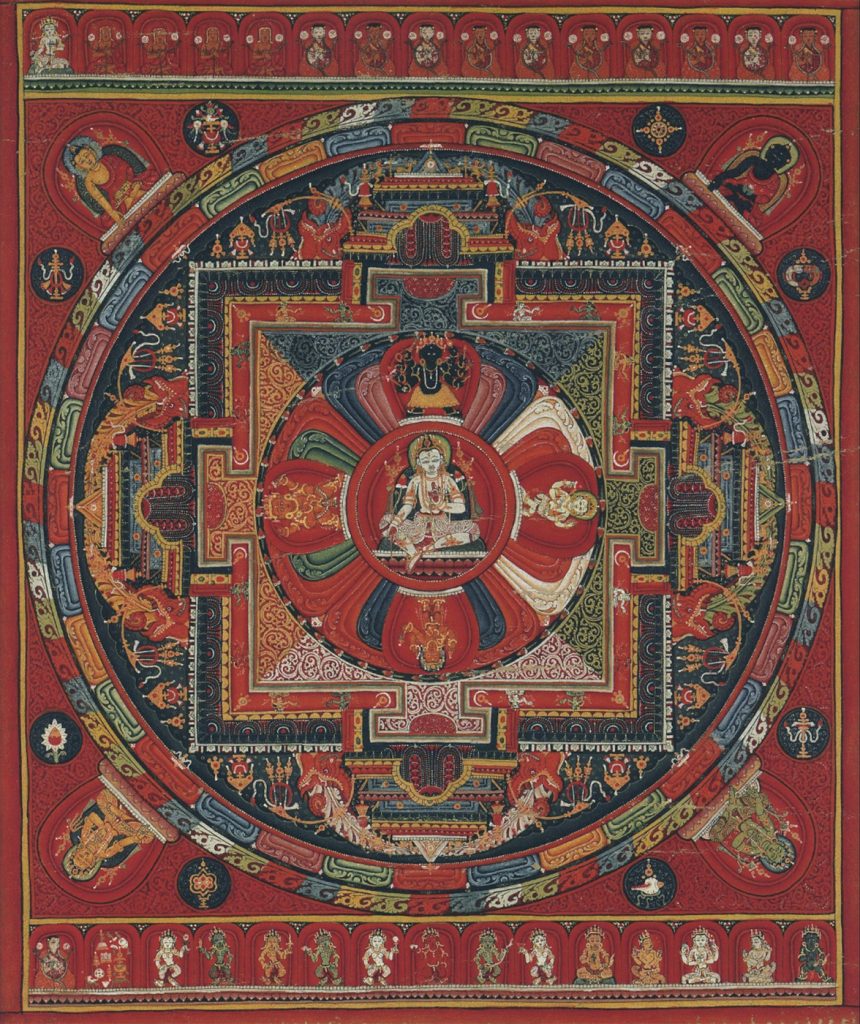

In Himalayan art, we are likely to encounter three types of mandalas. One is the mandala-like object, such as a painting of the bhavachakra, the wheel of life. The next is an offering mandala, which is a flat ritual object, a kind of decorated plate. The third is a deity mandala, which is what we have here.

This small 15th-century painting is intended for private use, and the figure in the lower-left corner is likely the patron who paid for it. Mandalas for temples or monasteries would be larger—easier to see from afar and harder to steal.

The central white figure is Avalokiteshvara. In Mahayana Buddhism, Avalokiteshvara is considered a bodhisattva and the embodiment of compassion. He is a popular figure of veneration and appears in various stories and texts, like the Heart Sutra and the Karandavyuha Sutra, in which he is described as one “who has a hundred thousand arms, who has a hundred thousand times ten million eyes, who has eleven heads.” The sutra even offers instructions on how to construct Avalokiteshvara’s mandala. The well-known mantra Om mani padme hum also appears in the Karandavyuha and is closely associated with Avalokiteshvara.

Unlike many depictions of Avalokiteshvara, the figure shown here has only one face and two arms. Four figures surround him, all facing inward toward him. Rakta Amoghapasha, red in color, is below Avalokiteshvara. To the left is Red Hayagriva, a wrathful male. At the top is Ekajati, female, wrathful in appearance, blue-black in color. And to the right is the female attendant Bhrikuti. She is peaceful and white in color. Their arrangement recalls the five wisdom Buddhas, who represent the qualities of an enlightened mind. It’s as if these figures are in a room together—which, in a sense, they are, since this mandala is an architectural schematic of a palace, with the viewer looking down from above.

Their arrangement recalls the five wisdom Buddhas, who represent the qualities of an enlightened mind.

Just outside the circle of the five deities is a pattern within the square. At the bottom, which faces east, the square is white. The south is yellow, the west is typically red but in this case, blue, and the north is green. These colors make up the floor of the palace but mean much more—remember, each element in tantric art has outer, inner, and secret meanings. For example, green can represent the north, the season of spring, and the element of wind or air. It can also represent fearlessness and protection. All the colors have elaborate systems of meanings.

The T-shape above each deity represents a doorway to the palace with an elaborate lintel. The red band linking the doorways represents a balcony around the palace’s perimeter, on which rest sixteen offering goddesses. Below the goddesses, if you look very closely, there is a band of five colors called the five walls. These correlate by color to the central figures and are part of a mnemonic system of highly complex representation. Outside this balcony of goddesses, there’s a blue band with garlands and tassels, decorations hanging from the roof above the balconies. Beyond that, between the doorways, we see more colorful red-and-gold decorations on the roof.

As is customary in India and Nepal, flower pots and other decorations are placed on the roof. That is what these decorations are. The thin red band that circumscribes the roof decorations can be thought of as the pistil and stamen of a giant lotus, just above which we see its petals; the palace, then, rests upon the lotus. The petals are encircled by flames.

Mandala in Tibetan is kilkhor, which means “circle” or “circumference.” Items outside the sacred circle are purely decorative. The eight auspicious symbols and four buddhas sit outside the circle: Shakyamuni Buddha is in the upper-left corner; the Medicine Buddha, in the upper right; Green Tara, in the lower right; and Vasudhara, the Gold Tara of wealth, is in the lower left.

The top band of figures shows Avalokiteshvara on the left, followed by Indian and Nepalese teachers related to this mandala. The bottom band begins on the left with the patron, dressed as a monk and seated in front of musical instruments. He is followed by the eight offering goddesses: the wealth deity Yellow Jambhala; a group known as the Three Deity Shadakshari Lokeshvara; and finally, the naked black form of Jambhala, a wrathful wealth deity.

Mahayana Buddhist imagery is often narrative-based. But Vajrayana images are all mnemonics with specific meanings grounded in Tantric Buddhism. Thus, mandalas are both visualization tools and detailed maps of tantric teachings with both exoteric and esoteric meanings.

♦

For more on this mandala, https://www.himalayanart.org/.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.