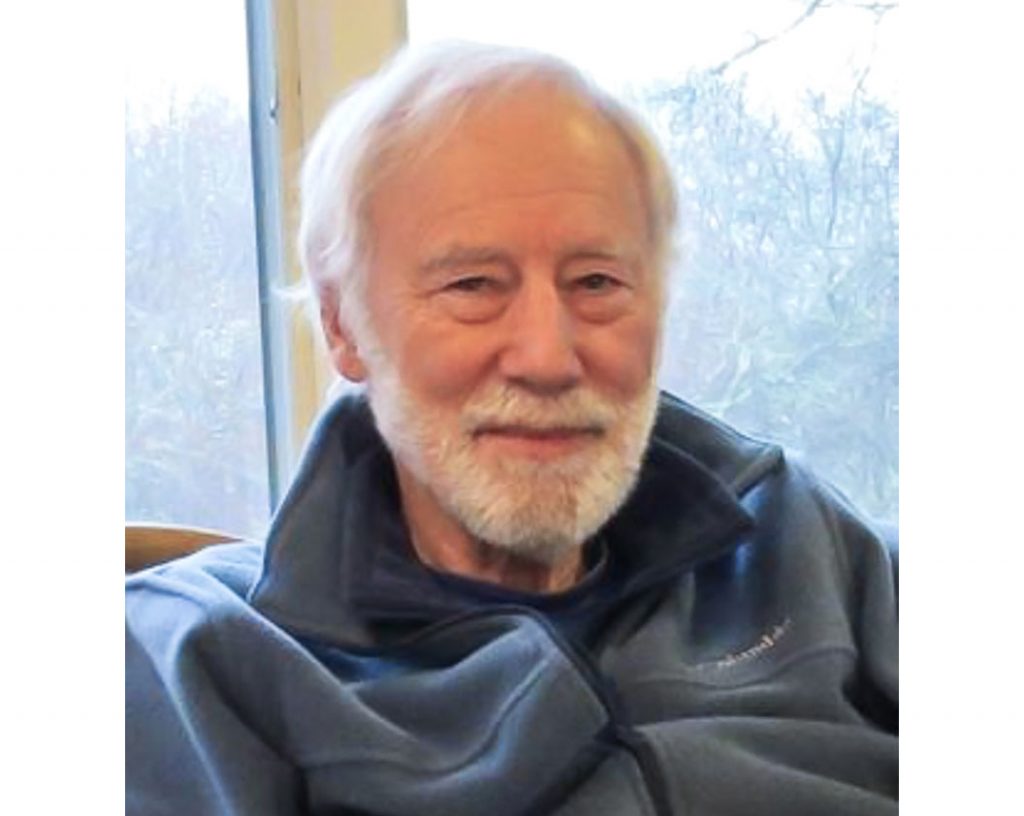

Clinical psychologist Jack Engler, PhD, widely acknowledged for his seminal work in linking Buddhist practice and Western psychology, died on March 12 in Framingham, Massachusetts. He was 83.

Armed with a PhD in clinical psychology from the University of Chicago and intense study with the Theravada Buddhist masters Anagarika Munindra and Dipa Ma, Engler had a long and storied career as a psychotherapist in private practice and an instructor at Harvard Medical School, as well as a Vipassana practitioner and occasional meditation teacher with strong ties to the Insight Meditation Society (IMS) and the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies, both in Barre, Massachusetts. In bridging the worlds of Western psychodynamic thinking and Buddhist practice, Engler will forever be remembered for his pithy summation of the development of the self and its relinquishment: “You have to be somebody before you can be nobody.”

No mere throwaway line, it emerged from his clinical work as a therapist and his experience teaching Buddhist psychology and Vipassana meditation. He first included that observation on self and non-self in an article published in The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology in 1984. After the article was reprinted two years later in Transformations of Consciousness: Conventional and Contemplative Perspectives on Development, a book Engler co-authored with Ken Wilber and Daniel P. Brown, the “epithet,” as he later called it, became a trope. His thesis on what he saw as “two great arcs of human development”—one leading to the individuated self, the other to a contemplative or transpersonal stage beyond it—garnered “a fair amount of criticism and notoriety from friends and colleagues for its developmental position,” he later acknowledged. His response to his critics and an effort to clarify his meaning was “Being Somebody and Being Nobody: A Re-examination of the Understanding of Self in Psychoanalysis and Buddhism,” a chapter in Psychoanalysis and Buddhism, edited by Jeffrey D. Safran and published in 2003.

Born June 19, 1939 in Boston, Engler was raised Catholic in Tenafly, New Jersey. His lifelong spiritual quest began in his undergraduate years at the University of Notre Dame, when he and fellow students spent Christmas vacations at Thomas Merton’s Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky. “The mystique grew on me—the shield of being in the monastery,” Engler later said in an interview for a documentary about IMS. “By the time I graduated in 1972, I was certain I wanted to become a monk.”

He spent the summer after graduation visiting monasteries in Europe to decide what order to join. After meeting Dom John Eudes, then Merton’s director of vocation, in Belgium, he chose the Trappists: “because,” he said, “of my perfectionist, gotta do the hardest, most challenging, most rigorous thing. If I didn’t do that, I would never know if I was capable of what I thought I was capable of.”

Despite his determination, his time as a Trappist monk was short. When Merton told him “You don’t belong here,” “it was probably the worst moment in my life,” Engler recalled. Merton steered him to the Oratory, an order in Pittsburgh founded by “a remarkable Christian saint.” Sent to Europe for theological study, Engler did a novitiate year in England and then spent four and a half “miserable” years in Germany. After finishing his degree at Oxford, he returned to the US where he taught at several universities.

