Kudos and Condemnation

Thank you to Neta Golan (“Peace Warrior in the West Bank”) for shedding light on the reality of the situation in the West Bank. Her immense courage in providing an interview with Tricycle on the nature of the Arab-Israeli crisis is to be commended. As an agency for understanding and for positive change in the world, her work is hugely heroic. Tricycledemonstrated tremendous moral courage, as well, in publishing this piece—particularly in a world where acknowledgment of, and responsibility for, the consequences of our actions is so conspicuously lacking in many of our political leaders.

—Brenda Ungerland

Tricycle’s interview with Neta Golan is a perfect illustration of what is wrong with ideology and why it not compatible with Buddhism. In his book The Buddha Taught Nonviolence, Not Pacifism, Paul Fleischman has aptly demonstrated that nonviolence and pacifism are two different things. One should not have to explain to Golan why calling impressionable young human beings to serve as human shields is contrary to everything Buddhism teaches. We have witnessed too many times how idealistic human recruits can be too easily used to achieve cynical political goals.

Instead of advertising this kind of “sacrifice” to young Americans eager for adventure, the International Solidarity Movement could show real solidarity for all victims of violence by convincing young Palestinians that there is nothing glorious about suicide bombings and that violence is counterproductive. Instead of showing solidarity with a known murderer like Arafat by staying in his compound, they could have brought a message of nonviolence to him.

Reacting to the perceived enemy is not the answer. As to advocating the return of refugees to pre-1948 borders, it is totally irresponsible and can only inflict more suffering while bringing an end to the Jewish State. It is sad to see people adopt what they denounce by distorting the teachings.

—Carl Mahe, New Orleans, Louisiana

As a subscriber to your magazine, a small-time contributor, a physician, and a former ordained monk in Thailand, I have been a big fan of Tricycle. That said, let me state emphatically how appalled I was at your interview with Neta Golan, so-called “Peace Warrior.”

First of all, this was essentially a political hit piece, completely one-sided, that had nothing to do with Buddhism. You have a confused Israeli who has rejected her people, abandoned her nation in a time of war (if she had been a Palestinian talking about her own people this way, she would have been summarily executed), who condones terrorism and is, in effect, a mouthpiece for the P.L.O. I have many left-of-center Israeli friends who are not fans of Sharon and who are very willing to give up land for peace, who are offended by the views of Ms. Golan. If you had interviewed Arafat himself, or members of Hamas, Islamic Jihad, etc., the opinions rendered would not have differed much or at all from those of Ms. Golan.

You discredit Buddhists—and your magazine—by associating with and seemingly extolling someone like Golan, someone who would condone terror; who would implicitly support a corrupt, anti-democratic, totalitarian regime that has at its heart the desire to destroy the state of Israel; and who in no way offers a balanced view of the situation. The article in essence was a political jeremiad against Israel.

There was no gain for Buddhism here. There was no unfolding of the Buddhist mind or of Buddhist practice. It was strictly political, and a particularly repugnant and un-Buddhist politics at that. Tricycle was not the proper organ for this article, and by publishing it you have done a great disservice to those interested in peaceful resolution there and elsewhere, to Buddhism in general (which, of course, will survive your indiscretions), and to your magazine. Your judgment was deeply flawed.

—Richard Moss, M.D.

Thank you for your recent article on peace activist Neta Golan. So many Buddhists shrink from political activism, choosing instead to cultivate solipsistic bliss on the cushion; others, ungrounded in contemplative practice, act rashly and to no good end. Golan’s honest attempt to integrate right view and right action is truly admirable; too often, we implement one to the exclusion of the other. It is also remarkable that Golan has been able to show true respect for her country by taking a stand against an occupation that has so deeply compromised its ethical standing among nations.

