WHEN YOU think of the words “American Buddhist,” what do you see? Someone white, middle-aged, no kids? An adult convert from Protestantism? Someone with a graduate degree, living in the western United States?

WHEN YOU think of the words “American Buddhist,” what do you see? Someone white, middle-aged, no kids? An adult convert from Protestantism? Someone with a graduate degree, living in the western United States?

The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life’s “2008 U.S. Religious Landscape Survey,” released in late February, may provide some new clues about what American Buddhists are like. The Pew Forum conducted more than 35,000 telephone surveys with adult respondents, 0.7% of whom identified themselves as Buddhist.

A caveat: While the resulting figures are interesting and may be useful in evaluating American sangha development, care must be taken in relying heavily on them. The margin for error is +6.5%, and only 411 respondents identify themselves as Buddhist. Also, Hawaii, home to a significant number of Buddhists, was not included in the survey.

Nonetheless, larger trends and themes emerge and help to point out where further study is needed.

MORE than half (53%) of Buddhist respondents are white; another third (32%) are Asian or Asian-American. Nearly three-quarters of Buddhist respondents (74%) were born in the U.S. In addition, gender was equally represented: 53% of Buddhist respondents are male and 47% female.

Buddhists are among the most highly educated respondents, with nearly three-quarters (74%) having attended college. More than a quarter (26%) have graduate degrees, compared with 10% of the American population as a whole.

When it comes to income levels, Buddhist respondents cluster at both ends of the spectrum. A quarter make less than $30,000 a year, but almost as many (22%) earn more than $100,000 annually. More than half (56%) make more than $50,000 a year.

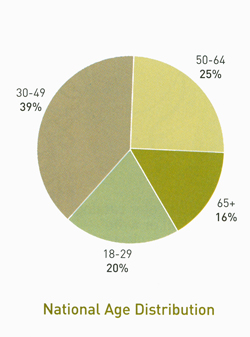

A plurality of Buddhist respondents (40%) are between 30 and 49 years of age, with another 30% being between 50 and 64. Less than a quarter (23%) are between 18 and 29 years old.

Almost three-quarters (73%) of Buddhist respondents converted to the practice; only 27% were raised Buddhist. Nearly a third of Buddhist respondents (32%) are former Protestants; another 22% are former Catholics, and 6% belong to other faiths, including Judaism.

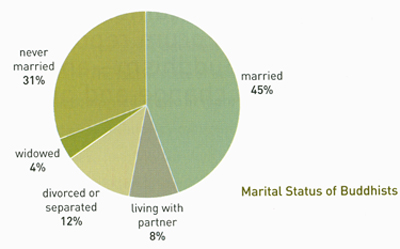

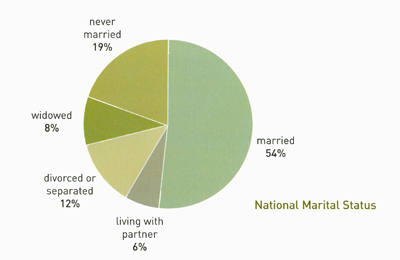

Under half (45%) of Buddhist respondents are married; another third (31%) have never married, and 12% are divorced. Of married Buddhist respondents, more than half (55%) have non-Buddhist spouses.

Most of these spouses (27%) are unaffiliated with any religion; 15% are Protestant. In the U.S. Population overall, 37% are married to a spouse with a different religious affiliation.

The vast majority (70%) of Buddhist respondents do not have children at home. Comparatively, the figure is 61% for Catholics, 66% for Protestants, and 72% for Jews. Of children raised Buddhist, half do not continue to practice when they reach adulthood, 28% percent stop practicing any religion, and 22% change to another faith. Buddhists and Jehovah’s Witnesses are the two religious groups showing the lowest retention rate.

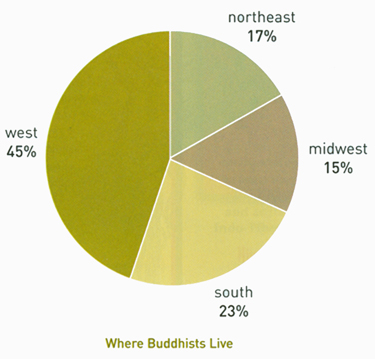

The largest group of Buddhist respondents (45%) live in the West; almost a quarter (23%) live in the South. California and New Mexico are the states claiming the largest number of respondents.

