On eight expeditions to Tibet between 1926 and 1948, Italian scholar and explorer Giuseppe Tucci (1894–1984) collected more than 200 portable paintings, or thangkas, from every part of the country and from every historical period between the 13th and 19th centuries. His collecting was informed by his background as a student of Eastern languages and religions, a growing familiarity with Tibetan culture, an interest in regional styles that were even then disappearing, and above all, a discerning eye and a taste for anomalous images.

Curated by the Asia Society’s Adriana Proser and guest curator Deborah Klimburg-Salter, professor emeritus for non-European art history at the University of Vienna, this exhibition brings together more than 50 of these works, all on loan from the Museum of Civilization-Museum of Oriental Art (MCMOA) in Rome. It not only presents a group of beautiful and unusual examples of Tibetan Buddhist art, but also a riveting account—told through archival photographs and a documentary film—of Tucci’s journeys.

The show opens with a spectacular 16th-century painting depicting a brilliant red Amitayus, one of the three long life deities in Tibetan Buddhism, ensconced in an edge-to-edge field of small copies of himself. Richly accoutered in rippling red, gold, and black robes and gold jewelry, Amitayus holds a bowl overflowing with the nectar of immortality, which spills into wine cups held by the 16th-century ruler King Jigten Wangchung, an important patron of the arts, and his son.

Related:Himalayan Buddhist Art 101: Calm Abiding

Tucci acquired this work, as he did every painting in these galleries, after it had been deemed too badly damaged—by water, by the soot and grease from offering lamps filled with animal fat, or simply by time—for use as a devotional object. In Tibetan Buddhism, such religious artifacts cannot be thrown away. Instead, they are stored or ceremonially buried; it is a testament to the trust that Tucci inspired in the lay and monastic communities he visited that he was allowed to buy or take them.

The painting and its companions owe their luminosity and legibility to a 30-year conservation effort mounted by the MCMOA, which still holds the bulk of Tucci’s collection. Still blurred, cracked, and faded in places, they brim with newly readable information. Rather than organize the works by style, religious tradition, or historical period, curator Klimburg-Salter has arranged them according to the two paths of Tibetan Buddhist devotional practice: the Sutrayana, in which enlightenment is achieved over many lifetimes and refuge is taken in the Buddha, dharma (teachings), and sangha (community), and the Vajrayana, or quick path, in which enlightenment can be reached in one lifetime through reliance on a lama, or guru; a yidam, or personal meditation deity; and beings known as protectors, who guard the dharma and the practitioner.

These images of the Buddhist cosmos and the activities of its saints, teachers, and deities tend toward great explicitness. In the section devoted to the Buddha, for instance, a 15th-century image of Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha, in the bhadrakalpa—an age in which there are 1,000 buddhas—portrays in minute detail a harmonious realm filled with enlightened beings and their devotees. Executed in deep burgundy, dark green, white, and now-faded gold, the painting shows a Buddha in meditation surrounded by a stepped display of nine more buddhas and eight stupas, or dome structures on a shrine. This grouping appears to be emanating from a low-lying puja table, which is used in devotional practices, covered with offerings and presided over by a lama, while the whole scene floats in a shimmering field of miniature repetitions of the main figure.

The painting is significant artistically as well as historically; it originated from Tholing, in Western Tibet, and its style and iconography are nearly identical to wall murals found in Tholing’s monasteries. In the course of restoring the thangka, an inscription was found hidden under its silk frame that mentions this particular artistic school as well as the name of the piece’s maker. While the lay and monastic creators of religious art in Tibet almost always worked anonymously, this inscription suggests that this artist, at least, took pride in his, and his compatriots’, work.

