then lying prone—stretched out with face and body to the ground. Their goal was to reach Jokhang Temple in Lhasa. Wearing Chinese canvas shoes, they would stop at night and ask who had the needle. There were two needles for the group, and the nuns would take threads from their chubas (robes) with which to repair their shoes. Reaching the temple two years later, the nuns were turned away by suspicious Chinese police. Upon being interrogated, the women feared they might be arrested, so they fled. Joined by another twenty-six nuns, the group left Tibet to attend the Kalachakra teachings and initiation given by His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Sarnath, India, during December 1990. From there the nuns made their way to Dharamsala, arriving in early 1991.

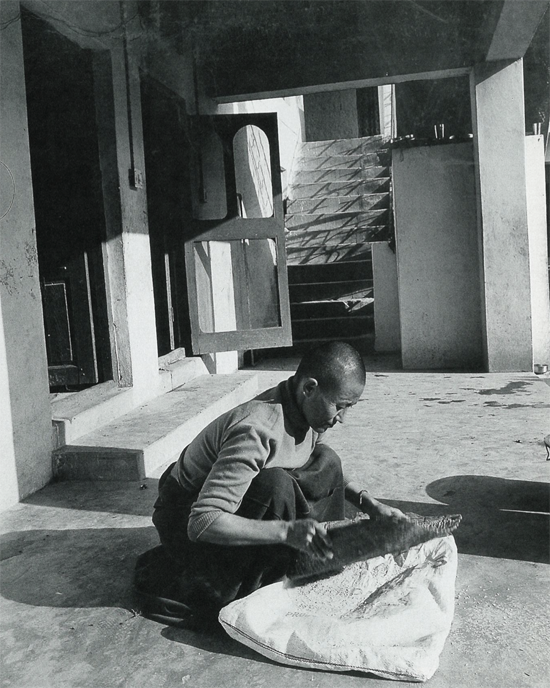

These women, aged twelve to thirty, were temporarily housed in two buildings in Gambir Ganj on the hillside below McLeod Ganj, Dharamsala. They had no beds and few blankets. The kitchen was set up outdoors, and they shared one cold-water spigot among them. Under the sponsorship of TNP and the Tibetan Women’s Association (TWA), conditions have been steadily improving. These nuns have now been relocated to the Dolma Ling Nunnery and Institute for Higher Learning, established by TNP in the area of the Kangra Valley just below Dharamsala. It offers a thirteen-year, nonsectarian curriculum combining traditional and modern programs. Nuns, if they wish, can receive the degree of Geshe (comparable to a doctorate), previously only available to monks.

Tilokpur Nunnery, located about ninety minutes from Dharamsala, is home to over sixty nuns in the Kagyu tradition. These nuns devote a minimum of two hours a day to meditation, and their practice frequently leads to a three-year retreat. Tilokpur has implemented an academic program as well. Both Tibetan language and English are taught. In general, they struggle with the difficulties of balancing the duties necessary to establishing the nunnery with the requirements of study and meditation. TNP has helped to improve medical care and nutrition as well as providing teachers and sponsors to help support the nuns.

“When I was fifteen, I joined a nunnery. I find that the circle of life is full of problems which have no ends, and problems women face when giving birth to children. I don’t want to go through all this. So the circle of life is quite worthless, and I decided to practice religion and become a nun. This will help both in this life as well as in the next life.”

—A twenty-three-year-old Shugsep nun

“If we do something in Tibet, or say something in Tibet, then the Chinese collect these political prisoners like collecting stones or firewood. They will treat us like inanimate things. There are many prisoners in Tibet . . . who are struggling under the Chinese day and night . . . their life is horrible and intolerable under the Chinese rule. I feel that if my experience (in Tibet and particularly in prison) is of some use for the people who are left in Tibet, then I would be most grateful to people who listen to my story, which is an example of the Tibetan people.”

—Ani Gyaltsen Chotso

“I was seventeen . . . . and did [fieldwork on the farm] for five years [after graduating from school]. After seeing worldly ways and suffering, I wasn’t happy with such a life. So I thought that I could become a very good nun; I can obtain a Buddhahood at any time, which is not only beneficial for oneself, but for all sentient beings. If I can’t attain Buddhahood, I can have a very good life without harming others. My father was also a very religious-minded person. He used to tell me about leading a very religious life. So these two things moved me to become a nun.”

—Ani Ngawang Palmo

“I didn’t have anger, but I felt scared when [the Chinese] were beating me. I feel pity for them because they are innocent and ignorant. . . . they don’t follow any religion. They don’t believe in life after death. They don’t have any feelings toward fellow human beings. So they don’t give any value for kindness and compassion in their life. In Buddhism, we try to accumulate as much merit as possible by being kind and compassionate in one’s life so that we will have good human life in the next life. But they don’t have such beliefs.”

—Ani Ngawang Palmo

“When you are the eyewitness to actual torturing and killing of your own people, you don’t have time to think about your life and your family. This is what is happening in Tibet. . . . [Tibetans] sacrifice for the country. They sacrifice their lives for freedom and peace in Tibet. When you see your own people being tortured or killed and see the living conditions in Tibet, you can’t sleep and your mind becomes restless. . . .Your feeling to your people will not allow you to sit around idle.”

—Rinzin Choenyi

“I went to Lhasa and stayed two months with relatives there. . . . I heard a speech by His Holiness the Dalai Lama on atape recorder. . . . I learned that the Chinese were telling the world that the situation [in Tibet] has improved a lot, but His Holiness mentioned that there are still a lot of demonstrations . . . . His Holiness said that these demonstrations show that Tibetan people are not happy and free under the Chinese because people don’t demonstrate and have an organized freedom movement when they are free and happy. So this speech of His Holiness gave me the courage and the inspiration [to take part in demonstrations]. . . . I realized there is no freedom in Tibet. . . . I felt that what His Holinesss said is real and trustworthy. . . . I got a sense of nationalism and patriotism. [I gained] the courage [to believe] that if I can’t practice my religion, but if I can do something for my country, I will be glad and happy myself. So I joined other . . . nuns and participated in the demonstration.”

—Shugsep nun

“If anyone from the family is politically active, like taking part in the demonstrations, then the Chinese won’t give you a job even if you have a good certificate and are qualified to do higher office work. In my family, they didn’t give a job to my brother even though he was qualified. My friend’s younger sister was not admitted to school. All this happened because my friend, Kalsang Palmo, her mother, and I were politically active. This is an example of what happens with Tibetans in Tibet.”

—Rinzin Choenyi

“I have not seen personally, but I heard from my fellow Tibetans that when any of the high-ranking Chinese officials need their organ (lung, liver, etc.) to be replaced, they exchange it with the prisoners. They bring a healthy prisoner and they tell the prisoner, ‘You need to be operated on to cure your disease.’ After transplanting the weak organ to the prisoner, he will be released. [The Chinese] say, ‘If you are cured, you are fortunate; if you die, we are not to be blamed.’ There are many cases like that. In this way, they are killing many of our people. I heard of two people who died due to organ exchange. They died two months after they were released.”

—Rinzin Choenyi

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.