For Celts living 2,000 years ago, the days between the end of the summer harvest and the beginning of a cold, dark, and often-deadly winter were a time when the boundaries between worlds thinned, allowing hostile spirits to slip through and wreak havoc upon the living. To placate the dead, Celtic priests built sacrificial fires and wore costumes made from animal heads and hides as part of the festival of Samhain, which eventually evolved into Halloween. Although this holiday is now more associated with trick-or-treating and jack-o’-lanterns, even skeptics will admit that part of its lore still rings true. We all have experienced moments when the darker parts of our emotional and spiritual life bleed into the everyday.

Buddhist mythology emerged independently of Samhain and Halloween but it reflects the same impulse to tame the threatening aspects of our experience. In Buddhist folklore, supernatural beings are believed to haunt forests, mountains, cemeteries, and other liminal spaces between life and death. Our fear of the unknown is made manifest in these spirits who dwell in hallowed grounds, and our desire to channel their benevolent side is associated with Buddhist practices that can bring us closer to coexisting with the things that haunt us. Approaching images of protector deities from an art-historical perspective, as I do, can be a creative, intimate process that lends insight into their multifaceted nature and our own. Learning more about the role these unsettling figures play in Buddhist literature, art, and ritual practices can point to neglected aspects of our being. At the very least, this fearsome pantheon may rouse us into recognizing the macabre and insidious creatures lurking in our midst.

One of the most wild and dangerous of these beings is Parnashavari, a feared pisaci [class of wrathful spirit] in Nepalese and Indo-Tibetan Buddhism infamous for her ability to cause disease and incite conflict. Hailing from humble Indic folk origins, the “Leaf-Clad Mountain Woman” was absorbed by later Tibetan traditions into the Vajrayana pantheon, where she enjoys elevated spiritual status as a manifestation of the female bodhisattva Tara.

As with all wrathful deities, her powers go both ways—protection or destruction—which is why a substantial body of indigenous Tibetan literature is dedicated to ritual practices designed to invoke and propitiate her. Parnasavari’s dharani [short incantation] has circulated in India since as early as the 8th century, and it has remained an effective and popular rite of invocation for over a millennium. In light of the ongoing coronavirus, reciting her mantra has quite literally gone viral among today’s Tibetan Buddhist communities:

oṃ piśāci parṇaśavari sarvamāripraśamani svāha

Om hail to the pisaci Parnasavari who pacifies every pestilence!—Translated by Ryan Damron and Wiesiek Mical under the patronage and supervision of 84000: Translating the Words of the Buddha

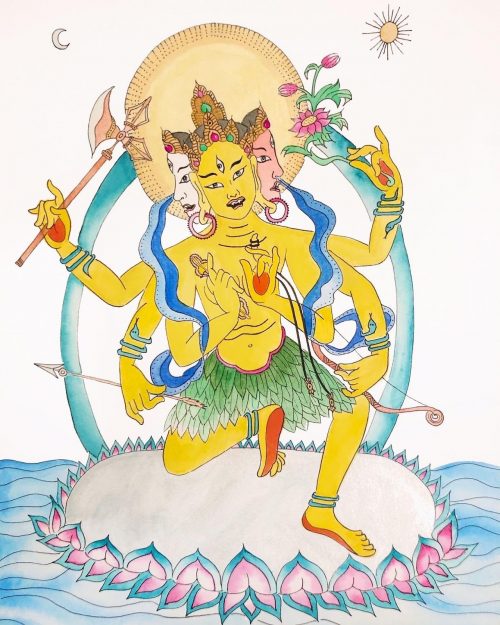

In Tibetan thangkas [scroll paintings], Parnasavari is often depicted as a three-faced yellow or green goddess who wields an axe, vajra, noose, bow, and arrow in her six arms. Her fangs, matted locks, tiger-skin sash, and skirt of thatched leaves represent her ferocious aspects and strong affinities with untamed spaces. Meditating on images of the pisaci is conceived as an effective way to enlist her assistance to deal with personal fears, anxieties, illnesses, and social or environmental calamities.

