If someone asks you, “What is Zen?” you might want to share some teachings you’ve heard, or talk about the history of Buddhism, or tell them something about your practice. Or you can say, simply, “Zen cannot be explained.”

Chan (Jp: Zen) master Yaoshan Weiyan (745-828 CE) was asked to give a lecture at his monastery. He walked to the large chair at the front of the hall where he would sit when giving Dharma talks, and then, without saying a word, he turned around and went straight to his room. Later, his attendant asked him, “Why didn’t you speak?” and Yaoshan replied, “There’s no need to say anything.” Then he added, “If you want to study intellectually, you can go to a philosopher. I don’t need to speak. I just practice with you.” That statement conveys the spirit of thousands of Zen masters who have dedicated their lives to their students and the practice.

Answering “What is Zen?” is like answering “What is the ocean?” To understand the ocean, you have to submerge yourself. You have to get wet. You can dive into the first wave or bend your knees and let the wave wash over you, or if your timing is right, you can walk in without being knocked over. But it’s only after immersing yourself and engaging with water that you know what it means to be wet. If you stand at the water’s edge and dip your toe in, you won’t know the ocean. In Zen, we listen with our whole body, with our hopes, and with an empty mind, without trying to comprehend what it is intellectually, and without making a big deal of what we are doing. The only way is immersion.

There are thousands of academic studies on Zen, so many we probably won’t be able to read them all. Some are thoughtful, some profound, and some share stories from deep within the history of Buddhism. Studying these can help us understand the mind, the feelings, and the world views of Buddhists and scholars over the centuries. Explanations and studies can open the door and give us a glimpse, but we can’t understand the practice with just our intellect. As a subject of study, Zen can be something we can talk or write about. But ultimately we can’t really talk about it. We can only experience it viscerally, in an intuitive, feeling way. We understand practice in our gut, not in our head.

Here is a koan from the Blue Cliff Record. Koans are stories that can bring us to the limits of logic, intended to provoke a deeper understanding. The fourth patriarch of Chan, Daoxin (580-651 CE) had three attendants, Guishan, Yunju, and Go-on. Daoxin asked Guishan, “With mouth and lips closed, how would you say it?” Guishan replied, “I would ask you to say it!” Daoxin told him, “I could, but if I did, I’d have no successors.”

The Fourth Patriarch’s question means: How do you express truth in everyday actions? His disciple, Guishan, says he can respond only if he doesn’t use his intellect. Daoxin replies that if Guishan were to speak, he (Master Daoxin) wouldn’t have any successors, affirming his student’s response by saying that he doesn’t rely on intellect either. Zen practice, and life, have to be understood through experience—like going in the ocean. To understand Zen practice, and our life, we need confidence and dedication. When we’re confused, which is a lot of the time, we have to work to unravel the confusion. We keep practicing; time is not a consideration. “Practice without end” is our attitude, and it’s this kind of confidence that awakens insight.

Here is a story from medieval Japan. In the fourteenth or fifteenth century, a man who wanted to master sword fighting, Kendo, went to study with the most famous swordsman of the day. The student asked, “How long will it take for me to master your way?” and the teacher replied, “If you want to master Kendo in three years, it will take a century. But if you don’t worry about anything, even that you might be killed by your teacher, you’ll master it immediately.” Immediacy is the way. We must be ready to enter the great unknown.

Zen practice, and life, have to be understood through experience—like going in the ocean.

When we understand the importance of practice to our life, we’ll have strong determination and we’ll remind ourselves, “I will sit in meditation without moving. I’ll move only when the doan rings the bell.” Our practice is not for comfort or convenience; it’s to encourage determination. And we make the effort to extend this attitude to everything we do. Of course, our determination can get short-circuited by desires and thoughts. So, we have to keep coming back to our zafu (meditation cushion) and renew our determination.

When we receive a gift from a friend, we don’t say, “Actually, I wanted something else.” We accept the gift without judgment. If we realize we wanted something else, we have to let that feeling go, come back to the mind of zazen, which is empty of desires, so that we can express our appreciation. Our attitude is accepting, and we emphasize serving others, not just ourselves and what we want. This is the way of the bodhisattva, literally an “awakening being.”

Imagine if someone unborn were to arrive and ask, “What is life? What is your life?” You could give them a long answer about various aspects of living, but the being from another dimension wouldn’t understand. The best you can offer is to help them come alive. You don’t need to say anything. When we meet people like this, we can try to help them come alive. The best Zen teachers always taught this way. They don’t explain; they simply invite you to practice. The invitation might even be given in silence.

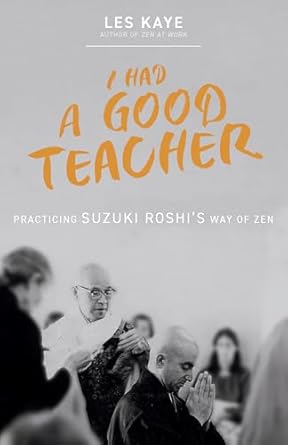

Suzuki Roshi gave many lectures to explain the teachings of Zen. Doing so was necessary for us, we were all new to the practice. But his greatest gifts were offered nonverbally. His way wasn’t dramatic like the old masters. He was very quiet. What impressed me most was his continuous practice. He created opportunities so others could join him, and then he let us find our own way, gently, without trying to control and without scolding us. He let us make mistakes, try again, and learn. When we see that we’re holding back from life, we don’t need our teacher to scold us. We simply renew our determination to enter the water and get wet.

♦

From I Had a Good Teacher: Practicing Suzuki Roshi’s Way of Zen © 2025 by Les Kaye. Reprinted with permission from Monkfish Book Publishing Company.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.