In 1985, Seta Manoukian left her hometown of Beirut, the city she had identified with as intimately as that of her own body—its streets, her skin, its cries, her voice. After living through ten years of a bloody civil war, she had seen people for who they were—the charitable and the greedy, all luridly exposed before the shock of explosions and gunfire. Fear set in as some of her fellow colleagues at the Lebanese University where she worked suffered kidnappings or sometimes worse. Earlier, she had flouted shootings and bombings to attend parties and dinners as a popular painter and teacher of art, but soon even these public excursions began to feel too risky.

As a burgeoning artist in Lebanon, she had shown exceptional potential at an early age, going on to take private lessons with the well-known Lebanese painter Paul Guiragossian at just 15. In 1963, she won first prize in an art competition organized by the Italian Embassy and received a three-month scholarship to study art in Perugia, Italy, staying abroad afterward to study at the accredited Accademia di Belle Arti in Rome.

When Manoukian returned to Beirut in 1967, she began teaching at a high school while continuing her painting, despite the threat of armed conflict encroaching around her. That same year, she had her first solo show at Galerie Alecco Saab, and, simultaneously, became involved with the politically committed left-wing intellectual and artistic community of Beirut. When the Lebanese Civil War broke out in 1975, Manoukian was active on many levels—painting, creating political posters, teaching at the university, and working with children in impoverished neighborhoods, while also publishing two books about her work with children.

While her work from this period is often of the city she called home and the people and spaces she knew and loved, something inside of her knew that she hadn’t yet fully found her voice. But then, on one particularly auspicious occasion, she happened to pick up a book on mathematical theory, where one concept would alter the course of her artistic and spiritual path: the concept of oneness.

It is clear, even in her early self-portraiture, that she was seeing past superficial appearances into a deeper part of her “real self.” Every stroke of paint was an investigation of personal identity. Later, after embracing her spiritual path, she would come to see the white canvas as a boon of inspiration, the source of emptiness from which all springs into being as form, individuated, discernible, yet no less bound to universal holism. As Manoukian puts it, her interest lies in the space between objects. In her more figurative work, including what she calls her T-shape series, Manoukian juxtaposes one single body at a time with its mirror image, often perpendicularly, evoking the pose of a reclining Buddha. To her, verticality and horizontality are metaphors for life and death, the contrast of daily consciousness and eternal union.

As Lebanon’s Civil War dragged on, Manoukian became increasingly anxious, and, in 1985, moved to California to continue her work as an artist in exile. While the balmy shade of Los Angeles palms first proved a refuge, the sociocultural isolation soon transformed her extroverted, creative outlook into one that teased out her more contemplative, philosophical leanings. Restless in the US, Manoukian traveled to India, ultimately spending time in the presence of Sathya Sai Baba and his disciples. Returning to California, she met Sri Lankan monk Bhante Lakkana, beginning what would become a serious, lifelong meditation practice at the LA Buddhist Vihara. Her journey then continued abroad in Sri Lanka, first at a Theravada Buddhist monastery outside of Colombo under the guidance of teacher Pemasiri Hamdruo, who ordained her as a nun in 2005. She then stayed in Sri Lanka at a retreat center for ten months, and, in 2006, lived in South India near Bangalore for a year and a half.