And congratulations to Tricycle for airing Golan’s views! It can’t be an easy thing for an American publication to do. While the Western press forever focuses on suicide bombings, an increasingly dehumanizing occupation ends the lives of Palestinians every day—and with scant notice. Buddhism, if it does anything, brings us into the world, putting us up against the most intractable moral dilemmas of our time. I look forward to more of the same!

—Maura Brown

Growing up in Israel, well before the 1967 occupation, it used to scare me when I heard mobs of Arabs in neighboring countries chant, “Etbach, etbach el Yahood” (“Kill the Jews!”). At the same time, I couldn’t understand the discrimination I suffered as a child of parents who had survived the Holocaust; nor could I understand Holocaust survivors who discriminated against Jews from Arab countries. I later learned that people simply judge and discriminate against one another because they are threatened by anyone unlike themselves.

Neta Golan’s views and the spiritual perspective are not about a temporary agreement. They are really about implementing nonviolence and inner peace. That’s why they are considered naive, fanatic, and unrealistic.

We are living in cynical times. Most people are skeptical of the possibility of real peace. But until we are willing to admit how untrusting of one another we are, how full of personal fears and hatred, we cannot have real peace. This idea is at the core of all spirituality. Moses, Mohammed, Jesus, Buddha, Gandhi, Dr. King, and many more have all shared this consciousness. It was never popular, because it required looking beyond personal comfort and self-serving needs and transforming a fearful, faithless mindset with fearless insight.

Accepting this reality and having compassion for where we are in the process of our evolution is essential in order to make any real change. It is possible for all people on this planet to coexist and thrive together, if and when our view broadens and we become aware of and have compassion for ourselves as people ruled by the fears, ignorance, and conflicting motives we embody.

—Samuel Kirschner, New York City

Tricycle’s interview with Neta Golan illustrates the inherent problem with “engaged Buddhist” activism. All too often, the advocacy of spiritual principle slips easily into political partisanship. It certainly has done so in Ms. Golan’s case. If Buddhism is about anything, it is about reality. As Buddhists we are taught to see the “whole picture” of reality and all sides of any issue. Ignorance, partisanship, and judgmentalism are not tools of wisdom nor are they spiritual qualities, and they do not enhance practice.

—David K. Gast, La Mesa, California

I was gladdened to see Tricycle’s article “Peace Warrior in the West Bank.” The thoughts and feelings aired onTricycle’s pages since September 11 had, for the most part, left me disheartened. As a native of Iran, I felt betrayed that the compassion of American Buddhists extended so tentatively to the Middle Eastern victims of both Islamic fundamentalism and American foreign policy.

I agree with Neta Golan’s politics. I am glad to see coverage of nonviolent, secular, and democratic movements in the Middle East; hopefully we will also someday see coverage of like efforts of Palestinians and other Middle Eastern people. But I am particularly glad finally to see an article of informative substance on violence in the Middle East. (I can’t help but wonder what memories are brought to the minds of the Dalai Lama and Thich Nhat Hanh by such things as foreign occupation and war waged by the U.S.) I truly believe that being informed deserves more prominence in American Buddhist “skillful means” training—not to mention in overall waking-up efforts.

—Maryam Pirnazar, San Francisco, California

Spotlight on Spot

“Putting Spot Down” has been one of the few articles in Tricycle to irritate me, and I am a longtime subscriber. First, as a veterinarian, I do not make a living putting animals down, although it is one of the more expensive single shots I give. Second, I do not enjoy putting animals down, but I have lived with the results of not doing it. I think Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche has lost his way if he is worried about whether we can accurately see the circumstances of this life or the next. This goes against the Buddha’s idea of living in the moment.

I think Baker Roshi has it wrong, too. Animals are not “blissed out”—they are truly living in the moment. If a horse is suffering, what does he gain if I insist that the owners let him die a natural death? The fact that I kill Dzigar’s fly—or a horse—does not give it bad karma. Animals are truly innocent, and to worry about their future lives is to lose our mindful way. Finally, when an animal is in pain, no relief comes from drugs. They keep right on hurting. And using alternative medicine is a classic example of an owner’s letting the animal suffer out of his own reluctance to let the animal go.

