In the summer of 1989, I was 8 years old and visiting the United Kingdom with my family for the first time. As we were leaving our hotel in London, I sprinted across the road and, without noticing the traffic lights, was hit by a speeding car. The impact sent me flying several meters. My grandfather saw the whole thing and nearly had a heart attack. The police and ambulance arrived, and I was rushed to a nearby hospital. After examinations and X-rays, I was found to have only minor bruises, and the next day, I was already running around Regent’s Park.

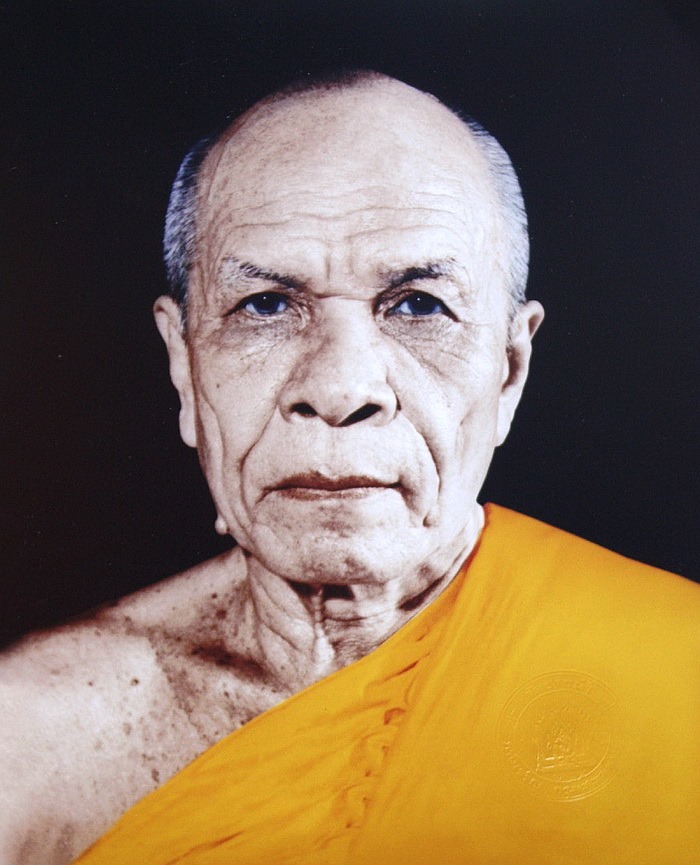

My parents believed that the amulet I wore around my neck had protected me. It had been activated at Wat Luang Pho Sot Thammakayaram in Ratchaburi province, Thailand, a temple named after one of the most influential Thai Buddhist monks of the 20th century, Luang Pho Sot Candasaro (1884‒1959). During his forty-three years as abbot of Wat Paknam in Bangkok, Luang Pho Sot introduced, developed, and popularized a meditation system called Samma Araham—also known as Dhammakaya meditation (Th.: Witcha Thammakai). Under his leadership, Wat Paknam grew from a neglected temple into a center of meditation and Pali studies that attracted monks, novices, and lay practitioners from Thailand and abroad.

After his death in 1959, his students transmitted Samma Araham meditation in several lineages, and it’s now taught at more than 200 temples and centers in Thailand and overseas. Across Thailand, his photographs and images appear in houses, malls, offices, restaurants, and cars, and his amulets remain highly sought after. As widespread as these signs of devotion are, they reflect a life that began in humble circumstances.

Luang Pho Sot was born in 1884 as Sot Mikaeonoi in Suphanburi province. In 1905, at the age of 22, he was ordained at Wat Songphinong, a temple near his family home, and received the ordination name Candasaro Bhikkhu. A few years after ordination, he came into possession of palm-leaf manuscripts of the Satipatthana Sutta (“Discourse on the Foundation of Mindfulness”). He studied them closely, and the text became so important to him that he set himself the goal of translating the entire sutta into Thai.

In Bangkok, he pursued Pali at several temples, including Wat Pho, Wat Arun, and Wat Mahathat. At Wat Pho, he turned his residence into a classroom and invited a scholarly monk to teach him and a small group of monks and novices. By the end of the course, eleven years after his ordination, he had become proficient enough to teach and translate Pali. He then ended his formal studies and devoted himself entirely to meditation, a shift that would define the next stage of his life.

