Praise to you, violent god of the Yellow Hat teachings, Who reduces to particles of dust Great beings, high officials, and ordinary people Who pollute and corrupt the Gelugpa doctrine.

– From “Praise to Dorje Shugden,” quoted by Zemey Rinpoche (1927-1996)

The so-called Drakpa Gyaltsen* pretends to be a sublime being. But since this interfering spirit and creature of distorted prayers Is harming everything, both dharma and sentient beings, Do not support, protect or give him shelter, but grind him to dust.

– The Fifth Dalai Lama (1617-1682)

*The Drakpa Gyaltsen was the Fifth Dalai Lama’s rival. Dorje Shugden is considered to be his reincarnation, resurrected to oppose the involvement of Gelugpa monks with Nyingma teachings.

“A wrathful deity,” announced the London Independent with barely concealed irony on February 17, 1997, “is the main suspect for three murders in Dharamsala, the Himalayan ‘capital’ of Tibet’s government-in-exile.” Two weeks earlier, Geshe Lobsang Gyatso, the principal of the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics, and two students had been stabbed to death. Despite exhaustive investigations by the Indian police, the case is still unresolved. Although arrest warrants for two suspects have been issued, the police believe the killers have gone underground in either Nepal or Tibet. Interpol has been called in to help find them. And although Shugden supporters have vigorously criticized the media for affiliating them with the murders, the very widespread assumptions themselves reflect both the historical and emotional nature of the dispute.

On July 6, 1996, another British newspaper, the Guardian, carried a front-page story under the heading “Smear campaign sparks safety fears over Dalai Lama’s UK visit.” The article described demonstrations on the streets of London where hundreds of British Buddhists “chanted anti-Dalai Lama slogans and carried placards saying ‘Your smiles charm, your actions harm.’” The Nobel laureate was accused by an organization called the Shugden Supporters Community of being “a ruthless dictator” and “an oppressor of religious freedom.”

These tragic and bewildering events have brought to the attention of the world a long-standing arcane feud within the Tibetan Buddhist community that centers around the protector god Dorje Shugden. While feeding the West’s seemingly insatiable fascination with all things Tibetan, the murders and demonstrations have exposed a dark and troubling underside of a tradition often seen as a beacon of wisdom and compassion in a spiritually confused world. Even if it turns out that the killings were, in fact, part of a Chinese campaign to intensify discord in the Tibetan community in exile, this still means that Beijing has been able to exploit a bitter dispute that the Dalai Lama and his supporters such as the late Gen Lobsang Gyatso remain powerless to resolve.

To understand the complex origins of this dispute, it is necessary not only to trace an outline of Tibetan history since the seventeenth century, but also to grasp some of the doctrinal and philosophical issues that have divided the population since Buddhism was established in Tibet in the eighth century.

On the twenty-eighth day of the seventh lunar month of 1642, the Fifth Dalai Lama dreamed that two lamas of another sect—the Nyingma—gave him an initiation in a chapel of his palace at Drepung monastery. One of the lamas handed him a ritual dagger and at that very moment the Dalai Lama had the feeling of being spied on through a window by monks of his own Gelugpa order. He reflected that if the Gelugpa monks criticized him for receiving teachings from the Nyingma lamas, he would stab them with the dagger. He rushed out to confront them, but they already seemed subdued. At that point he woke up.

Earlier that same year, the twenty-six-year-old Dalai Lama had been conferred with supreme authority over all Tibet by the Mongol Gushri Khan, thus inaugurating the dynasty of the Dalai Lamas. This step was achieved when the armies of the Mongol Khan defeated the king of Tsang, the backer of the Dalai Lama’s chief rival for power in Tibet, the Karmapa (a senior lama of the Kagyu order). While their military victory ended years of civil conflict in Tibet and unified the country under the Gelugpa order, it also exposed tensions among the Gelugpas themselves—already hinted at in the Dalai Lama’s dream of three months later.

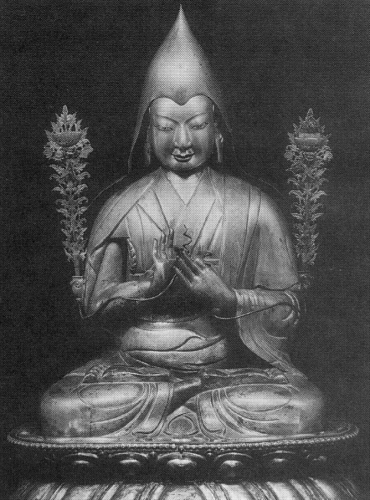

The Gelugpa tradition had been founded more than two hundred years earlier by the remarkable monk, scholar, and yogin Tsongkhapa, who drew from all Tibetan Buddhist traditions of his time to create a compelling new synthesis of doctrine, ethics, philosophy, and practice. The first Dalai Lama was a leading disciple of Tsongkhapa, and as the influence of the Gelugpas grew steadily over the next two centuries, the Dalai Lamas emerged as important spiritual figures within the school. When the fifth in the line became head of the Tibetan state, the institution of the Dalai Lama suddenly assumed unprecedented political power.

