The parables of the Lotus Sutra form the bedrock of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition and practice. Yet followers read these parables not for what the Buddha says about the dharma but for what the dharma says about us.

Reading the Parable of the Burning House takes time, patience, and resolve because for many, its contents can seem disturbing. Drs. Donald Lopez and Jacqueline Stone write in their book, Two Buddhas Seated Side by Side, that the Burning House is “…the most disquieting…” parable of the entire Sutra.

And yet its themes remain as relevant today as they did in the time of the Buddha. With the ubiquity of electronic devices and social media, mass hysteria and psychosis feel to be at an all-time high. Reading the parable in a modern context, it is easy to see parallels between the Buddha’s time and our own. For me, a line from a song by the popular late ‘90s band Harvey Danger comes to mind: “I’m not sick, but I’m not well.”

The Burning House parable offers an awe-inspiring tale of personal transformation and healing, freedom from fear, relief from suffering, and confidence that awakening can happen when we open our heart-mind. Another sentiment comes to mind, this time a partial line from a song by Cheap Trick: it’ll happen “if you let it.”

The Burning House is a retelling of the four noble truths. There is suffering in life, there is a cause, there is an end, and yet there is a way out if we walk through the door ourselves. At the heart of this parable is the Buddha telling us, just as he does in the third noble truth, that there is an end to suffering. All we must do is “walk through the door.” It begins with setting our intention that we want to change and experience a better life.

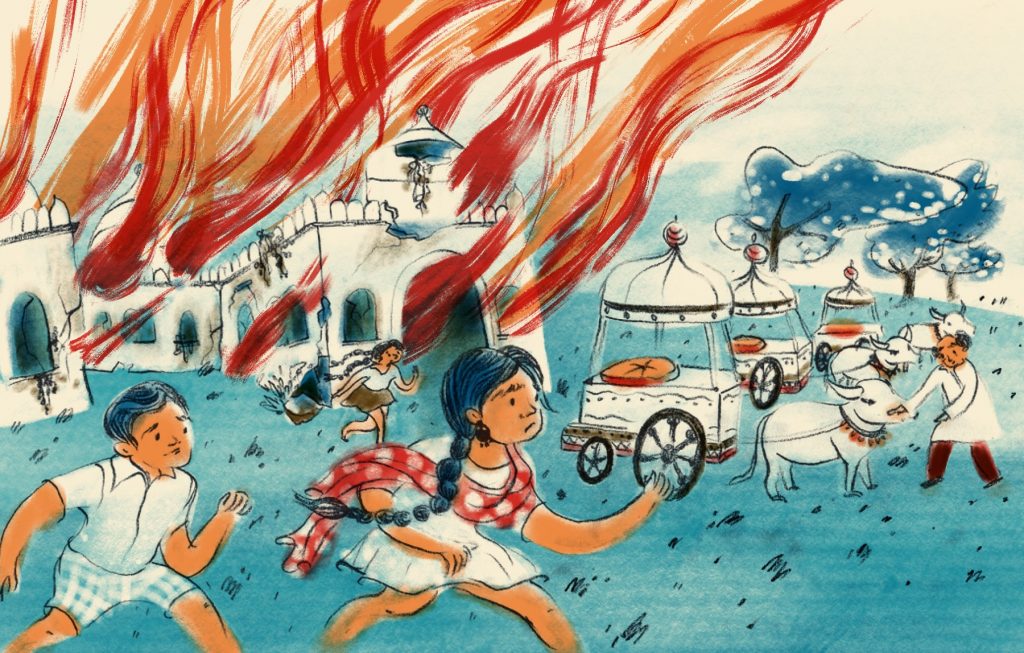

The Parable of the Burning House is being told by Shakyamuni Buddha to Shariputra in “A Parable,” Chapter Three of the Lotus Sutra. In this parable, a rich man’s decaying and demon–filled mansion catches on fire. His many children are playing inside with their favorite toys, so to get them to come out of the burning house, the rich man promises them even better treasures: goat carts, deer carts, and oxcarts. When they come out running and are free of danger, they are each given something even better: a great white oxcart.

The rich father represents the Buddha, and the children are the people of the world. The three kinds of carts represent the three vehicles the Buddha taught as skillful means:

- Voice-hearer—arhat (comprehending the four noble truths)

- Privately awakened one—pratyekabuddha (understanding the twelvefold chain of dependent origination)

- Bodhisattva (the practice of the six perfections)

The great white oxcart represents the One Vehicle. The One Vehicle is the complete and whole Mahayana teaching, and no one is excluded, not even arhats or privately awakened ones, and awakening is swift, not requiring innumerable eons of practice in order for anyone to attain Buddhahood.

Chapter Three offers these verses:

There is no safety in the threefold world.

