It was my attachment to the past that brought me to Lhasa.

I have always looked for a place where I can find back my memories: the cooing of the doves that woke me up on Sunday mornings at my grandparents’ home; the thrill of that first kiss with the boy I loved, at night in a cemetery on my 16th birthday; walking through the park with my father on an autumn day, the light bright and clean after the rain, while I gathered chestnuts and rubbed them till they shone; the view from my high school math classroom, clouds drifting past rooftops; my wooden toy truck in which I took my dolls on trips to the living room; my first taste of mango; the smell of my grandmother’s talcum powder. . . . How can it all just disappear?

Of all the places in the world, I imagined Lhasa as the city where time stands still and where the past is somehow safeguarded in the vaults of magnificent mountain temples; a place that could possibly even hold the lost moments of my own life. And I keep coming back to Lhasa, reaching out to grasp something that’s not there.

My yearning for Lhasa goes back centuries. Long before any European had reached Tibet, stories circulated about a land in the high mountains of Asia, where mysterious and wonderful things were safeguarded. When in 1507 the German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller published a map of the world, he marked Tibet as the kingdom of Prester John, the mythical ruler whose realm was said to include the Garden of Eden. The image of Tibet as a place of timeless wonder reappeared in the writings of 19th-century spiritualists such as Helena Blavatsky and inspired explorers to set out on expeditions into the Himalayan mountains in failed attempts to locate Shambhala, the Buddhist equivalent of the Garden of Eden. In our rational age, where it seems that every square inch of the surface of the earth has been recorded in satellite photos, we know it is impossible to hide Shambhala behind a mountain range. But the idea of a place outside time and reality has nestled itself into our imagination. It probably entered my consciousness when, as a young child, I read Tintin in Tibet, and as a teenager, the explorer Alexandra David-Neel’s account of her journey to Lhasa. In some recess of my mind, I still carry a little golden city perched on a remote mountaintop—a place where I would like to preserve everything I hold dear. This mythical Lhasa exists, of course, only in my mind. But that did not stop me from trying to reach it.

In the fall and winter of 1999, I spent almost five months in Lhasa, teaching English at a small evening school for adult learners. My stay was not completely legal, because the Communist authorities do not allow unauthorized foreigners to work in the city. But I had persuaded Tsering, a Tibetan businessman, to hire me to teach English at his school. I had met Tsering in the United States when he participated in an exchange program at the same university where I was completing a degree in teaching English as a second language.

This was actually not my first time in Lhasa. I had traveled through the city in 1993, when I backpacked with my husband through China. We spent a week in Lhasa and then continued to Shigatse, the region’s second-largest city. We hitchhiked across Tibet, first to Mount Kailash and then across the Karakorum Mountain range to Kashgar, near China’s border with Kyrgyzstan. That one week I had spent in Lhasa had not satisfied my craving for the city. I had only touched the surface, and I wanted more. I hoped that if I stayed long enough to become a real insider, I could catch the city unaware and penetrate its true essence. That was why I decided to study to become an English-language teacher: I thought of this career as the modern-day version of an early explorer.

I had always wanted to be an explorer. As a student at Indiana University, where I was learning how to teach English to speakers of other languages, I would often sneak up to the sixth floor of the university library, where the 19th-century travel books were kept: dusty leather-bound volumes that hadn’t been opened in decades. I liked to study the crumbling maps that were folded up into the back of those books and look at ancient worlds as I traced with my finger the routes explorers of the past had followed. I have always loved maps—to be able to hold a whole world in your hands and roam from place to place, free from the weight of gravity and time, following rivers from their source to where they dissolve into the ocean, traveling roads that effortlessly connect cities, crossing mountain ranges without blistered feet or shortness of breath. But most of all, I loved the places at the edges of the map, where dragons and sea monsters protected the unknown world from the intrusion of the known . . . magical places where the past and future may have been stored for safekeeping.