Although the Fifth Dalai Lama was a Gelugpa monk, as head of state he carried not only the mantle of Tsongkhapa’s reformed Buddhist order but also that of a thousand years of Tibetan history. This would have been particularly poignant for him, since he was born into a family whose ancestral home overlooked the tombs of the early Tibetan kings in the Chonggye Valley and who were still associated with the Nyingma tradition. The Nyingmapas (“Ancients”) had been instrumental in introducing Buddhism to Tibet at the time of those early kings and in first defining the buddhocratic nature of the state. Throughout his life the Fifth Dalai Lama maintained a strong allegiance to the Nyingma school and a mystical rapport with its founder, Padmasambhava, who appeared to him in dreams and visions.

The Fifth Dalai Lama’s assumption of this long and complex historical identity would not have sat easily with the ambitions of a Gelugpa hierarchy intent on creating a buddhocratic state founded explicitly on the teachings of Tsongkhapa. It seems that this conflict led to the death of the Fifth Dalai Lama’s rival Drakpa Gyaltsen, shortly after the Dalai Lama’s return from a state visit to China (suggesting the possibility of a palace revolt during his prolonged absence). Thereafter, Dorje Shugden was recognized by those Gelugpas who opposed the Dalai Lama’s involvement with the Nyingma school as the reincarnation of Drakpa Gyaltsen, who had assumed the form of a wrathful protector of the purity of Tsongkhapa’s teachings. They also regarded him as an emanation of the bodhisattva Manjushri.

After the death of the Fifth Dalai Lama in 1682, the controversy between these factions of the Gelugpa school slips into the shadows, and we hear only occasional references to Dorje Shugden for the next two hundred years. The Sixth Dalai Lama was unsuited to public office and was arrested and killed by the Mongols. After the Seventh Dalai Lama was returned to Lhasa in 1720 by the Manchus, the government of Tibet passed into the hands of a regency composed initially of powerful aristocrats and then, for 113 years, of senior Gelugpa lamas. Of the six Dalai Lamas who lived during this period of regency, the last four died before the age of twenty-one, thus failing to assume leadership of Tibet for more than a year or so.

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama came to power at the age of nineteen in 1895. Having survived an assassination attempt (his former regent had concealed deadly mantras in the Dalai Lamas boots), he found himself charged with the daunting task of leading Tibet into a rapidly changing world. He proved an able leader who sought to introduce a modest program of reform, only to be thwarted by aristocrats and senior lamas. He was also a keen practitioner of Nyingma teachings. He had several teachers from the Nyingma school, practiced with them in the Potala Palace, and wrote commentaries to the Nyingma texts by his predecessor, the Fifth Dalai Lama.

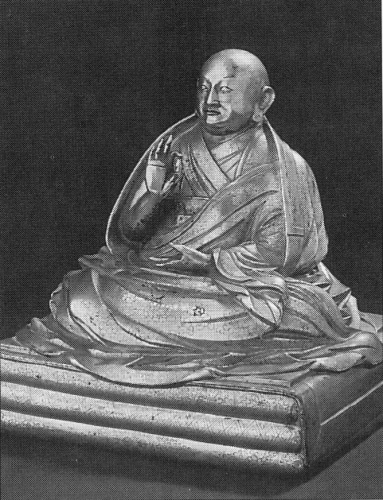

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama’s openness to the Nyingmapa was in marked contrast to that of Pabongka Rinpoche, the most influential Gelugpa lama of the time, whose authority rivaled that of the Dalai Lama. Pabongka inherited the practice of Dorje Shugden from his mother’s family, and as a young man also received transmissions from Nyingma lamas. After a serious illness he became convinced that the disease was a sign from Shugden to stop practicing Nyingma teachings, which he did. Although he promoted the practice of Shugden, he was ordered by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama to stop invoking the deity on the grounds that it was destroying Buddhism. Pabongka then promised “in the core of my heart” never to propitiate Shugden again. He evidently changed his mind, though, and subsequently passed the practice on to his disciples.

The present Dalai Lama, born in 1935, was introduced to the practice of Dorje Shugden by his junior tutor Trijang Rinpoche, a leading disciple of Pabongka. This was a time of great political turmoil in Tibet. The reliability of the state oracle at Nechung had been thrown into doubt, and some believed that the government should switch its allegiance to the oracle representing Dorje Shugden. The regent, Reting Rinpoche, was forced to resign, only to return to launch an unsuccessful coup in 1947. The Chinese Communists arrived in Lhasa in 1952. The Dalai Lama, his tutors, and 100,000 Tibetans fled to India in 1959, possibly—according to some lamas—on the advice of the Shugden oracle.