It is just like the burning house

Full of all kinds of sufferings,

And is truly to be feared.

Ever present are the distresses

Of birth, aging, illness, and death.

These are fires

That burn unceasingly.

The conventional interpretation of the Burning House is that it’s a story of how the Buddha uses skillful means to teach his disciples: “by guiding you with my skillful means, I have caused you to be born into my dharma,” and “there are no other vehicles outside of the Buddha’s skillful means.” The Buddha’s skillful means, or One Vehicle, is the ultimate practice for liberation, and as thus, it becomes apparent that the three vehicles or paths of practice of voice-hearer, privately awakened ones, and bodhisattvas are not the final way but that the One Vehicle subsumes and illuminates them all. However, the One Vehicle does not invalidate them. Instead, it recontextualizes them as different expressions of that same One Vehicle. Each has value and merit when viewed from the whole.

This conventional interpretation is certainly true but doesn’t really tell us much, as every parable is describing the Buddha’s various uses of skillful means. The Lotus Sutra has a whole chapter on it, Chapter Two, “Skillful Means.”

So we need to look deeper to begin to understand this incredible parable and what it offers us. The Burning House is a metaphor for our lives and the world we live in. The Burning House is both a look inside our minds and the phenomena of the world we live in.

The Buddha is telling Shariputra that there is a deeper reality to experience, that the goal is not escaping this life: “I previously said that you had attained extinguishment. But that was only the end of birth and death and not the real extinguishment.”

Everyone is in fact already a bodhisattva in the process of becoming a buddha. The Lotus Sutra is considered the teaching of equality because it makes no distinctions between practitioners. There aren’t different classes of practitioners: monks, nuns, laymen, and laywomen; or voice-hearers, privately awakened ones, and bodhisattvas.

We learn early in the parable that the Buddha is in the burning house with us. The Buddha, buddhanature, and Buddhahood are always present in the burning house, or our lives and environment. Pre–Lotus Sutra teachings inform us that all phenomena arise from the mind. Yet the Lotus Sutra is teaching us that mind and phenomena are “two but not two.”

The parables present us with a range of ghastly images. These images are all metaphors for the ten worlds, or realms: hell, hunger, animality, demons, humans, gods, voice-hearers, privately awakened ones, bodhisattvas, and buddhas. These are all states of being, states of mind, various thoughts and emotions. As awful as these images sound when reading through the texts, simply consider how our negative self-talk and self-esteem affects our life’s conditions and how we interact with others. Doesn’t it feel like you are eating yourself alive when you have endless regrets, recrimination, and doubt? We will explore this idea of self-esteem in detail in the next installment on the Parable of the Wealthy Man and Poor Son, from Chapter Four, “Faith and Understanding.”

Because the Buddha is in the burning house with us, along with all ten realms, we learn that buddhanature is more than a potential or something one gains after eons of practice. We are shown that all phenomena of mind and body, all various thoughts and emotions, all forms of self and environment, all beings sentient and insentient, and all states of dependent origination are integrated in a single thought moment. The Burning House describes the mutually inclusive relationship of the ultimate truth and the phenomenological truth. Every possibility and probability of life is included in the Burning House.

The Buddha could save us, but he doesn’t. He agonizes over this. He despairs. He isn’t sure what to do. This is important. We might be inclined to gloss over this. The Buddha is opening himself up, being incredibly vulnerable. He is sharing his inner thoughts and emotions with us, letting us know these thoughts and emotions are normal, that everyone has them, even the Buddha; this reminds us that the Buddha isn’t a god, he is still human, subject to all the same ups and downs as we are. This shows great compassion.

Anyone who is a parent knows how hard it is to let their children fail when they are learning to do things on their own. The Buddha knows that if he intervened directly and saved his children, he would create a culture of dependency and control. He models for us that a teacher and parent’s role is to point the way, open the door, and offer a supportive hand when times get tough—to facilitate someone’s own personal direct experience.

The Burning House offers that we are all in the house together. We are not alone. The fear of separation begins with our first breath and cutting the umbilical cord. Our fear of being alone causes trauma, anxiety, and fear, leading to competition, discrimination, ignorance, jealousy, aggression, and war—just like the demons and animals squabbling and eating each other in the house.

“All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” –Blaise Pascal’s Pensées

In his life’s posthumous magnum opus, the Pensées, French philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal offers a wonderful insight into our aversion to self-awareness and responsibility. Bizarrely, we will endlessly distract ourselves with an innumerable manner of insignificant things and entertainment rather than face our primal fear from birth of being alone and disconnected. Psychologists have put this assertion to the test a few times. In one experiment, roughly half of a group disliked sitting quietly so much that they chose to receive an electric shock to get out of the room and exit the experiment early. Pain was preferable to insight! Our fear eats us alive, causing us to avoid that which can actually heal us. This idea about fear actually plays a central role in Chapter 16 of the Lotus Sutra, the Parable of the Good Doctor, which this series will be covering in the future. We’re so sick, we prefer the burning house. We’re so afraid and averse to ourselves that we’d rather experience the external pain of electrocution than the internal pain of our own self-reflection.