Pisacis play a prominent role in other in-between spaces, especially in the bardo, the “intermediate state” between death and rebirth. A vivid scene from a 19th-century painting of 8th-century tantric master Padmasambhava shows a dying practitioner ejecting his consciousness from the crown of his head—in a practice of deliberate transference known as phowa—toward the heavenly western Pure Land. Emerging from blazing flames is an animal-headed pisaci (Tib. tramen).

The female bardo deity clothed in human entrails and tiger skin is there to escort the practitioner through the netherworld. Danger awaits those seeking rebirth in a higher realm, as the thangka suggests, and both human and divine support will be necessary for this, or any, transformative journey. Much like the old Celtic Samhain celebrations and contemporary Halloween rituals, visualizing or dressing up as the monsters you fear—embodiments of death, ghosts, and the supernatural—are ways of identifying with and confronting what scares us the most.

Another figure in the Hindu-Buddhist pantheon that plays on the connection between fear and protection is Chamunda, the fiercest of the sapta matrikas, or “seven mother goddesses.” Unlike their more ferocious counterparts in Indian literature, artistic representations of the seven matrikas generally tend to appear benign, unthreatening, and domesticated. Around the 8th century, Chamunda broke away from her retinue and began to be worshipped as an independent force, especially in Saivite and Sakti tantric cults. According to the early Hindu epic Devi Mahatmya, an important literary and iconographic source for Hindu-Buddhist deities, Chamunda was born on the battlefield, springing forth from the forehead of the great goddess Durga in order to decapitate the demon generals Chanda and Munda.

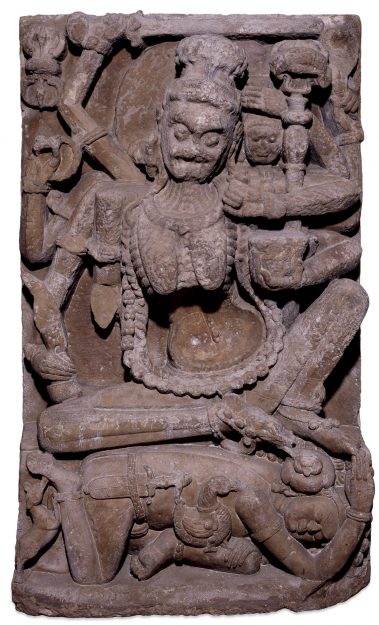

In sculpture, Chamunda is commonly represented in her emaciated skeletal form with a gaping mouth, sunken eyes, and pendulous breasts. Everything about her evokes destruction, death, and decay, particularly the corpse, ghost, or defeated warrior she crushes beneath her feet. Harvested from human bone, Chamunda’s jewelry attests to centuries of human and animal sacrifices that have been performed to satiate her bloodlust. It should therefore come as no surprise that temples dedicated to the unruly goddess across the Indian subcontinent have historically been situated on the outskirts of villages near charnel grounds.

Parnashavari, Chamunda, and other volatile beings in the Buddhist cosmos are powerful forces to be reckoned with. They thrive in the twilight spaces of earthly caches and in the deepest recesses of our minds. Practicing with these deities by invoking their mantras or engaging with their images not only help us to remain on their good side but also motivate us to probe the unsightly corners of our psyches without becoming unhinged.

For those artistically inclined, learning how to illustrate resonant wrathful deities can be an enriching way to become familiar with their iconography, history, and symbolism. While vengeful spirits can cause harm or leave us vulnerable to dangers unknown, take comfort in knowing that their poison can also double as a cure. Here are a few of my own illustrations of Parnashavari and Mahakala, which I hope inspire you to summon their power with your mind and brush.

♦

For more ideas on how (and where) to begin a Buddhist art practice, check out the following resources:

And if you’re interested in learning more about how sacred images work in Buddhism, see The Art of Awakening: A User’s Guide to Tibetan Buddhist Art and Practice by Konchog Lhadrepa and Charlotte Davis and Imaging Wisdom: Seeing and Knowing in the Art of Indian Buddhism by Jacob Kinnard. For further inspiration (and a creative outlet), follow the work of former monk and Tibetan calligrapher Tashi Mannox (@tashimannox), or sign up for an online Tibetan painting class with Sonam Rinzin of the Brooklyn Thangka Arts Studio or The School for Tibetan Art.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.