MORE than a quarter of Pew respondents (28%) report that they have left the religion in which they were raised. While every religious group is experiencing turnover, some are growing by gaining adherents faster than they are losing them.

The group of respondents who are unaffiliated with any particular religion (16.1%) is the fastest-growing segment, despite having one of the lowest retention rates of any group.

Looking at gender figures, 20% of men report no religious affiliation, compared with 13% of women.

The unaffiliated are relatively young: 31% percent are under age 30, and 71% are younger than 50. A quarter of young adults ages 18 to 29 say they are unaffiliated.

Christians make up the largest segment of the U.S. Population (78.4%), with Protestants making up slightly more than half (51.3%) and Catholics nearly another quarter (23.9%).

The findings raise some useful questions for the continuing development of the American Buddhist sangha. For instance, constructing and conducting a Buddhist practice together as a family appears not to be a central concern for the majority of respondents. Most married Buddhist respondents have nonpracticing spouses and are not raising children, and most Buddhist children have given up the practice by the time they grow up. In addition, the 18-to-29 age group is one of the smallest among Buddhist respondents, second only to the 65+ group (7%). What does the low number of young practitioners mean for the future of American Buddhism? Clearly the largest influx of new practitioners is coming from adults who convert. Adult religious education will likely continue to be a focus of American sanghas, given that most new practitioners have grown up in another tradition (or no tradition) and there is little underlying cultural understanding of Buddhism. What do new practitioners bring with them from their previous traditions, and what do they need to know in order to effectively begin and maintain their Buddhist practice?

With nearly three-quarters of Buddhist respondents having some college education, and more than a quarter with graduate degrees, it would seem that colleges and surrounding areas present fertile ground for the spread of the dharma. Are there also opportunities for sanghas to reach out to potential practitioners whose educational path does not include college? How might this be done? And what about non-white, non-Asian practitioners? Only 6% of Buddhist respondents were Latino, 4% black, and 5% mixed race or other. According to U.S. Census figures, 15% of the U.S. Population identifies as Latino, while 13% identify as black. Perhaps there are opportunities for growing sanghas to reach out to and provide meaningful practice experience for underrepresented groups in their areas.

Finally, the widely divergent income levels of Buddhist respondents are worth considering in planning for sangha development. The need to gather financial support is a source of discomfort in some sanghas, raising questions about clinging, greed, and acceptance. These are certainly issues that need examination within the context of Buddhist teaching. However, a perceived sense of lack may not actually reflect the sangha’s circumstances. Granted that income levels will vary by geography, if 39% of American Buddhists are earning more than $75,000 annually and more than a fifth (22%) earn more than $100,000, there are likely some very meaningful giving opportunities available that would benefit both the donor and the sangha. How can sanghas create a healthy climate of giving that encourages those with the financial means to help support practice? On a related note, if the quarter of Buddhist respondents making less than $30,000 a year are suffering because of their income level, can sanghas offer help through workstudy programs, discounted program fees, or other initiatives? Are there other basic needs with which the practice community can help?

More recently, the Pew Forum released the second half of the survey, which explores the social and political views of respondents along with the specifics of their religious beliefs and practices. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Buddhists were the most liberal of any religious affiliation surveyed. 50% of Buddhists identified as liberal, while just 12% identified as conservative, leaving 32% as moderates. Nationwide, 20% of respondents are liberal, 37% are conservative, and 36% are moderate. Buddhists were also more likely than any other single faith to be accepting of homosexuality:82% of respondents stated that they believed that homosexuality should be accepted by society, as compared to 50% of respondents nationally. 81% of Buddhists surveyed said that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, as opposed to a national average of 51%. Collectively, these results suggest that many Buddhists lean leftward on today’s most debated social issues—finding themselves at odds with about half of the country.

However, many Buddhists do share the greater number of American’s belief in God or a universal spirit: 39% stated that they were certain of a higher power, while 28% ranked themselves as fairly certain. Nationwide, those numbers are 71% and 17%, respectively. 19% of Buddhists said that they did not believe in God, while only 5% of nationwide respondents said the same. What does all of this tell us about how Buddhism in America may evolve down the road? While it’s inadvisable to generalize, it’s safe bet that it will be driving a Prius.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.