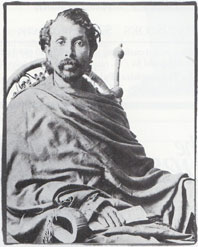

Born to a devout Buddhist family in 1864, David Hewivitarne became Anagarika Dharmapala, the leading light of the Buddhist Renaissance Movement in Sri Lanka. As a child, Dharmapala was sent to Christian missionary schools, where his education, if comprehensive by European standards, showed little respect for Buddhism. By the age of nineteen, he had mastered the rudiments of Christian theology and knew more than half the Bible by heart, knowledge he used to highlight the hypocrisy he perceived in his missionary instructors. When a mob of Sri Lankan Catholics attacked a Buddhist procession in 1883, Dharmapala left school and turned his intellectual pursuits to Buddhism instead. Soon afterwards Colonel Henry Steel Olcott and Madame Blavatsky, founders of the Theosophical Society in New York, arrived in Sri Lanka and filed suit on behalf of the Buddhists who were injured in the attack. Dharmapala, who felt that the Society’s aims were identical to those of a Buddhist revival in Sri Lanka, became a member. Madame Blavatsky took the young man under her tutelage, and he remained her loyal supporter for the rest of his life.

Following the Theosophical Society Convention of 1890 in Adyar, South India, Dharmapala traveled to Japan on behalf of the Society, and later returned to India, where he was to find Bodh-gaya, the site of the Buddha’s enlightenment, in a state of ruin. Resolved to restore Bodh-Gaya to its former status as a Buddhist holy site, Dharmapala began an international campaign that was to last until his death in 1933.

In 1893, Dharmapala was invited to Chicago to address the World Parliament of Religions. His address, along with that of Japanese Zen master Soyen Shaku, catalyzed the first wave of interest in Buddhism among European-Americans. The following portion of Dharmapala’s address is excerpted from The Dawn of Religious Pluralism: Voices from the World’s Parliament of Religions, 1893, edited by Richard Hughes Seager (Open Court Publishing Company, 1993). Dharmapala’s original spellings and usage have been preserved throughout the text.

The Dawn of a New Era

History is repeating itself. Twenty-five centuries ago India witnessed an intellectual and religious revolution which culminated in the overthrow of monotheism, priestly selfishness, and the establishment of a synthetic religion, a system of life and thought which was appropriately called Dhamma—Philosophical Religion. All that was good was collected from every source and embodied therein, and all that was bad discarded. The grand personality who promulgated the Synthetic Religion was known as BUDDHA. For forty years he lived a life of absolute purity, and taught a system of life and thought, practical, simple, yet philosophical, which makes man—the active, intelligent, compassionate, and unselfish man—to realize the fruits of holiness in this life on this earth. The dream of the visionary, the hope of the theologian, was brought into objective reality. Speculation in the domain of false philosophy and theology ceased, and active altruism reigned supreme.

Five hundred and forty-three years before the birth of Christ, the great being was born in the Royal Lumbini Gardens in the City of Kapila-vastu. His mother was Maya, the Queen of Raja Sudohodana of the Solar Race of India. The story of his conception and birth, and the details of his life up to the twenty-ninth year of his age, his great renunciation, his ascetic life, and his enlightenment under the great Bo tree at Buddha Jaya, in Middle India, are embodied in that incomparable epic,“The Light of Asia,”by Sir Edwin Arnold. I recommend that beautiful poem to all who appreciate a life of holiness and purity.

Six centuries before Jesus of Nazareth walked over the plains of Galilee preaching a life of holiness and purity, the Tathagata Buddha, the enlightened Messiah of the World, with his retinue of Arhats, or holy men, traversed the whole peninsula of India with the message of peace and holiness to the sin-burdened world. Heart-stirring were the words he spoke to the first five disciples at the Deer Park, the hermitage of Saints at Benares.

His First Message

“Open ye your ears, O Bhikshus, deliverance from death is found. I teach you, I preach the Law. If ye walk according to my teaching, ye shall be partakers in a short time of that for which sons of noble families leave their homes, and go to homelessness—the highest end of religious effort: ye shall even in this present life apprehend the truth itself and see it face to face.” And then the exalted Buddha spoke thus: “There are two extremes, O Bhikshus, which the truth-seeker ought not to follow: the one a life of sensualism, which is low, ignoble, vulgar, unworthy, and unprofitable; the other the pessimistic life of extreme asceticism, which is painful, unworthy, and unprofitable. There is a Middle Path, discovered by the Tathagata [Shakyamuni Buddha]—the Messiah—a path which opens the eyes and bestows understanding, which leads to peace of mind, to the higher wisdom, to full enlightenment, to eternal peace. This Middle Path, which the Tathagata has discovered, is the noble Eight-fold Path, viz.: Right Knowledge—the perception of the Law of Cause and Effect, Right Thinking, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Profession, Right Exertion, Right Mindfulness, Right Contemplation. This is the Middle Path which the Tathagata has discovered, and it is the path which opens the eyes, bestows understanding, which leads to peace of mind, to the higher wisdom, to perfect enlightenment, to eternal peace.”