I probably sound angry, but I am really trying to be mindful and take into account what I see on a weekly basis. Buddhism is supposed to be nonviolent. To put Spot down is violent, but to allow him to suffer is also violent. We must all decide for ourselves which is more violent. But we must make this decision in the moment, without considering some ethereal future. Once it is done, it is done.

—David R. Smith, D.V.M., Ravensdale, Washington

The Twain Shall Meet

I enjoyed reading P. B. Law’s Buddhist parody of Huckleberry Finn (“Huck & Tom’s Buddhist Adventure”). Law did an excellent job of capturing the tone and spirit of Twain’s classic narrative, and by puncturing holes in some of the pomposities of American Buddhism, he has carried on Twain’s satirical mission.

However, I wonder if Law and your readers are aware of just how much Twain’s religious attitudes have in common with the Buddha’s teachings. Both were skeptics of religious orthodoxy who valued direct, personal experience over received tradition. Both also dedicated their lives to subverting the false assumptions that define what most people consider to be reality.

Consequently, both Twain and the Buddha have been accused of solipsistic nihilism by the people who cling to those false assumptions. Just as Buddha’s teaching on anatta (no-self) has been dismissed as a negation of reality, Twain’s writing (especially in his later years) is cited by critics as evidence of his despairing attempt to nihilistically “detonate the universe.”

As Sri Lankan Buddhist and author Walpola Rahula points out, though, anatta should not be considered nihilisitc, but instead it should be recognized as dispelling the false belief in a nonexisting, imaginary self. Neither should Twain’s late writings, in my opinion, be perceived as negative. In fact, in his last novel, The Mysterious Stranger, after subverting various fictions throughout the text and ultimately his own narrative, Twain’s conclusion that “life itself is only a vision, a dream” is basically the same liberating insight that Buddha taught.

Although I don’t know that Twain would have considered himself a Buddhist (he would have had too many problems with the prohibitions on drinking and swearing), I do believe he ultimately lit out for the same spiritual territory that Gautama did many centuries before.

—Dwayne Eutsey, Easton, Maryland

Loving the Indder Enemy

I have been imprisoned for fifteen years and have practiced Zen under the Lotus Flower sangha, an affiliate of Zen Mountain Monastery in Mt. Tremper, New York, during four of those years. Our sangha has had the privilege of reading Tricycle through the grace of our Sensei, who comes into the prison regularly. I have read the Summer 2002 issue and would like to share my view on the articles appearing in “On Practice: Loving the Enemy.” The teachings offered have provided some insight and understanding with regard to living more peacefully regardless of feelings towards those we consider our enemies. This has been an extremely challenging feat for me in prison. Oppression, exploitation, and violence are commonplace, as is the unspoken strategy of segregating prisoners, preventing unity among races, classes, cultures, and religions. How can a practitioner be expected to “see the perfection” and “realize the self and other as one” in this atmosphere?

Sometimes it is much easier to simply place others in the categories of friend, neutral, or enemy. At least this way I know where I stand when around any particular category and I know how to respond appropriately in a given situation. In prison, compassion is seen as a sign of weakness and makes non-opposition difficult to practice. I believe one of the surest ways to begin on the path toward loving the enemy in this environment is best described by the Dalai Lama: the inner enemy must first be battled and trained. The ego is the worst enemy of all and is the first to arise during any form of conflict. Awareness of that “mighty fiend,” my “dark, defiled emotions,” is the first step towards liberation. Once I can discipline the inner enemy I can thereafter handle the outer enemy more positively and efficiently in accordance with my vows.

Thank you for the insight. It would be ideal if in future issues you could provide teachings suited to a prison setting. The Buddha Way has been very helpful to me in dealing with issues that arise within and without. I have become a better person since I began Zen practice, evident from how I perceive things and interact with others.

