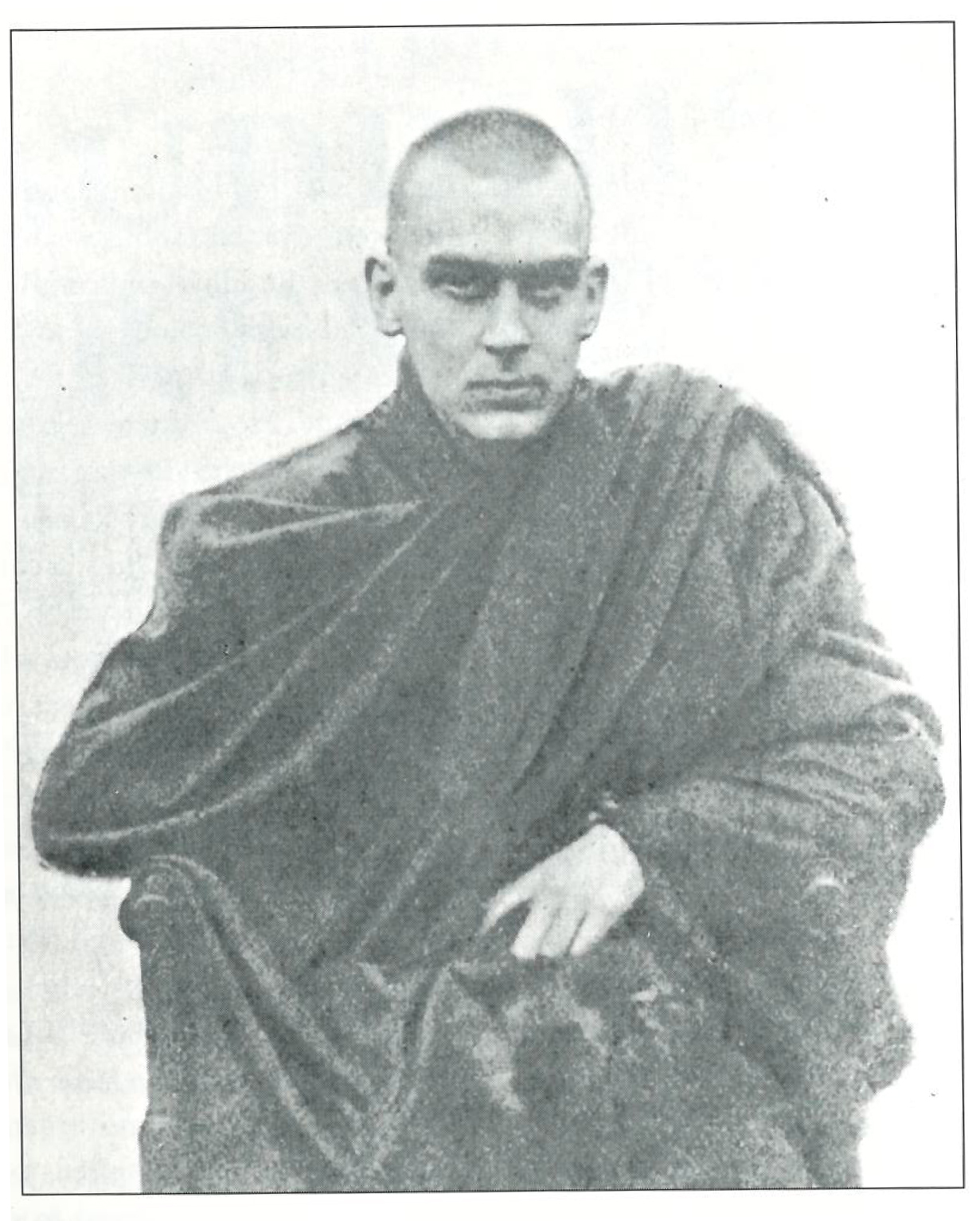

In 1908, Allan Bennett, a British subject sailing from Burma, docked in London intending to found the first Theravada Buddhist monastic community in the West. His community never flourished, but Bennett, the second-ever British subject to be ordained a Theravada bhikkhu, made his mark on the religious landscape of England: he started a Buddhist mission, a journal—The Buddhist Review—and planted the seeds for sanghas that blossomed decades after his death in 1923.