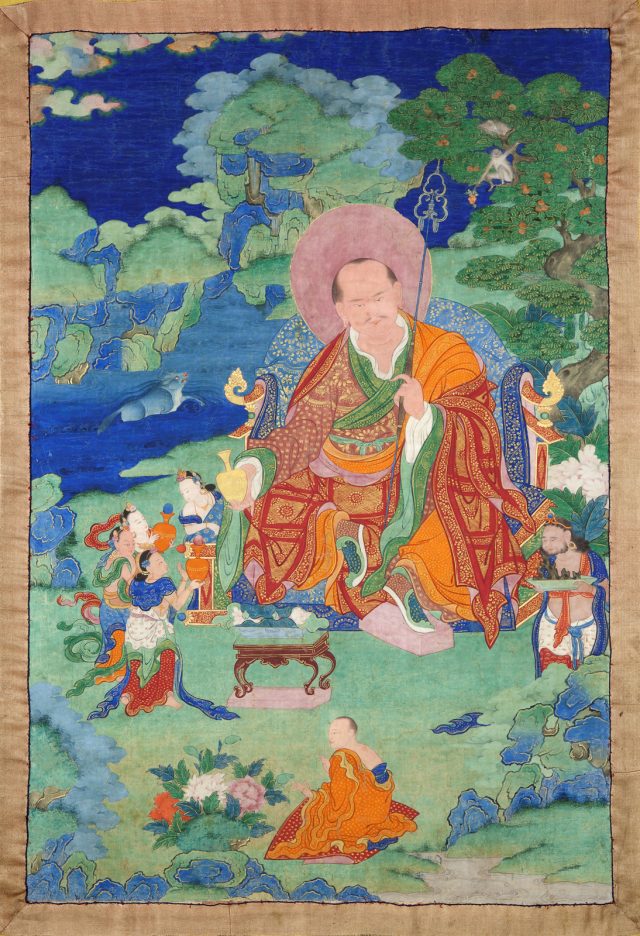

The sangha is represented in the show by an incomplete set of paintings from the 17th century of the 16 arhats, the Buddha’s original followers. The set was clearly produced by a number of artists, who, while following a basic color scheme and layout, each had a recognizably individual style. The impression is that of a fully realized world but viewed from slightly different perspectives. The individuality of the pieces is underscored by their careful notation of the arhats’ various attributes and quirks, including Abheda’s gem-spitting mongoose, Panthaka’s elephant, Ajita’s boldly patterned cloak, and Vanavasin’s slippers, which he has removed and hidden under his throne.

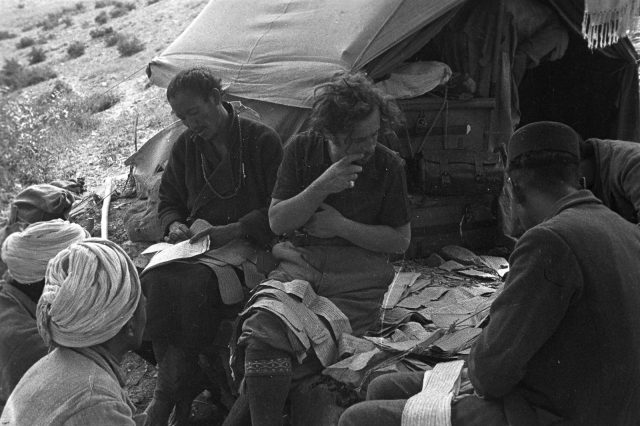

Three photographs of Tucci inspecting a trove of illustrated manuscripts—found buried in a cave high above Tholing Monastery by expedition photographer Eugenio Ghersi—stand in for the dharma in this exhibition. When Tucci arrived in Tibet nearly 100 years ago, he found a way of life already in danger of disappearing as a result of climate change and war. His extensive photographic record of Tibet’s artifacts, monuments, and people is in some cases the only surviving documentation of a cultural patrimony destroyed following the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1950.

(The exhibition press materials fail to mention that from the 1920s until the dictator’s death, Tucci was a supporter of Benito Mussolini and used idealizing interpretations of Asian traditions to promote Fascist agendas. The collection, however, stands on its own.)

