It was November 3, 2001, the day before the long-awaited mass conversion. Ram Raj had been expecting one million to attend. Agitated, he appeared at my hotel soon after I arrived in Delhi: “Quickly, we have little time,” he shouted, and six of us crammed into a car. Raj barked into his cell phone as we weaved through the crazy Delhi traffic. This was a crisis.

“I’m underground. This morning the government banned the conversion, and they want to arrest me,” Raj explained. “They say so many people converting will threaten public order. So they’ve barricaded the venue and are turning people back.” The car arrived at Raj’s headquarters where he gave an impromptu press conference. “This affronts freedom of religion. The Hindus are afraid. Their time is ending!” Welcome to Buddhism, North Indian style.

Raj is a dalit, one of 150 million considered “untouchable” under the Hindu caste system. For millennia dalits have been the lowest of India’s low. Untouchability was abolished in 1950 under India’s constitution, but the dalit’s position is like that of American blacks following the abolition of slavery. Prejudice, even atrocities, are common, and, in the case of the caste system, such behavior has a religious sanction. Though the world has ignored it, some consider caste an iniquity worse than apartheid, and one affecting far more people. Hinduism offers dalits nothing, and thus many of them are turning to Buddhism.

The key figure behind these events is Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, the statesman and dalit leader who still dominates the community’s consciousness forty-five years after his death. He represented dalits in independence negotiations and framed India’s constitution, which outlawed untouchability. Ambedkar knew that legislation was not enough and that a religious solution was required. For years he worked to reform Hinduism. Gandhi proposed that the caste system should remain, but that Hindus should act better toward the lower castes. Ambedkar, however, concluded that caste and Hinduism were inseparable and that the dalits must help themselves. In 1956, at a vast public ceremony in Nagpur, Ambedkar took the Refuges and precepts, and then initiated 500,000 others into Buddhism. Millions more followed them in the subsequent months.

Ambedkar was far more than a politician. In the hutments and shantytowns of his native Maharashtra, his picture sits on a million shrines alongside the Buddha, representing dalit dignity, hope, and freedom. Ambedkar told his followers that Buddhism offered a new birth, but they must practice its teaching to fulfill its promise. So alongside social aspirations, many of that first generation of converts wanted deeply to understand their new faith. But Ambedkar died a several weeks after converting, and only a few individuals (notably the English Buddhist Sangharakshita) kept the flame alive. Although Ambedkar’s movement has been riven by factionalism, some few have found ways to practice Buddhism effectively.

Forty-seven-year-old Ram Raj entered the scene as a leader of the new dalit middle class, three million dalit government employees who’ve benefited from affirmative action provisions. Within India’s present government, the Hindu nationalist party, the BJP, with its fundamentalist elements, threatens to roll this program back; desperate to protect the dalits’ slender hold on social advancement, Raj’s organization has opposed the government with increasing fervor. Following Ambedkar’s example, and perhaps seeking to don his mantle, Raj announced last year that he would convert to Buddhism. Dalits and other low-caste communities, faced by resurgent Hindu supremacism, have been stirred, and millions are reportedly planning to convert across the country. Raj himself believes that tens, perhaps hundreds of millions will become Buddhists, while Christian groups hope to win these converts for themselves

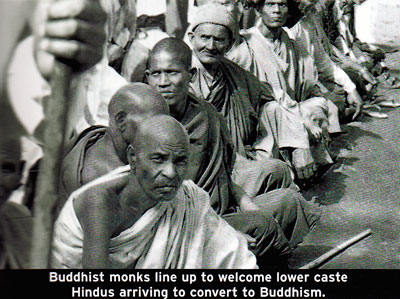

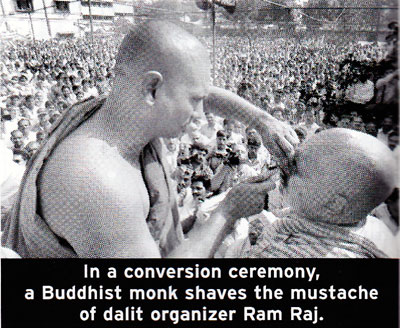

When the day came, close to ten thousand followers packed Ambedkar Bhavan, the emergency venue, and many others were doubtless turned away or put off by the announced cancellation. Raj, dressed in layman white, stood surrounded by dalit bhikkhus. After he recited the Three Refuges and the precepts, Buddha Priya Rahul, the presiding monk, gave him a new name – Udit, “having risen.”

The atmosphere was two parts political to one part religious, but in India, religion and politics are inseparable. Religion is identity, and in becoming Buddhists the dalits claim the right to define themselves. “What was Dr. Ambedkar’s last wish?” went the chant. “That we adopt Buddhism,” came the reply. People punched the air as speakers criticized the BJP and dalit leaders who opposed the event.

Ambedkar told his followers that if they were Buddhists in name only little would change. Raj advocates conversion, but there is scarce indication that he has fully considered what it means to follow Buddhism. Many Ambedkarite Buddhists are wary of him, but he is charismatic, focused, and making waves. And if nothing else, the conversions may sow seeds for a genuine encounter with Buddhism.

The crowd, joined by newcomers, marched to Ramlila Ground, the original venue, where they encountered barricades and a phalanx of riot police. The crowd turned their back on the police, and Buddha Priya led a second conversion ceremony from the roof of a neighboring building. It was an apt symbol of the struggle of the dalits, excluded for so long from Hindu society, to be their own masters. Ambedkar’s “peaceful Dhamma revolution” is on the march again, but India today is a deeply polarized society and no one can predict the consequences if the Hindu order is truly threatened. ▼

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.