Please don’t view this parable as suggesting some form of spiritual bypassing, that we can just meditate our way out of ignorance, hatred, and greed. It also isn’t suggesting a line of magical thinking—“just sit” or “just chant.” Growing up, maturing, and especially coming into awakening takes hard work. Yet the parable is saying there is an end to suffering, and all it involves is walking through the door but that you must do the work for yourself. The fourth noble truth.

In Nichiren Buddhism, there is a concept called Bonno Soku Bodai, “Our Defilements are Awakening.” This means that only by deeply understanding and fully embracing our defilements can we awaken and become whole. Not by rejecting the various ten realms but by seeing them, recognizing them, accepting them, reflecting on them, observing how and when they originate.

Rarely can this be done on one’s own through simple self-reflection and meditation. This is why the Buddha said that the whole of a practitioner’s life must also include admirable friends. We need good friends, good teachers, even good therapists.

The parable leaves us with hope and a promise. Every time we sit on the cushion to meditate, we are stepping through the doorway of the burning house. As all great meditation teachers offer, “simply begin again.” Awakening is possible, freedom from suffering is possible. All you have to do is let it. It happens in an instant, in this very moment, in this very life, even inside the burning house.

♦

Translation from The Threefold Lotus Sutra: A Modern Translation for Contemporary Readers. Translated by Michio Shinozaki, Brook A. Ziporyn and David C. Earhart. Published by Kosei Publishing, 2019

The Parable of the Burning House, in verse, the oldest section of the Lotus Sutra:

“Suppose there was an elder

Who had a large house.

This house was very old,

Decayed and dilapidated.

The lofty halls were on the verge of collapse,

The pillars were rotting at their bases,

The beams were leaning and the rafters toppling,

And the foundation and steps were caving in.

The walls were ruined and cracked,

With plaster crumbling away.

The eaves were slanting and slipping,

And the thatched roof was in disarray.

The fences were broken and twisted,

And garbage and filth lay in piles everywhere.

Some five hundred people

Were living inside it.

Kites, owls, hawks, eagles,

Crows, magpies, pigeons, doves,

Lizards, snakes, vipers, scorpions,

Centipedes, millipedes,

Geckos, galley worms,

Weasels, raccoon dogs, rats, and mice,

And every other sort of vermin

Scurried about in every direction.

There were places stinking with excrement and urine,

Overflowing with filth,

Upon which dung beetles and worms

Swarmed together.

Foxes, wolves, and jackals

Bit and trampled each other,

Ripping apart the bodies of the dead,

Scattering bone and tissue.

Following them came packs of dogs

That fought with each other, snatching, and grabbing.

Gaunt with hunger, they skulked about,

Roving in search of food,

Fighting and scuffling,

Snarling and growling.

Such were the terrifying and degraded conditions

Into which that house had fallen.

All around and everywhere

Were goblins and ogres,

Yakshas and evil demons,

Who devoured human flesh

And all sorts of poisonous insects.

Vicious birds and beasts

Hatched and suckled their broods,

Each hiding and protecting its own.

Yakshas competed with each other

In seizing and devouring them.

When they had eaten their fill,

Their evil minds became inflamed,

And the sound of their combat

Was horrific in the extreme.

Kumbhanda demons,

Crouching on clumps of dirt,

Sometimes sprang up

A foot or two off the ground,

Floating about to and fro

And giving full rein to their sport.

They seized dogs by two legs,

Beating them into silence,

Pinning down their necks with their feet,

And torturing them for their own amusement.

Also there were demons,

Their bodies quite tall,

Naked and gaunt,

Always dwelling there,

Who emitted loud, dreadful sounds,

Bellowing for food.

Moreover, there were demons

With throats as narrow as needles,

And yet still other demons

With heads like the head of an ox.

Some ate human flesh,

Others devoured dogs.

Their hair was unkempt and tangled,

They were cruel, ferocious, and fiendish.

Driven by hunger and thirst,

They raced about crying and screaming.

Yakshas and hungry spirits,

Vicious birds and beasts,

Hungrily charged in all directions,

Peering through the windows.

Such were its perils,

Immeasurably terrifying.

This old, dilapidated house

Belonged to a man

Who had stepped out

But a short while ago,

When the house

Suddenly caught fire

On all four sides at once.