Among Luang Pho Sot’s renowned teachers were Luang Pho Niam Dhammajoti (1828–1909) and Luang Pho Nong Indasuvanno (1865–1934), two respected meditation masters from his home province of Suphanburi. He also learned from Phra Sangwaranuwong (1831‒1913) and Achan Chap Suwan (1883‒1958), both lineage holders of esoteric Theravada Buddhist traditions that date back to the late Ayutthaya era (1351–1767). The teachings of these four, together with his own meditative understanding of the Satipatthana Sutta, influenced the development of Samma Araham meditation and prepared Luang Pho Sot for the intensive practice that followed.

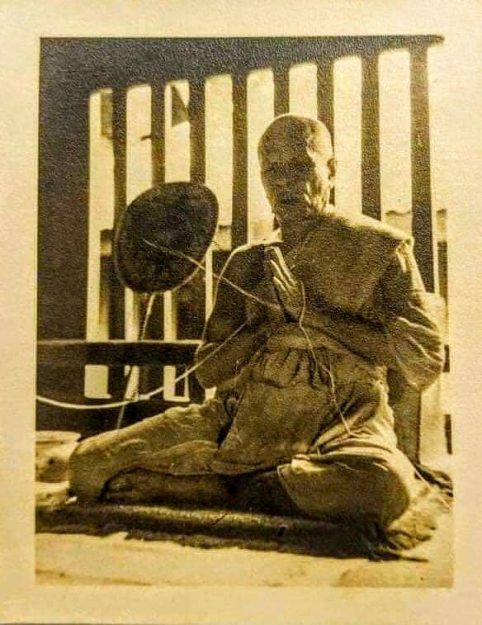

Once he was satisfied with his meditation training, Luang Pho Sot moved to Wat Botbon in Bangkok. On the full moon night of the tenth month of 1910, in his fifteenth year of monkhood, he made a vow not to rise from his seat until he had seen the Buddha’s dhamma. He begged the Buddha to grant him the simplest and smallest understanding of enlightenment, but only if doing so would not cause harm and would benefit the Buddha’s religion. That night, through continuous concentration at the center of his body, two finger widths above the navel, he awakened to the Buddha’s enlightenment. This experience later formed the basis of the Samma Araham meditation system and marked a turning point in the direction of his teaching.

Shortly after, Luang Pho Sot was appointed abbot of Wat Paknam, an old and nearly abandoned temple in the Thonburi area of Bangkok. He gradually renovated it and developed it into a center for meditation and scriptural study, giving equal emphasis to both. It was, however, Samma Araham meditation and the temple’s amulets that brought him national prominence and established Wat Paknam as an important site of practice.

Years later, Thailand’s prime minister allowed the Japanese army to occupy Thai territory and, in 1942, declared war on the United States and Great Britain. This led to increased taxes, inflation, shortages of goods, and allied bombings. During this difficult period, Luang Pho Sot turned Wat Paknam into a shelter and dedicated the merit generated from his meditation to the protection of the local people. Many people traumatized by the war sought help at the temple, some with serious illnesses, and he would provide food and his own traditional medicinal remedies. As wartime pressures increased, his role at Wat Paknam expanded alongside the community’s reliance on him.

Before the construction of Wat Paknam Scriptural School, monks and novices had to travel to other temples in Bangkok to study. But after the three-story building was completed in 1950, with room for more than a thousand people, the temple quickly became a center for Pali and Buddhist studies. Its rapid growth and popularity provoked hostility among monks and laypeople who supported other temples in the area. They spread false rumors, reported those rumors to the head of the Buddhist order of monks in Thailand, and sent police and monks to inspect his temple. When none of these efforts succeeded, they hired a gunman. As Luong Pho Sot was walking from the school to his dwelling one day, three bullets were fired. Two narrowly missed him, passing through his robes, and one struck a layman in the cheek. The man suffered a severe injury and narrowly escaped death. These attempts, however, did not deter Luang Pho Sot, who continued to spread his meditation teaching and develop Wat Paknam despite the hostility.

In 1957, Luang Pho Sot was given the monastic title of Phra Mongkhon Thepmuni, meaning “Venerable Divine Sage of Auspiciousness.” As the number of monks and novices grew, he took responsibility for providing their food, and in 1959, he built a dining hall and a kitchen large enough to accommodate 600 monks and novices. This arrangement was unique in Thailand at the time, as most monks had to go on alms rounds every morning. By establishing the dining hall, he wanted the monks and novices to spend more time studying and practicing meditation without having to worry about begging for food. He also carried out many forms of social work, including establishing a community school for poor children and providing accommodation for the elderly.

