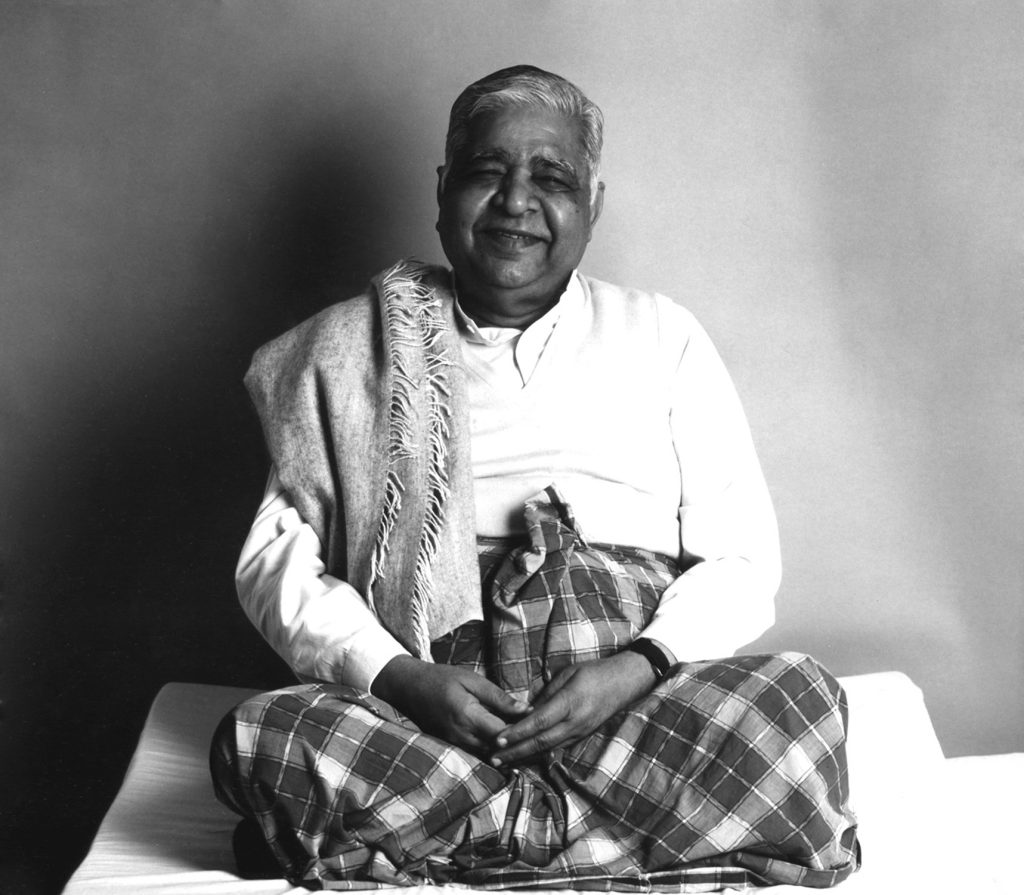

S. N. Goenka, leader of an enormously popular worldwide insight meditation (vipassana) movement, died on September 29 of natural causes in Mumbai, India. He was 90 years old.

Goenka came from a family of Indian extraction, but was born in 1924 in British Burma, a Theravada Buddhist culture. Seeking a cure for his debilitating migraines, Goenka consulted the lay meditation teacher U Ba Khin at his International Meditation Center (IMC) in Rangoon in 1956. While U Ba Khin refused to teach meditation for the purpose of curing headaches, the teacher’s demeanor nonetheless impressed Goenka. “I said to myself, ‘Look, this is another religion, Buddhism. And these people are atheists, they don’t believe in God or in the existence of a soul! If I become an atheist, then what will happen to me? Oh no, I had better die in my own religion. I will never go near them.” Still, he sensed an atmosphere of peace at the IMC that he wanted for himself. Eventually, he overcame his initial concerns and undertook a retreat.