Teaching psychology and Buddhism at the University of California, Santa Cruz, was a turning point. “I didn’t know anything about Buddhism,” Engler said. But this first brush with the dharma opened his mind, and he enrolled in the University of Chicago for a PhD in clinical psychology. He was searching for a thesis topic when another life-changing event occurred. One night in South Chicago, his car suddenly swerved off the street, and he found himself in the parking lot of the Vivekananda bookstore. He knew nothing about Vivekananda but bought one of the few titles in the store in English—The Heart of Buddhist Meditation by the German-born Theravada scholar-monk Nyanaponika Thera. After reading it that night, he told his then-fiancée, “This is it! This is what I’ve been looking for, for twenty years!” She had just returned from a junior year in India and persuaded him to spend a year there.

Awarded a Fulbright to study in India, Engler stopped first at Naropa in Boulder, Colorado, where he met Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfield, and Sharon Salzberg, who had just founded IMS. Joseph encouraged Engler to take their first three-month course. Joseph, Jack, and Sharon talked so much about their Vipassana teachers, Munindra and Dipa Ma, that Engler arranged to study with Munindra in India. After an arduous journey to Bodh Gaya, he finally met Munindra. “I’ve come a long way,” Engler told him, “and I’m completely, one-hundred percent in on this practice. Tell me what to do.” Munindra’s response: “How are your bowel movements?” His father was an ayurvedic doctor, and Munindra was knowledgeable about such matters. Still, “the first three or four weeks that’s all we talked about,” Engler recalled.

He found in Munindra a warm and loving teacher—very accepting, very gentle, and yet sharp. “I did not want someone who was as uptight and strict and punitive with himself as I was,” Engler said. One day as they were walking together, Engler begged, “Tell me about the dharma, please. I’ve been waiting.” “The dharma?” Munindra said. “You want to know about the dharma? The dharma means living the life fully.”

Engler’s field work for his PhD—studying the effects of meditation on practitioners—involved administering standard projective psychological tests like the Rorschach. Munindra and Dipa Ma agreed to be subjects. But as psychiatrist and author Mark Epstein recalled, “They just used [the tests] as teaching opportunities, turning the Rorschach into a description of the clinging self and its evolution through the dharma. They couldn’t stop themselves.”

Jack Kornfield related an exchange between Engler and Dipa Ma in which he told her that “getting rid of” greed, anger, and ignorance sounded “very grey.” “Where’s the juice?” Engler asked. “Oh, you don’t understand!” Dipa Ma said, laughing. “There is so much sameness in ordinary life. We’re always experiencing everything through the same set of lenses.” Without greed, anger, and delusion, however, “every moment is new. Life was dull before. Now, every day, every moment is full of taste and zeal.” (Excerpts from more of Engler’s conversations with Dipa Ma appeared in the Spring 2004 issue of Tricycle.)

After he returned to the US, Engler was invited to become a board member at IMS. He remained active there and at the Barre Center for many years. He was particularly supportive of the structure at IMS, which unlike many meditation centers, is collaborative, with the teachers on an equal footing and no guru at the top of a hierarchy. “That gave the institution an integrity in facing issues that would come up in the future,” Engler said.

In Boston, Engler opened a private practice that he maintained for many years, and he served as a supervising psychologist and instructor at the Harvard Medical School. Well known for his approach to depth psychology that drew on both Western psychoanalytic and Buddhist concepts, he published papers in journals, contributed chapters to books, and co-authored The Consumer’s Guide to Psychotherapy with Daniel Goleman. In 1989 he was invited to sit on a panel on “Transformations of Consciousness” with His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

“What made Jack special,” Mark Epstein said, “was that he was very sophisticated in Western psychodynamic thinking, not superficial at all. Very thoughtful but also deeply experientially involved in Buddhism. He was really wrestling with the questions that come up.”

Engler’s results were often surprising. In his study of the effects of Vipassana meditation on beginners, average meditators, and advanced practitioners, he found that even in the advanced meditators, practice led to no diminution of inner conflict. The difference was that the advanced meditators were more willing to acknowledge it. “To have that documented was very important,” Epstein said.

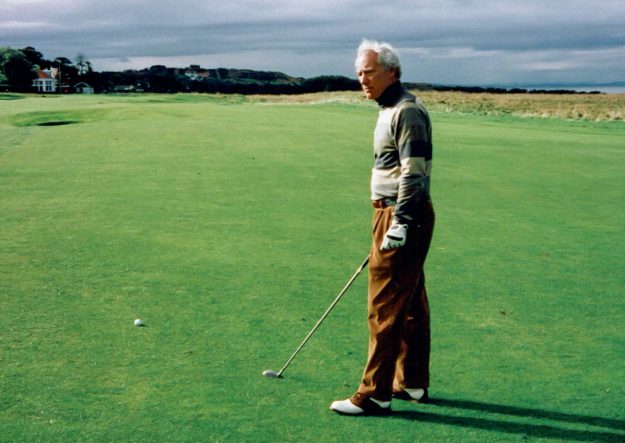

An accomplished sailor and passionate golfer, Engler is also remembered for his sense of humor and gift for storytelling. He was “funny in an inspiring sense,” said Ed Hauben, a close friend and dharma brother for forty years. They served on the IMS board together, and Hauben recalled a visit to IMS from Dipa Ma in which she told board members their service was fortuitous and would assure them a place in the heavenly realms. “With his bodhisattva nature, I’m sure Jack’s there,” Hauben said, “taking care of everyone.”

Engler is survived by his wife, Renée DeYoe; his daughter, Gaelen; son, Ian; son-in-law Gerben Scherpbier; and son-in-law Jake Frerk.

♦

For Tricycle Editor-in-Chief James Shaheen’s interview with Jack Engler, click here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.