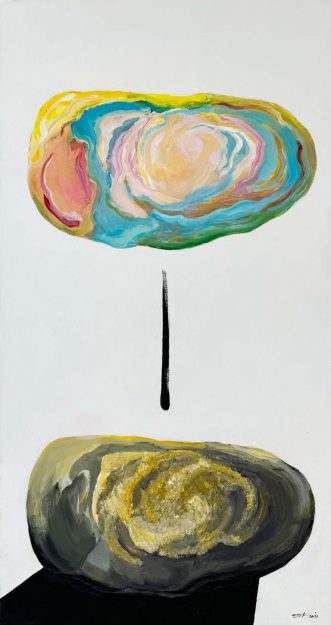

In 2007, she returned to California, where she met her Tibetan Buddhist teacher, the Venerable Lama Chödak Gyatso Nubpa Rinpoche, who gave her the dharma name, Ani Padma Tsul T’hrim Drolma. It was during this period that Manoukian stopped painting entirely, as she felt unable to combine the two intensive practices. What followed was a decade of spiritual training in the Vajrayana tradition of the ancient Nyingma heritage, frequently going on retreats to Pema Dawa in Tehachapi, California. And then, in 2016, after a ten-year hiatus and a full devotion to her Buddhist practice, Seta Manoukian, as Ani Pema Drolma, returned to painting. Although following the Vajrayana, which is steeped in a rich and often ornately detailed visual culture, Drolma’s artwork is noticeably sparse and minimalist. Her enduring gift is to accentuate the spaces between objects, the whiteness of blank canvases that, to her, are the spatial equivalent of silence. She is increasingly drawn to sensual vacancy, to the point where, as she says, her final artwork might appear just the way she started before ever pressing a brush against a surface— empty and yet also full.

Tricycle contributor Matt Hanson spoke with Manoukian by phone about her life, artistry, and path to the dharma.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your early paintings indicate that you were focused on the space between objects. How was your initial interest in art part of your spiritual quest? When I was in Rome, at the Accademia di Bella Arti, we had a model, and I noticed that I was more interested in the space between any object or between the model and her background. It was instinctual, that I was looking for the shape of the void. I was looking at the shape of the empty spaces. This continued, until now, of course. Now, I understand. I became a Buddhist because I was looking at all those spaces between objects.

Your early self-portraits seem to evoke more than what appears on the surface, as if you were searching for truth behind the superficial. When I came back from Italy, I wanted to start painting, and I thought, “How am I going to start painting. I’m just me, why would my work be valuable?” I went in front of a mirror. Again, it was instinct. I started looking at my eyes until all thoughts vanished. And then I knew right away what I was going to paint.

Later, I started looking at an empty wall. I thought it’s the same thing if I look at an empty wall. And then, after that, I knew what to paint as soon as I was looking at an empty wall. And then I didn’t need the empty wall. It has to do with empty space and emptying the mind. From there I would know what to paint.

Did your experience returning to Lebanon have an effect on your more introverted approach to art and life? On the streets of Beirut everybody was talking about politics. I was not thinking about politics at all because I was living happily in Italy. My family, they talked about the Armenian genocide. But, apart from that, I was not thinking at all about politics.

Suddenly, I was listening to what was happening in the world, in Latin America, in Africa, in Palestine, et cetera. And I was horrified.

I had a breakdown. Anxiety, boredom, and emptiness were inside of me. I was painting myself in the mirrors of my room because I wanted to know myself. I think that the body shape we have and our face is very much connected with the shapes that we paint. There is a connection between the shape we have and our personality, and also how we see shapes.

So I got to know myself. I did a painting where I have a face that was in a rage. After two years, I painted myself totally surrendering and totally in meditation, with white space around me.

After that, just before the war started, there was a book. Somebody forgot a book in our house. And I opened it. It was on mathematics. It was saying everything is one. I read it. The next day everything was light, illuminated. I was in love with everybody. It went on for three days. And after that, all the colors came back, really strong colors came back into my paintings. Before that, it was all grays and browns. Then all the colors came back and the war started, but I was happy.

Of course, I was crying, because it’s extremely sad. But overall, I was very, very happy, and without fear.

What finally made you decide to leave Beirut for the US? This went on for ten years, until ’85. I’d also like to say that I tried to help as much as I could during the war—teaching children, volunteering. And after ten years, one day there was no bombardment, nothing, and yet a huge fear came over me. I don’t know from where.

And I was fed up with all of the analysis, people that were analyzing what was happening and doing discourses. I was thinking that I have to get out of this or that, maybe there was something else I should learn or discover.

I came to Los Angeles. Beirut was really my town, where I was born. I liked everything in Beirut—people, houses, streets. It was like I had oneness with the city of Beirut. I have a painting where the street is my skin, feeling that the bombs were falling on my skin when they were coming down on us.

When I arrived in Los Angeles, I could not paint anymore. I could not paint paintings because everything was new for me, totally different. I started painting what I understood about nature, our bodies, our blood.