Bennett was born in 1872 and by age eighteen was calling himself a Buddhist. His initiation to the dharma was the nineteenth-century volume The Light of Asia, by Sir Edwin Arnold. He then joined the Order of the Golden Dawn, an organization of occultists that attracted British intellectuals with a taste for Eastern spirituality. As a young man, Bennett trained as an “analytical chemist” and he had emerged as an innovator in the budding field of electricity when chronic asthma cut his career short. On medical advice, he decided go “out East”—it seemed to him the perfect solution for physical and spiritual therapy.

In 1900, Bennett arrived in Ceylon, where he began to study Pali and Buddhism. After six months, one of his contemporaries wrote, he could “converse fluently in that sacred tongue” and by the next year was giving talks on dharma at the Theosophical Society’s Hope Lodge in Colombo. By 1901, Bennett had made up his mind to take monastic vows. He traveled to Burma to “renounce the world” as a samanera, or novice, and took the name Ananda Metteyya. He studied in Burma for a year before receiving a higher ordination of upasampada, by which time plans for teaching the dharma to Westerners were already germinating in Bennett’s mind: after his second ordination, with the help of a Burmese Buddhist philanthropist, he inaugurated the Buddhasasana Samagam, or International Buddhist Society, along with an illustrated quarterly magazine called Buddhism, which he edited.

In Rangoon, Bennett declared he would “carry to the lands of the West the Law of Love and Truth declared by our master, to establish in those countries the Sangha of his priests.” And so, in 1908, he set sail for his homeland to fulfill his mission. Bennett exuded nobility and was extremely well versed in Buddhist philosophy, and his arrival was heralded by the country’s small cluster of Buddhists as an auspicious start to the spreading of dharma in Europe. He immediately founded the Buddhist Society of Great Britain and Ireland and began printing The Buddhist Review, which he edited and wrote articles for. But according to the scanty accounts of the organization’s early days, his work in London, while groundbreaking, wasn’t a great success. Bennett wasn’t a compelling public speaker, his asthma grew worse, and just six months after establishing the Buddhist Society, he abandoned the new sangha and returned to Burma.

Six years later, Bennett had become a thera, or elder, in his Burmese order. But his health had deteriorated to the point where he was forced to disrobe and return to England once again, on the eve of World War I. Too ill to travel on to California, where he’d planned to convalesce, Bennett stayed in London and helped revitalize his mission, which was floundering in the chaotic atmosphere of the war. Bennett also relaunchedThe Buddhist Review and edited it until his death in 1923, at the age of fifty. His Ceylonese colleagues eulogized him in a 1923 essay in The Buddhist, a journal published in Colombo: “His broken body could no longer keep pace with his soaring mind. The work he began, that of introducing Buddhism to the West, he pushed with enthusiastic vigor in pamphlet, journal and letter, all masterly, all stimulating thought, all in his own inimitably graceful style. And the results are not disappointing, to those who know.”

If we [Western practitioners] be indeed worthy of the name of Followers of the Buddha, it behooves us, first and foremost, to understand the full meaning that that title has for us; and, not less essentially, to consider what course of action we must follow, if we are to make the most of the great opportunity that our Karma now has brought to us.

All that remains to us is Action—not the vain claim that we are Followers of the Buddha, whilst yet our lives are empty of the pity and the love and the helpfulness He taught, but action true, following to the best of our small powers; it is not vain talk and futile declamation, nor even, by itself, mere learning in the ancient Texts, that make a man our Master’s Follower—but love for all, but work, but life.

So let whoso shall make that claim content himself with that—your privilege it is to do the work, to help the spreading of the Law of Love; to live according to the Buddha’s message. Suffer no attack, and no futility, to alter in the least your contribution to the welfare of Humanity, remembering that the world can only judge Buddhism by your actions, by your love, your life. So may you help to render to the Western World that greatest of all services whereof it stands so sorely now in need: the spreading of the great Religion which, from the small beginning now made, will yet grow till all the thinking West stands where you stand today; and which in very fact is the sole cure for all its manifold sufferings—sole cure for its deep-rooted self-idolatry which, as Arnold has so accurately put it, “Crying ‘I,’ I would have the world say “I.'”

And so, remembering in daily practice of Right Mindfulness, who and what you are—what your high privilege, and what your Hope in life—bear ever in your hearts the last, great exhortation that the Master uttered, when, at the close of that long life which did so much to change the history of mankind, He passed away into that utter passing which leaves no remnant of the self behind it:

—“Lo! now, O brothers, I exhort ye! Decay is inherent in all the Tendencies—wherefore by earnestness work out your Liberation.”

—Ananda Metteyya (Allan Bennett)

London, the 15th Waning of Potthapada, 2,452

(September 24, 1908)

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.