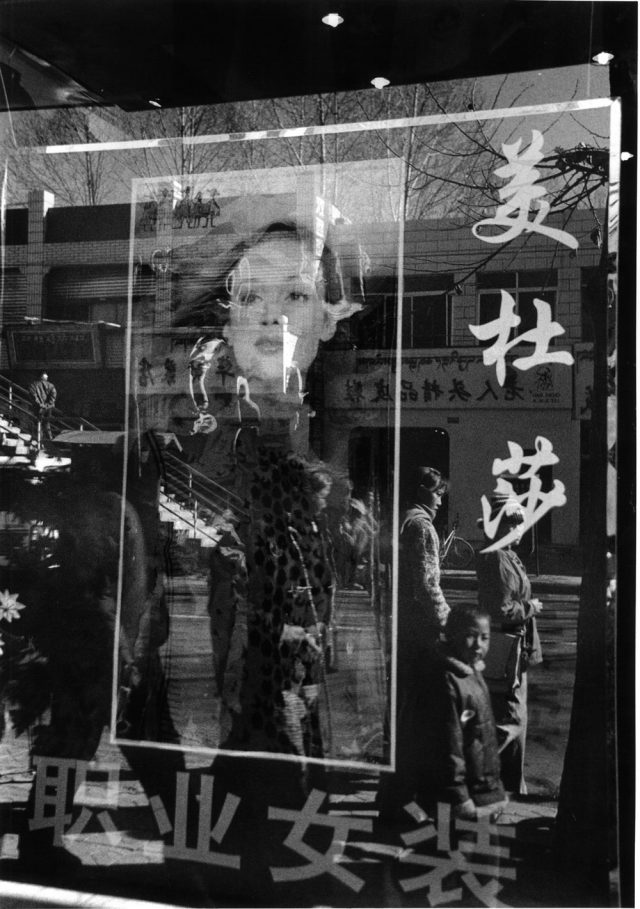

Of course, the Lhasa I encountered was not the center of a magical realm. It was the provincial capital of an underdeveloped region of the People’s Republic of China. Since the Communists had taken over, they had hastily tried to change the old city, which until the 1950s had existed without cars or asphalt roads, into a showcase of industrial progress. Only a few blocks of old mansions and narrow alleys around Jokhang Temple remained as a hint of the past. The Potala Palace, which used to tower on a hill at the outskirts of the city, now formed an island in a grid of straight, broad avenues lined with concrete buildings. The avenues carried only a scattering of traffic, because cars were still a luxury that few people could afford, and anyway the paved roads did not extend much farther than about 20 miles out of the city, where they dissolved into dirt paths.

In 1999, the city was tense. Security cameras looked out over all the public squares, and everybody knew that plainclothes police mingled with the crowds, ready to suppress any expression of dissent against the Party. I had also heard that all mail and email were being read by government censors to detect secret correspondence with Tibetan independence activists abroad. The government was trying to bring wealth and progress to Tibet, to prove to the population that they were better off under Chinese Communism than under the Dalai Lama. But Tibetans told me that this wealth reached only the Chinese migrants who had been encouraged to settle in the city and Tibetans who kowtowed to Communist Party officials.

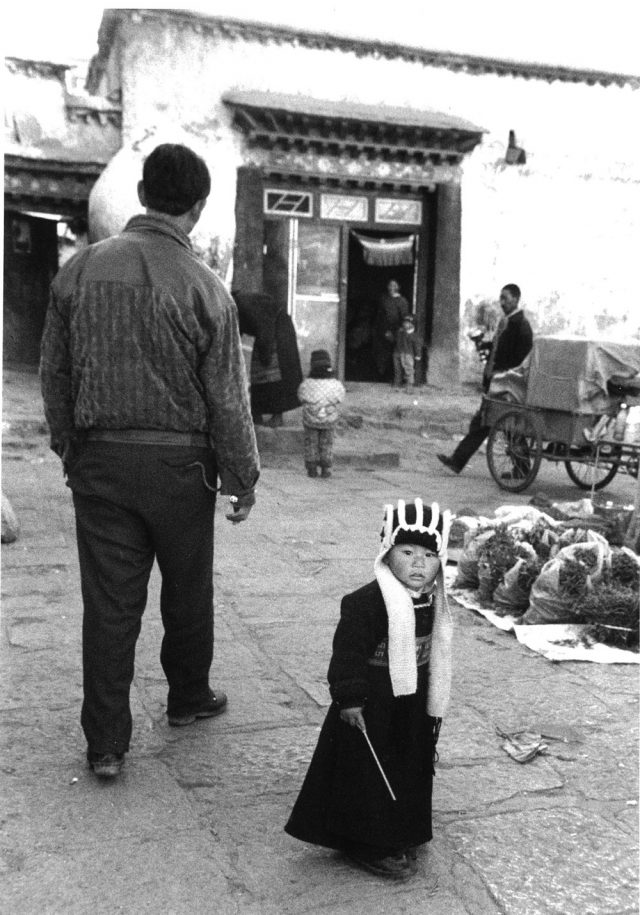

Most of my students were poor young Tibetans from rural areas who had come to Lhasa hoping to find work in the tourism industry once they had learned some English. I spent my evenings teaching simple dialogues from an old textbook about a typical American family who filled their days with magical activities like celebrating Thanksgiving, going to the prom, and planning picnics. During the days, I roamed the city with my camera, photographing old buildings, worn stones, and the faces of pilgrims, trying to capture something that kept eluding me.