How did you first encounter Buddhism in Los Angeles? I met a group of people. Somebody told me there is somebody who thinks he is God, and they are having a meeting if you want to go. I thought, “Yes,” because, with a bunch of cuckoos, let’s go and have fun, you know?

As soon as I entered the room, I thought, “Oh, my goodness, I am home.” All the tensions that I had totally disappeared. This friend of mine said, “What’s happening, Seta? Your face has totally changed. What is happening?”

They were Sai Baba devotees. I went to India many times after that. And then somebody told me there is a monk, a Theravada monk, who is teaching meditation.

I did five years of meditation with him, and then I went to Sri Lanka and became a nun. I stayed for one year and then went to India. I came back, and somebody came to our house, knocked on the door and said, “There is a monk, a Tibetan monk. Do you want to meet him?” I said, “Yes, of course. I’d like to meet him.”

I went with the Vajrayana monk, who is my root lama, Lama Chödak Gyatso Nubpa Rinpoche. And I asked him a question, and he went into samadhi, and I went into samadhi. I asked him another question, and then he went into samadhi again, and I went into samadhi. It was three, four times like that.

This was 2007. And then he passed away in 2009, and I am still continuing with his sangha. He is my dhamma.

Can you explain more about your early Buddhist practice? A Sai Baba devotee told me about a monk teaching meditation. I was good at meditation. I started doing many, many hours a day. I told him I would like to become a nun. I went to Sri Lanka, and I was doing all-day meditation.

I lived in India doing meditation, going to see Sai Baba but as a Buddha. I was seeing him as a Buddha.

Very strange things happened to me when I was in Los Angeles. I came back to Los Angeles one time, because I was going and coming to India. I had a photo of Sai Baba. I was looking in his eyes. The separation was disappearing when I was looking in his eyes. I didn’t know if it’s me or him. There was no more separation.

I went back to India. There was a big conference about education. And he was with other people from the Ministry of Education, people from the government. He was in the middle of the table. And he started looking toward me. I was far from him, there were like twenty other people between us, but he was looking at me directly. He was not moving. I was also not moving. All the women in front of me separated. And I was just in front of him. We were looking into each other’s eyes, like I was back in my room in Los Angeles.

What was your Buddhist education like in Sri Lanka? My friend, Svetlana Darsalia, wanted to do a documentary of my work and my life and came with me to Sri Lanka. I wanted to meditate seriously, and she wanted to interview me, but I said, “Ah, enough of this Hollywood.”

Pemasiri Hamdruo, he was a really good teacher. Every afternoon he was giving teachings about the sutras. I was staying there in the monastery. It was a meditation center. He didn’t want anybody to stay long, so I had to go to India.

So I stayed in India. I loved India very much. I continued to do eight hours of meditation daily.

Later, in your artwork, at about the middle point of your career as a painter, you began to produce what you call the T-shape series, visualizing the contrast between life and death. These remind me of the reclining Buddha. Where did this creative inspiration come from? I was interested in the vertical and the horizontal from the beginning, because when I was doing the “White Period,” of my bed with white sheets, I was thinking these white sheets are very heavy and they are horizontal. And one day, figures started showing up from them and the horizontal line.

I know where I am when I paint. From the beginning, it was my teacher.

Everything was white. The white color that I was painting and the white wall behind the white sheets was the silence before painting. Much later, I discovered that Zen painters also have this white space. It has the meaning of the mind. It has to do with the mind that is silent. And from that whiteness comes everything.

I started to pay more and more attention to the whiteness, the vertical and the horizontal. But when the war started, I was more interested in what was going on in the street. I was painting many people in the streets, with empty spaces between them.

When I was doing the “White Period,” I was painting myself like an arrow going up. I said to myself, “I want to be an arrow, to go up all the time, like that, shooting up.” So I started painting people that were vertical.

But then, one day, I started painting people horizontally. Horizontality for me was the white sheet that was very heavy. In a way, it is about lightness and heaviness. These people were floating also. They were heavy but floating. I mean, it’s a paradox. It’s about people that can suddenly get angry and who are not thinking properly, then go here and there, like a leaf, not grounded. So this was the meaning of those paintings.