—Eddie Cuadrado, Green Haven Correctional Facility, Stormville, New York

Faith Uncovered

As an anthropologist and someone with a personal commitment to Buddhism, I was interested to read Faith Adiele’s recent article on her experiences joining a Buddhist nunnery overseas (“A Green and Gold Place”). However, I was concerned that her statement that “true anthropology require[s] undercover work” might leave readers with the impression that deception is a common part of anthropological practice.

In fact, it is standard practice in our discipline to be as honest and straightforward as possible with people about our reasons for doing research among them. This honesty is normally essential to creating the relationships with others that make real learning about other ways of life possible. Ms. Adiele was a student, and she appears to have followed her heart and her spirit in joining a religious community. However, I want Tricycle readers to know that taking vows in a religious community purely for research purposes would normally be considered neither ethically sound nor methodologically wise.

—Dr. Hildi Hendrickson, Chair, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Long Island University

Our Slip

An editor might have caught Michael Attie’s error in the introductory paragraph to “Memoirs of a Lingerie Monk.” Hindus traditionally divide life into four (not three) stages, or ashramas: (1) brahmacharya (the state of receiving religious instruction; (2) grhastha (that of householder); (3) vanaprastha (that of forest dweller); and (4) samnyasa (renunciation). I suspect Attie has understandably conflated the third and fourth stages, although of course the first stage is hardly bereft of “spiritual seek[ing].” Indeed, keeping in mind that these are “ideal-typical” categories, all four stages may be infused with the “spiritual,” although the fourth, in several respects, “transcends” typical social constraints and rules.

—Patrick S. O’Donnell, Santa Barbara, California

Tricycle welcomes letters to the editor. Letters are subject to editing. Please send correspondence to:

Tricycle: The Buddhist Review

92 Vandam Street

New York, NY 10013

Fax: (212) 645-1493

E-mail address: editorial@tricycle.com

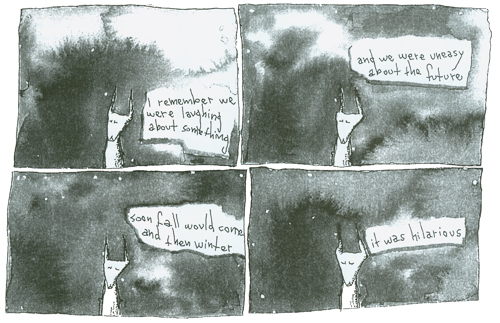

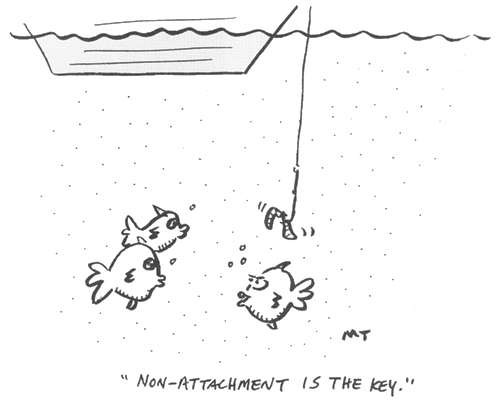

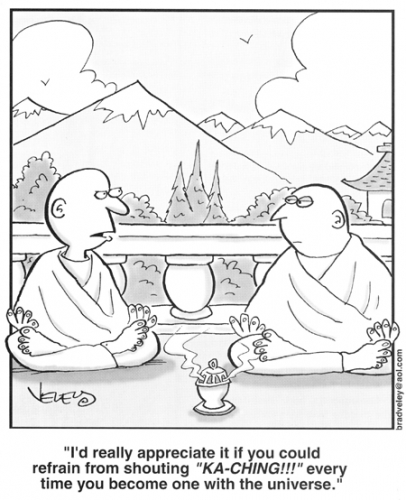

Images © Neal Crosbie, Mike Taylor, and Bradford Veley

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.