Continuing his discourse, he said: “Birth is attended with pain, old age is painful, disease is painful, death is painful, association with the unpleasant is painful, separation from the pleasant is painful, the non-satisfaction of one’s desires is painful, in short, the coming into existence is painful. This is the Noble Truth of suffering. “Verily it is that clinging to life which causes the renewal of existence, accompanied by several delights, seeking satisfaction now here, now there—that is to say, the craving for the gratification of the passions, or the craving for a continuity of individual existences, or the craving for annihilation. This is the Noble Truth of the origin of suffering. And the Noble Truth of the cessation of suffering consists in the destruction of passions, the destruction of all desires, the laying aside of, the getting rid of, the being free from, the harboring no longer of this thirst. And the Noble Truth which points the way is the Noble Eight-fold Path.” This is the foundation of the Kingdom of Righteousness, and from that center at Benares, this message of peace and love was sent abroad to all humanity: “Go ye, O Bhikshus and wander forth for the gain of the many, in compassion for the world for the good, for the gain, for the welfare of gods and men. Proclaim, O Bhikshus, the doctrine glorious. Preach ye a life of holiness, perfect and pure. Go then through every country, convert those not converted. Go therefore, each one traveling alone filled with compassion. Go, rescue and receive. Proclaim that a blessed Buddha has appeared in the world, and that he is preaching the Law of Holiness.”

The essence of the vast teachings of the Buddha is:

The entire obliteration of all that is evil.

The perfect consummation of all that is good and pure.

The complete purification of the mind.

The wisdom of the ages embodied in the Three Pitakas—the Sutta, Vinaya, Abhidhamma, comprising 84,000 discourses, all delivered by Buddha during his ministry of forty-five years. To give an elaborate account of this great system within an hour is not in the power of man.

A systematic study of Buddha’s doctrine has not yet been made by the Western scholars, hence the conflicting opinions expressed by them at various times. The notion once held by the scholars that it is a system of materialism has been exploded, The Positivists of France found it a positivism; Buchner and his school of materialists thought it was a materialistic system; agnostics found in Buddha an agnostic, and Dr. Rhys Davids, the eminent Pali scholar, used to call him the “agnostic philosopher of India”; some scholars have found an expressed monotheism therein; Arthur Lillie, another student of Buddhism, thinks it a theistic system; pessimists identify it with Schopenhauer’s pessimism, the late Mr. Buckle identified it with [the] pantheism of Fichte; some have found in it a monism; and the latest dictum of Prof. Huxley is that it is an idealism supplying “the wanting half of Bishop Berkeley’s well-known idealist argument.”

In the religion of Buddha is found a comprehensive system of ethics, and a transcendental metaphysic embracing a sublime psychology. To the simple-minded it offers a code of morality, to the earnest student a system of pure thought. But the basic doctrine is the self-purification of man. Spiritual progress is impossible for him who does not lead a life of purity and compassion. The rays of the sunlight of truth enter the mind of him who is fearless to examine truth, who is free from prejudice, who is not tied by the sensual passions and who has reasoning faculties to think. One has to be an atheist in the sense employed by Max Muller: “There is an atheism which is unto death, there is another which is the very life-blood of all truth and faith. It is the power of giving up what, in our best, our most honest moments, we know to be no longer true; it is the readiness to replace the less perfect, however dear, however sacred it may have been to us, by the more perfect, however much it may be detested, as yet, by the world. It is the true self-surrender, the true self-sacrifice, the truest trust in truth, the truest faith. Without that atheism, no new religion, no reform, no reformation, no resuscitation would ever have been possible; without that atheism, no new life is possible for any of us.”

The strongest emphasis has been put by Buddha on the supreme importance of having an unprejudiced mind before we start on the road of investigation of truth. Prejudice, passion, fear of expression of one’s convictions, and ignorance are the four biases that have to be sacrificed at the threshold.

To be born as a human being is a glorious privilege. Man’s dignity consists in his capability to reason and think and to live up to the highest ideal of pure life, of calm thought, of wisdom without extraneous intervention. In the Saimanna phala Sutta Buddha says that man can enjoy in this life a glorious existence, a life of individual freedom, of fearlessness and compassionateness. This dignified ideal of manhood may be attained by the humblest, and this consummation raises him above wealth and royalty. “He that is compassionate and observes the law is my disciple,” says Buddha.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.