In the sections devoted to tantric practice, the lamas include Padmasambhava, the towering Tibetan figure said to have brought tantra to Tibet. He features in several paintings; a wonderful thangka from the 1800s shows him appearing several times in the same bucolic landscape, each time in the guise of a different wrathful deity. This work is joined by a rare and beautiful 18th-century Bhutanese lineage tree with its progression of historical masters—one of a number of paintings emphasizing the importance of transmitted knowledge in Tibet’s oral traditions—and a depiction from the 16th or 17th century of four teachers, each with a student. Around them, tiny mahasiddhas, or tantric practitioners, giddily levitate, dance with dakinis, fly through space, and otherwise enjoy the magical fruits of their attainment.

The yidams include Green Tara, a popular Tibetan deity. In a thangka from the 1500s, she is surrounded by eight more Green Taras addressing eight perils, including water, imprisonment, and robbers—real dangers that travelers of the time would have encountered, but also metaphors for obstacles encountered on the path to enlightenment. Elsewhere are several beautiful mandalas, aids to navigating the realms of specific deities, and a wonderful 15-century painting of Dorje Jigje, a wrathful, buffalo-headed manifestation of Manjushri, the bodhisattva of wisdom. With his eight right feet, he tramples demons, and with his left he crushes eight kinds of birds. One of them, a goose, can be seen reaching its neck around to nip at his big toe, exacting a small but no doubt painful revenge.

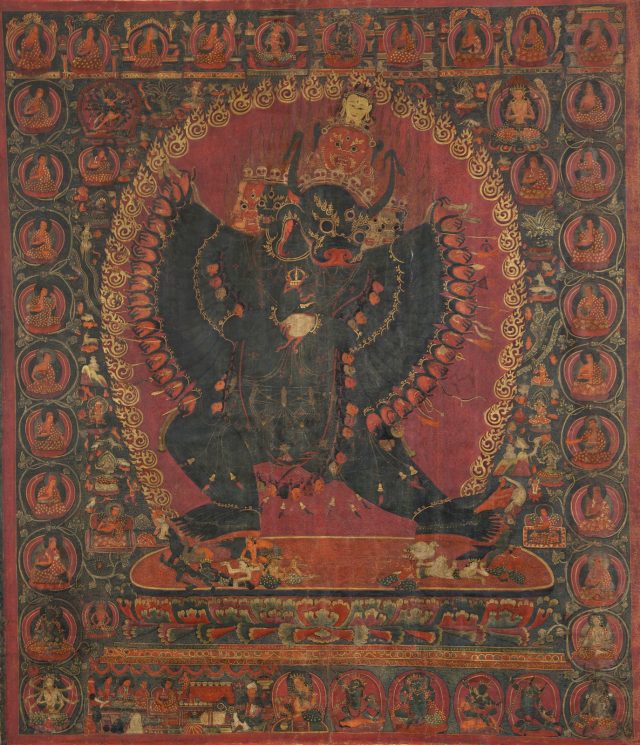

Sequestered in a separate gallery, the works in the show’s final, and most exciting, section depict the protectors of the dharma. These ravishing paintings, each a masterpiece, would make a knockout exhibition by themselves, and in a way, they do: they are separated from the rest of the show as they would have been separated from less esoteric images in a Tibetan temple. A 14th-century green-faced Vaisravana, the chief of the Four Heavenly Kings, in pale blue, wine, and lavender military garb and smart white boots sits flanked by eight representations of gardens, each occupied by a beautifully rendered cow. Garuda, a deity imported from pre-Buddhist Tibetan religions, appears twice: once in a finely detailed black and gold rendering from the 1700s, and once in a more folkish painting, made 200 years earlier, that emphasizes his stocky body, wild hair, and puffy feathered thighs. The final work is an 18th-century image of the Protectoress of Tibet, Palden Lhamo, who rides a prancing mule through clouds of smoke and fire.

Though extraordinarily varied, the artworks in this show are united by the vividness of the worlds and presences they depict. Their believability, paradoxically, underscores the possibility that our own world, so real to us, is itself only an illusion.

Unknown Tibet is on view at the Asia Society in New York City through May 20.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.