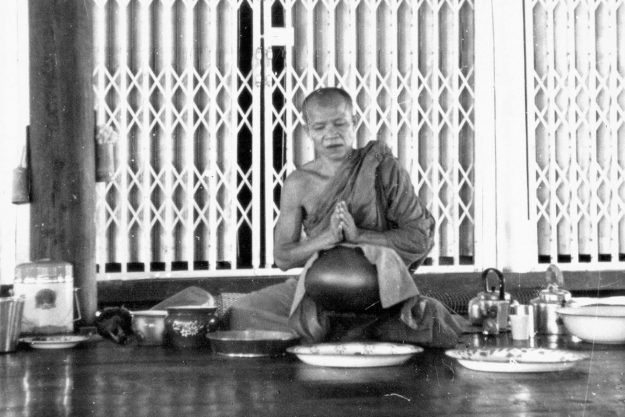

Living with other meditators showed me many strategies for eliminating the kilesas (afflictions, unwholesome mental states). One I learned at Baan Taad was fasting. In the beginning, I just noticed that some monks sitting near me kept disappearing from time to time. I thought they had gone home or were attending to personal business somewhere. When I asked another monk about this, he said they were fasting. When that happened, those who were fasting did not have to come out for the normal activities, such as going out for morning alms or participating in joint tasks. They only had to take care of their personal space because they were focused on solitude, not having to be distracted by sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and tactile sensations. When fasting, they would only meditate.

When I first read Luangtaʼs book Paṭipadā – Venerable Ācariya Munʼs Path of Practice, he explained the benefits of fasting, but I never tried it while meditating at home, thinking that I was pretty good to be able to eat only one meal a day. However, when I saw other monks at the monastery fasting, I was encouraged to try it to see its effects.

Fasting sets up the situation of suffering from hunger. When hunger has arisen, there are two ways to quell it: finding something to eat or stopping our mind. Fasting means that we would not find food to quell the hunger, so the only way to do it is by meditating to gain peace of mind, because 90% of hunger comes from the mind, not the body. The body only provides a tenth of the intensity of the hunger, but if the mind even begins to think about food, saliva already begins to flow.

So when we fast, it is like a boxer who enters the ring, no longer just hitting the punching bag. We are now fighting with passions and desires, so we cannot take it easy. We have to be very strict with sitting and walking meditation. If we get tired when doing sitting meditation, we need to get up to do walking meditation instead until we are worn out, and then go back to sitting meditation again. Fasting also helps us to try harder because then we are like a boxer in the arena: you cannot just stand around awkwardly, but have to bring out all your skills and techniques to fight in order to not get knocked down.

Fasting helps us to try harder because then we are like a boxer in the arena: you cannot just stand around awkwardly, but have to bring out all your skills and techniques to fight in order to not get knocked down.

When I fasted and created a condition of suffering from hunger, I had to find a way to fight it, and that was only through meditation. Sitting meditation could calm my mind and my hunger would go away so that I could do walking meditation with ease. However, after a little while, the strength of my samadhi would wane and thoughts about food would begin to proliferate again, so I had to go back to sitting meditation until the mind calmed down and the hunger disappeared again. I would sit until my body was tired, change to walking meditation, and continue to meditate like that all day and all night. I could not lie down to go to sleep because hunger would come back, so I did not want to sleep. My mind had to be continually controlled by mindfulness and wisdom. Sometimes I had to consider food as being disgusting so I could stop imagining things about food.

When I considered it like this, the desire to eat food would reduce. Or sometimes, I had to pressure the mind to resist the thoughts and bring out the dhamma, which meant developing sati (mindfulness), samadhi (concentration), and panna (wisdom). But, when I relaxed my efforts, the kilesas came out again and went out of control.

For example, on days that I got sleepy after the meal, when I returned to the kuti, I wanted to put my head down on a pillow instead of doing walking or sitting meditation. If I started to do sitting meditation, after a short time my head would drop. In this way, fasting supported my perseverance. I would alternate my routine and fast sometimes for three days, sometimes five days, then go back to eating for two days, and then back to fasting again. Meanwhile, I would watch my body because too much fasting can hurt the stomach.

Another good thing about fasting was that before I began doing it, I would feel hungry in the evening and start to think about food. However, once I had been fasting for a while, I would stop thinking so much about food because if I could go without food for three or four days and still be okay, not eating anything in the evening should not be a problem. Also, after fasting for three or four days, everything would taste good, even just plain rice. So fasting was good for me because it helped me meditate diligently.

Over a period of two years, I used a fasting technique where I would alternate between fasting and eating. I tried to see how long I would be able to fast and the longest was nine days, after which my mind was not so good. It didnʼt think about meditating and just wanted to sleep because I had no strength. I was exhausted. It didnʼt want to meditate, it only wanted sleep. At that point I reminded myself that I should not fast to beat my own record, but only to boost the meditation. If I was too tired to meditate, then I should not be fasting. I eventually found that fasting for five to seven days worked best—for the first three days the hunger was very bad but, after three days, the hunger pains would subside.

For the fasting monks, Luangta would allow them to drink some milk. Back then, there were no milk boxes. We would have sweetened condensed milk mixed with Ovaltine. One drink per day prevented serious exhaustion. In the afternoon we were allowed to have a pana (drink), which was usually a cocoa drink, or sometimes Luangta would send chocolate to us fasting monks—but never to the non-fasting monks. So, during my fasting periods, I would get some chocolate. Another benefit of fasting was that I did not have to meet the “Tiger” (as we referred to Luangta) at the sala because we had to be on our guard all the time during the meal. Sometimes, when monks did not want to face the “Tiger,” many would choose to fast. Especially during the rains retreat, sometimes half of the monks would disappear from the sala to fast so that they could avoid the Tigerʼs growls.

♦

This article was excerpted from Phra Ajaan Suchart Abhijato’s autobiography, Beyond Birth, and was republished with permission from Phra Ajaan Suchart Abhijato at Wat Yannasangwararam.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.