These days—17 years later, living with my family in a small town in Vermont—I tend to forget Lhasa. I’m busy raising children; chasing ambitions; earning and spending money; making sure my daughter practices piano; filling up my calendar and crossing things off my to-do list; keeping our refrigerator and kitchen cabinets stocked; trying to convince myself that it all really matters; pursuing happiness . . . managing all those things we do to build a life.

A few months ago, I was startled when I suddenly caught a glimpse of the city in an arcade game. My son attended a friend’s birthday party in a bowling alley in the basement of a shopping mall. The birthday boy had handed out game coins, and my son, who rarely gets to play video games, excitedly claimed a race car contraption that allowed him to drive through imaginary on-screen worlds. Holding tightly to the steering wheel, he swayed in his plastic seat as his Humvee rounded corners in a Tibetan temple complex, zoomed past golden stupas, and skirted rock walls decorated with carved images of the Buddha.

“Westerners still see Tibet as either a reflection of themselves or as a symbol of their yearnings.” This was also Tsering’s criticism of me: that I idealized Lhasa too much.

“Wait! I know that place!” I wanted to shout. “Those rock carvings just past Chushul Bridge—that’s the Nietang Buddha at the entrance of Lhasa valley!” But of course I had never actually seen this Lhasa, this pixelated landscape, so unreal that even when the Humvee crashed into a row of copper prayer wheels, it did not touch them at all.

I know that my longing for Lhasa is a myth I picked up from fantasy novels and movies, but I can’t help being attached to it. Recently I read Imagining Tibet, an anthology of academic articles that analyzed the idealization of Tibet in Western culture—a case study for the analysis of how ideals take shape. In one of the articles in the anthology, Dagyab Kyabgon Rinpoche wrote: “Westerners still see Tibet as either a reflection of themselves or as a symbol of their yearnings.”

This was also Tsering’s criticism of me: that I idealized Lhasa too much. On one of the first days after my arrival—I had just gotten over my altitude sickness—I sat outside in the yard of Tsering’s house with him and his wife, Nidon. We were eating scrambled eggs and toast at a little outdoor table, protected from the sun by a red-and-white striped parasol. The intensely blue sky above us—nothing between us and the stratosphere—reminded me that we were indeed on top of the world. Tsering and Nidon told me with pride that they had designed the house themselves and only recently completed it. Inside their traditionally walled compound they had almost managed to create the illusion of a suburban American home. The southern wall of the house consisted of large windows, giving it a somewhat modernist look, and in the little yard Tsering had managed to grow an almost perfect lawn with grass seeds he had brought back from America. But the sink in the kitchen was not connected to running water, the refrigerator was unreliable because of near-daily power outages, and since Lhasa offered no waste collection, the ditches of the unpaved neighborhood streets were filled with piles of trash.

“You are so lucky to live here,” I said stupidly. Tsering responded that Lhasa was actually quite boring.

“But people dream of living here!” I objected.

“I don’t mind changing places, then,” said Tsering. “You should try living without electricity or modern hospitals.”

When Tsering was a toddler, his father had died of polio. Tsering also developed polio, and the disease had shriveled his legs so that he could walk only with crutches. The village in northern Tibet where he grew up offered no opportunities for a handicapped young man, so his mother decided to send her only child to study at Jokhang Temple, in Lhasa, when he was 13. Tsering’s mother was a deeply devout woman. Besides, becoming a monk was traditionally considered the best chance a rural Tibetan boy had to realize upward socioeconomic mobility. But in Lhasa, Tsering found that monastic life was not what his mother had imagined. The young monks did not receive an education in Buddhist philosophy and spiritual practice. Instead, they were put to work as laborers who maintained the temples and monasteries that attracted so many tourists. Tsering left and opened a computer store. The store had grown first into a computer training center, then into a language school, and now Tsering wanted to start a carpet factory. He said he wanted to help modernize Tibet and create jobs for poor rural Tibetans like himself. Tsering had done very well in Lhasa, which made me suspicious. I couldn’t figure out why he had invited me to teach. Sometimes I worried that he was putting himself at risk by hosting me illegally; at other times I worried that I was a pawn in a scheme I didn’t understand. But I never asked Tsering why he had invited me: when there are spies watching everywhere, some conversations are avoided. It’s very possible that I represented his dream of bringing to Tibet the comforts of Western modernity. Maybe we both carried in our minds imaginary worlds into which we placed each other.

My goal in Lhasa was to capture the past that Tsering wanted to escape. When I walked through the streets of Lhasa with my camera, I hoped to find, just underneath Lhasa’s mundane present, the mysteries described by the explorers. I felt that if I really concentrated, I might be able to coax the past out of the present. Walking along Chingdol Dong Road on my way to evening school, I kept on the lookout for a glimpse of Lhasa’s secrets. The prostitutes who operated from the bars and hairdresser shops along the avenue straightened their miniskirts in preparation for the evening, the karaoke video stores blared out Indian pop music, the sun set behind the concrete buildings of the police barracks, and I aimed my camera at the shadow of a passing bicycle, hoping to capture something that can’t be caught.