As the flames reached full blaze,

Ridgepoles, rafters, beams, and pillars

Trembled, split, snapped, and broke apart,

Falling with explosive sounds.

Walls and partitions crumbled.

Many spirit demons

Bellowed and cried loudly.

Hawks, eagles, and other birds of prey,

Kumbhanda and other demons,

Circled about in panic and fear,

Powerless to escape.

Ferocious beasts and poisonous insects

Took cover in their dens and holes.

Pishachaka demons,

Also dwelling therein,

Were so meager in blessings and virtues

That when hemmed in by the flames,

They savagely turned upon one another,

Devouring each other’s flesh and blood.

The larger of the ferocious beasts

Vied to devour the corpses

Of the jackals and their kind

That had succumbed earlier.

Acrid smoke billowed forth,

Filling the house on every side.

The centipedes and millipedes

And all the various venomous snakes,

Scorched by the heat,

Fought to flee from their holes.

Kumbhanda demons

Scooped them up and ate them.

Hungry spirits,

Their heads ablaze,

Famished, parched, and tormented by heat,

Rushed about in confusion and anguish.

Such was the state of that house,

Horrific in the extreme.

Beset by poisons, dangers, and conflagrations,

Its perils were many, not just one.

At that very time,

the master of the house

Was standing outside the doorway

And heard someone say,

‘A little while ago, all of your children

Were playing together

And went inside this house.

In their youthful ignorance,

They are absorbed in their games.’

Alarmed to hear this, the elder

Rushed into the burning house,

Intent on saving them

From being burned.

He told his children

Of its many dangers, saying,

‘There are evil demons and poisonous insects,

And the fire is spreading.

Suffering upon suffering

Endlessly comes, one after another.

Venomous snakes, lizards, and vipers,

All kinds of yakshas

And Kumbhanda demons, jackals, foxes, and dogs,

Hawks, eagles, kites, and owls,

And all sorts of centipedes,

Crazed by hunger and thirst,

Are truly to be feared.

The sufferings here are already hard to deal with,

How much more so in the midst of this raging fire.’

Because the children understood nothing of these dangers,

Even though they heard their father’s admonition,

They did not stop playing,

Being so absorbed in their amusements.

Thereupon the elder

Had this thought:

‘My children, being like this,

Increase my distress and dismay.

In this house, at present,

There is not a single thing to enjoy,

Yet all of my children,

Engrossed in their play,

Ignore my instructions

And will be injured by the fire.’

He therefore considered

Devising some skillful means

And said to his children,

‘I have many kinds

Of rare toys for you.

There are fine carts, splendidly jeweled,

Including goat carts, deer carts,

And great oxcarts,

Right now, outside the door.

All of you, come out,

For I have made these carts

Especially for you.

Take whichever you like

And play with it as you please.’

As soon as the children heard him tell

Of such carts as these,

They raced one another

To scramble outside,

Quickly reaching the open ground,

Away from the sufferings and dangers.

The elder, seeing that his children

Had escaped from the burning house

And were settled in the square,

Sat upon his lion seat

And congratulated himself, saying,

‘Now I am relieved and rejoice.

How difficult it is

To raise children such as these.

Ignorant, immature, and foolish,

They went inside this dangerous house

Crawling with poisonous worms

And ferocious goblins.

A huge fire with fierce flames

Broke out on all four sides at once,

But these children

Were engrossed in their play.

Now I have rescued them

And caused them to avoid harm.

My friends, this is why I am now relieved and rejoicing.’

Then the children,

Knowing he was comfortably seated,

All came before their father

And said to him,

‘Please give us

The three kinds of jeweled carts

You promised us by saying,

“If you children come out,

I will give you three kinds of carts

And you can choose whichever you like.”

Now is the time

To give them to us, please.’

The elder is very wealthy

And has storehouses

Full of gold, silver, lapis lazuli,

Mother of pearl, and agates.

He has made great carts

With all kinds of precious things.

They were magnificently adorned and splendidly decorated,

With railings running around them,

Hung with bells on every side,

Strung with golden cords,

And with nets of pearls

Stretched across the top.

Strings of golden flowers

Were hanging down around them.

Colorful tapestries and various decorations

Surrounded and enwrapped them.

Atop their cushions,

Made of soft silk and gauze,

Were spread

Wondrously exquisite felts

Worth thousands of millions,

Immaculate and brilliantly white.

There were great white oxen,

Stout, robust, and strong,

Of finest form and physique,

To pull the jeweled carts,

And numerous attendants

To accompany and guard them.

These splendid carts

Were given to all the children equally.

Then the children,

Ecstatic with joy,

Riding in these jeweled carts,

Roamed in every direction,

Playing joyfully

Just as they wished, without hindrance.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.