In Sri Lanka, while you were training to become a Buddhist nun, you stopped painting. Has there been a tension in your life since then, between artistic creativity and Buddhist practice? From time to time, I was rejecting painting and brushes and giving all my paintings to other people, as well as the canvases. And then I was returning to painting. It is like an addiction.

I know where I am when I paint. From the beginning, it was my teacher, in a way. What I’m doing now is mountains.

It has now been two years doing these mountains. They are like pyramids and churches and mosques, they have this form, right? And when you see them in person, it has this form that goes like a triangle, right? It points up. Again, it’s the vertical. So I’m doing this, mountains with a white background.

You have said that art has concepts and clings to beauty, whereas meditation has no concepts and searches only for truth, without clinging. Do you stand by this? Yes, I am wondering if I go on like this, in Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism, if I’m gonna be able to paint at the end. I wonder if it will not make any sense at the end. I am not there yet. To paint, I wonder if only the white is going to remain. Or not. Wow. But I’m not there.

Is there a connection between your experience of war and conflict and your search for peace, as opposed to the search for truth? If meditation is about truth-seeking, do you also come to the idea of peace? Is that important to your Buddhist practice? Well, Buddhism is about compassion and wisdom, right? So compassion comes because you are listening. I am still listening. I have always been listening to the news, and, also, I live in Hollywood. I am surrounded by homelessness. It is very painful, but like during the war in Lebanon, there is joy that doesn’t leave me.

I am wondering if I go on like this, in Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhism, if I’m gonna be able to paint at the end.

I have a vow to not say too much. But I can give a hint that compassion and wisdom go together. We are not affected to the point of being depressed or anything like that. My sangha and I are calm and happy inside, but at the same time, terribly moved by what is happening. Again, it’s a paradox, right?

Were you part of the selection process for your paintings as exhibited under Lebanese curator Christine Tohmé at the 18th Istanbul Biennial? In general, people like the work, the paintings of any artist that correspond to where they are at a certain moment in time, their perception of reality. Many people like my work during the war period because there is a war going on now. Must be that. I was doing this work when I was in Lebanon; some people loved them, some people really rejected them, very strongly. They want me to go back to the white bed sheets that I was doing.

I don’t pay attention to which period of my work people like because I accept that and understand that there is a war going on, so they are going to like my work during the war period.

Maybe later, when they want to get out of their depression or anxiety, they will start liking the work that I am doing now.

Can you explain to me the meaning of your Buddhist name, Ani Padma Tsul T’hrim Drolma? Tsul T’hrim means ethical discipline or moral discipline. And Drolma is Mother Tara, Red Tara.

Yes, my teacher Venerable Lama Chödak Gyatso Nubpa Rinpoche gave me that name. Everybody in my sangha is called Ani (Tib.: nun).

I have so many names. When I was in Sri Lanka, I was already given the name Mother Seta. And when I paint, I am Seta Manoukian. So many names. It’s like not having a name at all.

When you were in meditation training, did you confront historical trauma, perhaps thinking about your grandfather’s experience aiding victims, fellow Armenians, refugees from Turkey, during the Armenian genocide? No. But it was very much in my family, the sadness about the genocide but not the hatred. My family didn’t have any hatred toward Turkey at all. They were people incapable of hatred. They were extremely nice. And they didn’t hurt anybody.

My father, when people were cheating him out of his money or something, he would say, “Ah, maybe he needs it.” So they were not capable of hatred.

Can you explain the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism and what it means for you to be a practitioner of this path? The Nyingma tradition is when Padmasambhava came to Tibet from India. He was born in the Swat Valley. And there was a king that became Buddhist, Trisong Detsen, and he started the Nyingma tradition. It is the most ancient Tibetan Buddhist tradition. And then, later, other schools of Buddhism came.

To conclude, if I were to ask, what is important for you to say, finally, about your practice in Buddhism with respect to your life as an artist? In the Theravada tradition, we don’t have many visuals. We have the Buddha and the reclining Buddha, but Vajrayana tradition has so many visuals: flying dakinis, wrathful deities, and so much visual detail. It’s strange that my work doesn’t.

I look at the internet, and I see that artists are filling so much of their canvas. It’s so full and detailed. And mine are empty. Again, that white space.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.