Of course, Lhasa was the present, just like any other place where one finds oneself. The Tibet I encountered was no Shambhala, and everyone I met dreamed of change: Sonam wanted to find a husband so she could leave her parents’ home; Mima hoped to become a famous singer; Nyima needed a job so he could rent his own room and would no longer need to sleep on the floor at his cousin’s; Basang hoped her uncle would be released from prison; Dhundup pined for his ex-girlfriend; Li-Xu, a Chinese postal worker from Sichuan who had been transferred to Lhasa, missed his wife and child back home; Phenpa, a monk, wanted to study in Dharamsala; and Tashi secretly longed for Tibetan independence and the return of the Dalai Lama. And I . . . I worried because my visa was about to expire and I was afraid of being deported for working without papers. I felt lonely when I sat by myself in my unheated hotel room (in the middle of winter the hotel stood empty). I was never sure whom to trust; Tsering had warned me to be careful, and I didn’t even know if I could trust him.

Even when I lived in Lhasa, Lhasa was out of reach. Only now, in my memory, I can see again the city I had been looking for. I remember walking around Jokhang Temple with Dauwa, on our way to catch the first bus to Samye. The sun had not yet risen and the puddles of sewage in the streets were frozen solid. A shepherd passed us with a flock of sheep, on his way to the butcher before the market opened. The first pilgrims of the day were walking around the temple, and merchants were setting up shop, their laughter and shouts muffled by the weight of the darkness. Bulky figures stirred underneath the empty booths—these were the poorest pilgrims, who couldn’t afford a hostel and who had spent the night in their thick sheepskin coats under the empty market stalls. From the basement window of a small teahouse sounded the voices of pilgrims and merchants warming themselves with a cup of sweet tea or a bowl of noodle soup. The monks of Gonkar Chode were reciting their morning prayer: a hypnotic drone of rising and falling voices.

I had expected those memories to wait for me until I would be ready to go back, but once more everything continues without me. Time moves on without mercy. I have lost touch with my students. Phenpa sent me a postcard saying he had been transferred to a different monastery, but he included no return address. Sonam wrote to tell me she had gotten married, but two years later she divorced and stopped writing. My emails to Tsering bounce back.

The city I am so attached to in my memory is disappearing and being replaced by something completely new. A few years after I left, a high-elevation railway was completed to link Lhasa with central China. With the influx of more Chinese migrants, the city has swollen to fill the whole valley. Sometimes, when my curiosity gets the better of me, I visit Lhasa on Google Maps to see how it is changing. Places that I remember as austere mountainsides now hold new neighborhoods, and the small village where I once attended a wedding is engulfed by the hangars of the West Lhasa freight train station depot.

I wonder if today’s Lhasa is the city that Tsering dreamed of so many years ago. I once told Tsering that when Lhasa was transformed into a modern city with the most up-to-date conveniences, he too would be nostalgic for the past.

“Possibly,” he said, and shrugged.

I saw Lhasa as a place outside time, a place where I could hold on to the past. But whenever I return, I find a changed city. I remember once more that the true city I am looking for is actually the one of the fantasy novels and video games. And even that Lhasa is the ideal of an ideal. There is nothing to hold on to. The scent of my grandmother’s skin, the shine of chestnuts on an autumn day, a first kiss in a cemetery—they are but disappearing memories.

The only permanence is the permanence that I cling to in my mind: my ideals of how to live; how to be happy; how to raise my children; how to furnish my home; how to better the world; how to fill my time. And these ideals are just as insubstantial as my memory of Tibet.

I know that the Tibet of my imagination has never existed. I know the past is not a place I can return to. But in my memory I keep circling Jokhang Temple on a cold winter morning before sunrise, listening to the hum of monks starting the day with prayer.

A thousand years ago, the Tibetan mystic and poet Milarepa hit upon the paradox that even the Buddhist ideals he preached were no more than the grasping of his mind. In one of his songs, “The Understanding of Reality,” Milarepa preaches the Buddhist path to a group of dakinis, or sky spirits:

. . .in [the realm] of absolute truth

Buddha himself does not exist;

There are no practices nor practitioners,

No Path, no Realization, and no Stages,

No Buddha Bodies and no Wisdom.

There is no Nirvana,

For these are merely names and thoughts.

Matter and beings in the Universe

Are non-existent from the start;

They have never come to be.

There is no Truth, no Innate-Born Wisdom,

No Karma, and no effect therefrom;

Samsara even has no name,

Such is Absolute Truth.

–trans. C. C. Chang

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.