Last month the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened “Mandalas: Mapping the Buddhist Art of Tibet,” a major exhibition including a contemporary site-specific installation and more than a hundred classical Tibetan Buddhist artworks. This happened just around the time the Quai de Branly Museum in Paris made the cynical and dubious choice to revise labels of Tibetan artworks by replacing “Tibet” with the Chinese name “Xizang.” Taking a different approach, Paris’s Guimet Museum opted for “Himalayan” in the place of “Tibetan.” These changes seem to demonstrate political pressure shaping cultural institutions. Nearer to the Met, the Rubin Museum in New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood recently closed its doors after twenty years of curating exhibitions intended for broad public audiences. (Author’s note: I worked at the Rubin from 2014–2016.) Many will miss the opportunity to spend time with the mostly Tibetan Buddhist artworks shown at the Rubin, and many might regret taking the collection for granted all these years, even among those who are acutely aware of the unjust conditions under which some of this art has ended up on museum walls. In recent years, activists and critics have called for more transparency around provenance and spurred discussions about what repatriation might look like in Tibetan diaspora communities. In this charged context, the Met’s “Mandalas” show, which is on view through January 12, has the potential to reach larger audiences than similar exhibitions have reached, and it offers ample opportunities for reflection, discernment, provocation, and dialogue about what it takes not just to look at but also to see a work of art.

Entering the crowded lobby of the Met in mid-October, I asked a guard where to find “Mandalas,” and she told me, “Straight back, where the Dutch Masters used to be.” Following her outstretched hand pointing in the direction of the Robert Lehman Wing’s central atrium, I happened to find the artist Tenzing Rigdol deep in conversation with Tim McHenry, longtime Director of Programs and Deputy Executive Director of the Rubin and a dear friend of mine. In a synchronicity resonant with the Buddhist concept of “dependent arising,” or tendrel, they invited me to join them in touring the atrium where Rigdol’s Biography of a Thought is on view at the center of the “Mandalas” exhibition.

The curator Kurt Behrendt invited Rigdol to propose an installation for the atrium in 2019, before they saw the pandemic coming. After the work was commissioned in early 2020, the pandemic hit, and Rigdol spent years in Nepal producing the work, which is far more than a painting; four massive and explosively vibrant panels surround a central platform adorned with bright colors, American Sign Language “mudras,” or ritual gestures, and lines of poetry communicated in braille. The Nepali carpets emblazoned with clouds and lotuses integrate the ground beneath visitors’ feet into the installation. McHenry and I reflected on how in one panel, the two-dimensional braille that Rigdol painted provokes the question of what each of us can and cannot see, whether reading braille with one’s fingers or encountering it with one’s eyes. Those who read braille might not find it there, flat and high enough on the wall to be generally out of reach. And many of those who can see the braille on the wall likely cannot read it. Likewise, only those who understand ASL will be able to perceive the communication of the creative gestures directly. Ridgol smiled at us encouragingly, happy to muse on the potential interpretations together. Throughout the installation, Rigdol contemplates and questions conventional concepts of accessibility and esotericism, ability and disability, ignorance and insight, as juxtapositions evoking Buddhist teachings on nonduality.

The murals are rich with lively detail, including the image of a polar bear adrift on a melting ice floe, one of several visual reference points that simultaneously serve as reminders of pressing crises and unheeded warnings. A semiautomatic weapon appears as a chillingly familiar reminder of gun violence in the United States, and a portrait of George Floyd appears beatific in the posture of Maitreya, the Buddha of the future. These familiar cultural touchstones help orient the visitor to the perhaps less familiar elements of the mandalas the work references. Glimmers of traditional Tibetan Buddhist iconography and adornment appear deconstructed. The work is as decorative as it is philosophical. It evokes classical Tibetan Buddhist motifs and esoteric symbols while at the same time commenting critically on pressing sociopolitical issues of the global here and now. As in the architectural space of a mandala, in which the ritual ground is prepared in order to invite an assembly of deities, Biography of a Thought is a space prepared for the ritual of seeing not only with one’s eyes but also with the full range of senses, including the mind. Its constituent parts are distinct and discernable, and together they engage the viewer in an impactful whole. All this is partly in service of what Behrendt describes as the “methodology for looking at art” that Rigdol conveys through the work. Whereas in a Buddhist mandala the central platform would be a lotus throne arranged for the main deity, in Rigdol’s work the platform suggests a vacancy left open at the center. The work poses the questions: What does it take to really “see,” and what are the lessons and skills one needs to find one’s way?