By his own account, the ten-day course transformed him, showing him what he called “the dark chamber of the mind within . . . full of snakes and scorpions and centipedes, because of which I had to endure so much suffering.” He understood this nature of mind to be typical of all unawakened people. Meditation was, he realized, the way to cleanse the mind, to let light in and clear away the vermin. Vipassana was not part of a religion, then, but a nonsectarian technique available in the here and now to help all people, whether Hindu, Buddhist, Christian, Muslim, or anything else. His reservations dissipated, and he became convinced that “[the Buddha] never taught any ‘ism’ or sectarian doctrine,” but rather “something from which people of every background can benefit: an art of living.”

Goenka studied another 14 years under U Ba Khin while conducting business in Rangoon and supporting his family of six sons. His own status as a layman would become part of the appeal of his movement. Just as Goenka stressed that vipassana, as a technique, was applicable to people of all faiths (or none), he also insisted that it was fully available to people living in the everyday world. In 1969, having been designated a teacher by U Ba Khin, he emigrated to Mumbai, India, and began to teach meditation there full time, first to his family but soon to others as word about his teachings spread.

Goenka presented meditation as the fundamental teaching of the Buddha. He matched his emphasis on vipassana as the heart of the Buddha’s teaching with an emphasis on the technique of observing the sensations of the body, which he understood to be handed down without any change whatsoever from the time of the Buddha:

Five centuries after the Buddha, the noble heritage of Vipassana had disappeared from India. The purity of the teaching was lost elsewhere as well. In the country of Myanmar, however, it was preserved by a chain of devoted teachers. From generation to generation, over two thousand years, this dedicated lineage transmitted the technique in its pristine purity.

This idea that meditation was what mattered most among the Buddha’s teachings, combined with the notion that it was open to all, detached such practice from any particular tradition. In fact, it made insight meditation a separate tradition in its own right.

Goenka tied this conception of an unchanging technique as the quintessence of Buddhism to a highly standardized method of instruction. Indeed, although there are hundreds of assistant teachers throughout the world who lead courses with the help of volunteers, even today the main sources of instruction during retreats are videotapes and audio recordings by Goenka himself. A commitment to never charging fees for courses, in addition to a highly standardized form of practice, supported his vision for accessible meditation.

The lack of any fees in particular made retreats accessible to all classes of people. In the 1970s this drew many Westerners on the “hippie trail” and increased Goenka’s popularity and renown. Some Westerners who took courses would go on to become influential meditation teachers, including Joseph Goldstein and Sharon Salzberg, founders with Jack Kornfield of the Insight Meditation Society (IMS). Goenka’s organization of courses, shaped by his teacher U Ba Khin, influenced the structure of retreats in the West at IMS and elsewhere, with alternating periods of personal and group practice and periodic group interviews by teachers.

Goenka’s transformation of vipassana into a standalone movement has had a profound effect on general conceptions of Buddhist practice in the modern world. By presenting meditation as a universal art of living, Goenka enabled practice to further permeate societies as a secular technique, especially in Europe and North America. His later efforts, such as founding a research institute to study vipassana’s social effects and, in 2002, touring 35 North American cities to spread the word about meditation, further reinforced the popular message that meditation is nonreligious. His practical presentation has influenced many, particularly in the West, to see vipassana as essentially about one’s current life and how it is lived.

Goenka’s view of vipassana as an art of living extends to the very end of life, for to learn how to live is to learn how to die: “Vipassana teaches the art of dying: how to die peacefully, harmoniously. And one learns the art of dying by learning the art of living: how to become master of the present moment.”

Goenka is reported to have passed away peacefully in his home. That his life ended in such an everyday setting fits with his vision of meditation. “When your own death comes, observe it, at the level of sensations,” writes Goenka. “Everyone has to observe one’s death: coming, coming, coming, going, going, going, gone! Be happy!”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.