Toward the end of his life, he became nationally known for his amulets, which were given to those who donated to the school’s construction or practiced meditation at Wat Paknam. These amulets are considered unique by believers, as they are said to derive their power from cultivating merits through the practice of Samma Araham meditation. Luang Pho Sot died at Wat Paknam in 1959 at the age of 75, having been a monk for fifty-three years.

More than six decades have passed, and the legacy of Luang Pho Sot continues to thrive at temples and centers around the world. I first met my teacher, Luang Pho Sermchai (1929–2018), at Wat Luang Pho Sot Thammakayaram. He was the creator of the amulet I wore in London. Luang Pho Sermchai was a third-generation Samma Araham teacher, and I consider myself incredibly fortunate to have met him early in my life and to have studied with him for many years. During retreats, he took great interest in my progress in meditation and my education, often inviting me to his office to discuss the Buddhist teachings I had learned from my professors in the UK. In studying with him, I saw how Luang Pho Sot’s lineage continued in the quiet attention teachers give to their students, one generation after another.

Basic Level of Samma Araham Meditation

The beginning stages of Samma Araham meditation may be practiced according to the following instructions.

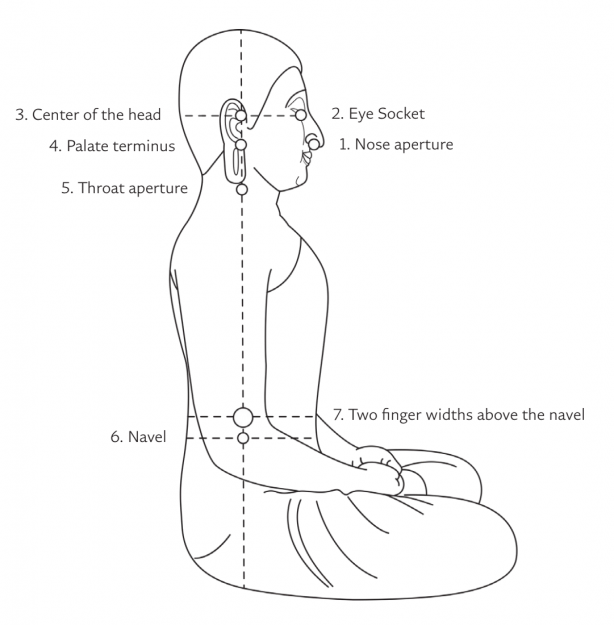

The meditator visualizes a clear crystal sphere, the size of an eyeball, entering the nostril (first base)—the left nostril for women and the right for men—while repeating the mantra samma araham three times and being aware of their breath going in and out of the body. Samma Araham, which in Pali means “right” and “enlightened/perfect one,” refers to the Buddha’s wisdom and purity. Then, very slowly, the crystal sphere is visualized moving to the eye socket (second base)—the left eye for women, and the right for men—and again samma araham is repeated three times. Then they move the crystal sphere to the center of the head (third base), then to the back of the palate (fourth base), the throat aperture (fifth base), the navel (sixth base), and finally two finger widths above the navel (seventh base). The words samma araham are repeated three times when the sphere is moved to each base. The meditator is to be aware of their breath all through this exercise.

When the crystal sphere is at the seventh position, the meditator is to draw their mind to rest at the center of the sphere. The more experienced meditator can start by visualizing the sphere directly at the seventh base.

The next step is to keep the mind still at the center of the sphere at the seventh base. The mind consists of sensing (vedana), remembering (sanna), thinking (sankhara), and knowing (vinnana) joined together. When the mind is completely still at the center of the body, a bright sphere the size of the sun or moon will appear there. The meditator then stops visualizing and reciting the Pali words. It is said that the meditator will see their mind or the dhamma sphere.

Inside the mind, there are five points, which consist of five basic elements: (1) water element, front; (2) earth element, right; (3) wind element, left; (4) fire element, back; and (5) space element, center. The water element governs the body’s fluidity. The earth element controls the solidity; the wind element, the internal movement of gases; the fire element, the body temperature; and the space element, the spaces in the body. Inside the space element lies the consciousness element, which controls the consciousness.

♦

Adapted from Seeing the Bodies Within: Exploring the Samma Araham Practice of Theravada Buddhism by Potprecha Cholvijarn. © 2025 by Potprecha Cholvijarn, with permission from Shambhala Publications.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.