Situated as it is in the central atrium, Biography of a Thought acts as a contemporary visual interlocutor for the far more numerous classical works in the exhibition, which were produced in Tibet, Nepal, Kashmir, and the Ganges River basin of India between the 11th and 15th centuries. The architecture of the atrium has a marked similarity to the basic layout of mandalas as “ritual diagrams that map the universe.” Moving outward from the atrium, which is filled with sunlight and vibrant color, the surrounding galleries are dimly lit—the mood shifts to a more interior and somber tone, and the predominant palette shifts from electric blues to deep ochres and reds. The exhibition is motivated by a pedagogical drive to help unfamiliar viewers gain the necessary skills to not just look at but also to see Tibetan Buddhist art meaningfully, as an expression of a living tradition. This intention remains implicit, and as a teacher, I wished for the connections between themes, sections, and individual objects to be made more explicit. The artworks and ritual implements, many of which are stunning and rare, are arranged according to categories that correspond to some constituent elements of Tibetan Buddhist art in general and mandalas in particular. These categories are designated as “teachers and texts; protectors; bodhisattvas as spiritual guides; tantric deities offering access to enlightenment; and mandalas as diagrams of true Buddhist reality.” Given how broad these categories are, some visitors might experience the arrangement of artworks as appearing somewhat random—why is this bodhisattva here rather than there, and why are these two images placed together? In an important sense, all of these works are complete unto themselves. Without explicit didactic interventions, it is hard to relate to a portrait of a teacher or an image of a bodhisattva as illustrating part of another complete image such as a mandala.

As tools for guiding visitors to notice constituent parts of whole images, the most effective work is done by the objects that might be easiest to overlook. These include exquisite illuminated manuscript covers, jeweled ornaments and amulets made of turquoise and gold, musical instruments, armor, and ritual implements displayed in vitrines. These objects really are parts of a whole, so they work well in that supporting capacity. Take note of the lovely “Interior of a Book Cover illustrating Manjuvajra Embracing His Consort, with Attendant Lamas,” and “Pair of Manuscript Covers with Buddhist Scenes.” There is so much to look at and see in these carefully crafted book covers. There is also an extraordinary set of “Initiation Cards” made from opaque watercolor on paper. These intricately painted cards are a delight to pore over, and as a set, they offer clues about how these objects were and still are used by Buddhist practitioners in ritual contexts. The humbler elements displayed in simple vitrines also reflect the collaborative nature of the show, as experts from across and beyond the Met contributed to these sections on manuscripts, ornaments, musical instruments, and arms and armor.

Each mandala is a universe unto itself, and indeed the more you look, the more you see.

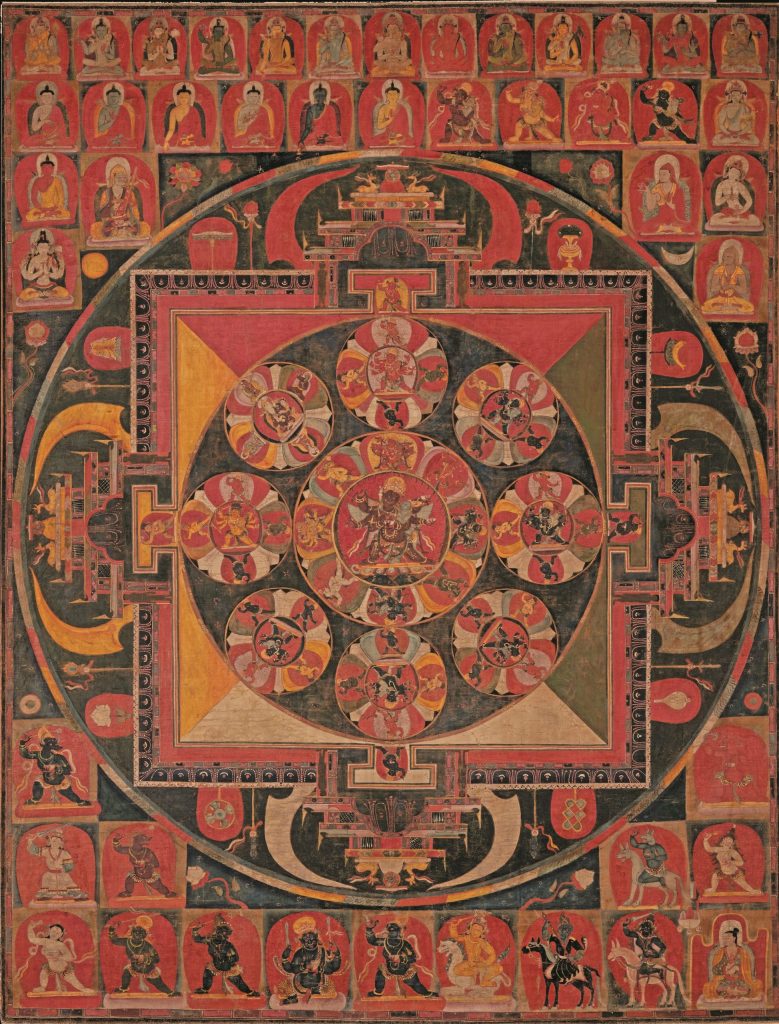

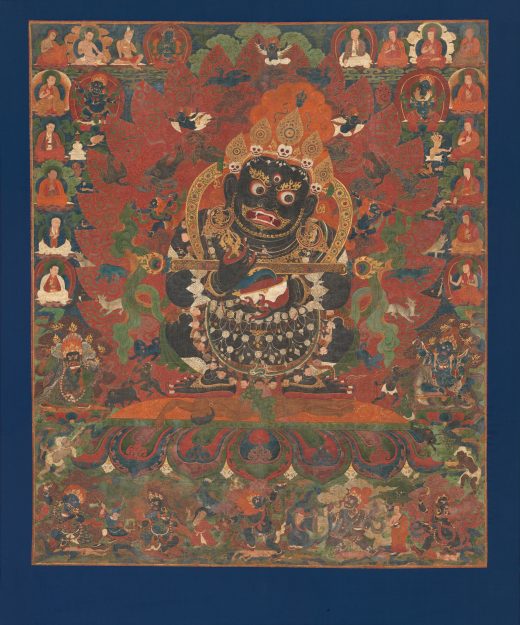

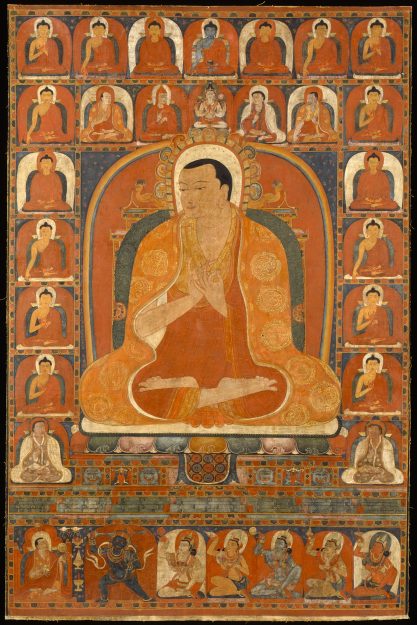

The titular mandalas, displayed in a single gallery, are the heart of this expansive exhibition. Each mandala is a universe unto itself, and indeed the more you look, the more you see—from the sparkle of gold, to the subtle sense of humor of the artist, to the floating body parts evoking the idea of impermanence, to the graceful gestures and elegant expressions of enlightenment. Viewed together, a distinctive approach to perspective becomes evident, reminding us there is no “up” and “down” in space. The large silk tapestry of Vajrabhairava Mandala from the Yuan dynasty is a marvel of the craft. Some of the oldest mandalas, painted in Nepal and Central Tibet in the 11th and 12th centuries, are remarkably detailed and well-preserved, prompting visitors to think about the many hands and worlds they must have passed through along the way, not always peaceably. Beyond the mandalas, some stars of the exhibition include the Mahasiddha Virupa, who appears larger than life and wielding his power to hold up the sun in a 13th- century painting from Central Tibet. (The story goes that he stopped the sun from setting in order to delay ending a day of drinking and having to pay up.) An image not to miss in the Tantric Deities section is Hevajra with the Footprints of the Kagyu Patriarch Tashipel, also from the 13th century. The late-15th-century painting of Guhyasamaja from western Tibet will take your breath away, and The Bodhisattva Manjushri as a Ferocious Destroyer of Ignorance stopped me in my tracks with his weighty stance. Images of Palden Lhamo and Mahakala stand out in the Protectors section. Among the teachers, the Portrait of Shakyashribhadra and the Portrait of a Kadam Master quietly evoke devotion for an idealized enlightened lama.

Like all these beautiful works of art, much of the classical Buddhist art of Tibet and the Himalayan region is esoteric, and that means it is challenging to grasp and understand fully. But one need not be an expert to appreciate these remarkable expressions of human experience and creative cultural production. To return to the underlying question driving the exhibition, what does one need to know in order to really see this art? These works are very much alive and active for contemporary Buddhist practitioners, even imbued with the presence of enlightenment, and their many layers of meaning and connection are not sealed in the past. To deeply engage this art, in a Buddhist sense, requires initiation, expert guidance, familiarization through practice, and commitment. But to see this art in the context of the museum, visitors might find themselves more capable than they expect, and the formal logic of the compositions goes a long way in guiding attentive viewers. “Mandalas: Mapping the Buddhist Art of Tibet” aims to provide a map for approaching the Buddhist art of Tibet, allowing for its complex historical, cultural, political, religious, and aesthetic contexts. Reflecting again on tendrel and the ongoing interplay of causes and conditions, visitors will see that beauty matters, politics matter, history matters, economics matter, gender matters, language and context and resources all matter. With all this in mind, I encourage you to go and look, take your time, pay attention, loosen your expectations, and see what you find.

“Mandalas: Mapping the Buddhist Art of Tibet” is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through January 12. Visit the Met for more information.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.