In 1973, a senior Gelugpa lama called Zemey Rinpoche published an account of Dorje Shugden that he had received orally from his teacher (and the Dalai Lama’s tutor) Trijang Rinpoche. This text recounts in detail the various calamities that have befallen monks and laypeople of the Gelugpa tradition who have practiced Nyingma teachings. Those mentioned include the last three Panchen Lamas, senior officials of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama’s government, Reting Rinpoche, and even Pabongka himself. In each case, the illness, torture or death incurred is claimed to be the result of having displeased Dorje Shugden. The publication of this material was condemned by the Dalai Lama, who was then engaged in Nyingma practices himself under the guidance of the late Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. But the Dalai Lama’s views about Dorje Shugden began to shift and led to his first statements discouraging the practice in 1976.

Each time a Dalai Lama has come to hold effective political office, a controversy has erupted around Dorje Shugden. A similar pattern has repeated itself during the rules of the Fifth, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth Dalai Lamas. This conflict has inevitably been articulated in the vivid, yet (to outsiders) bewildering language and imagery of Tibetan culture. It reflects a struggle between two opposing visions of how best to lead sentient beings to enlightenment, preserve the Buddha’s teaching, and maintain the integrity of the Tibetan state. Representatives of both sides have included wise, moral, and saintly men who have led exemplary Buddhist lives. Some, such as Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche and Trijang Rinpoche, admired and respected each other. As in the case with everything to do with Tibet, the line between religion and politics is blurred. The dispute over Dorje Shugden is neither an exclusively religious nor a fundamentally political one. It is both.

Who are these invisible beings that appear to Tibetan lamas in dreams and visions, speak through oracles, predict the future, inspire awe and terror, bless those who worship them and incur misfortune on those who don’t? The Tibetan term for such beings is lha. Lha means “deity” or “god.” Such gods are both Indian and Tibetan in origin and constitute a pantheon as complex and arcane as that of ancient Greece and Rome. Yet with the advent of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, there appears an altogether different kind of god. These are buddhas and bodhisattvas, awakened beings who have vowed to work ceaselessly and in myriad ways for the welfare of beings. While not mere gods—who for all their powers are just another class of unawakened sentient being—they assume the form of gods for the benefit of others.

Tibetan Buddhists regard these gods, whether of the unawakened or awakened variety, as conscious, autonomous beings, every bit as real as you or I. The Dalai Lama, who so successfully presents Buddhism in the Western media as rational, pragmatic and compatible with modern psychology and science, appears to believe in the power of these gods. In a statement issued in English by the Tibetan government in exile in 1996, he is quoted from a speech to an audience of Tibetans as saying: “It has become fairly clear that Dolgyal (i.e., Shugden) is a spirit of the dark forces.”

The Dalai Lama is not speaking here as a modern religious leader trying to persuade some of his superstitious flock to relinquish an outdated worldview. He is engaged in an emotive debate about whether a particular god is a powerful but deluded sentient being or a buddha who has assumed the form of a god. Such is the perceived power of Dorje Shugden that both Gelugpas who invoke him and Nyingmapas who fear him will not even let his name pass their lips This atmosphere of secrecy and implicit danger serves to affirm for Tibetan Buddhists their view of an invisible polytheistic reality intersecting with the human world.

Although this worldview may be unfamiliar, it is not intrinsically stranger than that of Christians and other religious believers who currently lack the exotic prestige Tibetan lamas have for Westerners. The main difference between it and other religious worldviews is that Buddhists, at least in theory, know all these gods to be empty of any inherent reality. Everything, they would say, is merely an appearance as ephemeral and insubstantial as a dream. Such statements have led some in the West to assume that the gods of Tibetan Buddhism are no more than archetypal symbols: they perform a psychological function in the process of spiritual transformation, but only the naive would say they represent beings independent of the practitioner’s own mind. Yet however persuasive this kind of Jungian interpretation may be, it is not how most Tibetan lamas understand the world they inhabit.

For gods to be empty of inherent existence does not mean that they cannot be autonomous beings capable of making choices and existing in their own heavenly realms. In this sense they are no different from humans, who are likewise empty but perfectly capable of making decisions and living their own unique and fallible lives. The doctrine of emptiness only teaches us to see ourselves and the world in a way that frees us from the reification and egoism that generate anguish. To say the world is empty neither affirms nor denies the claims of any cosmological theory, be it that of ancient India or modern astrophysics.

To establish an authentic Buddhist state on the basis of this vision, however, requires ensuring that a correct view of emptiness be upheld by those in power. Such responsibility would be a necessary outcome of the bodhisattva’s compassionate resolve. For that reason, the Fifth Dalai Lama’s government proscribed the teachings of the Jonangpa school, which taught that emptiness implied a transcendent absolute reality that inherently exists. Texts of the Jonangpa school were confiscated and its monasteries turned over to the Gelugpa, to be run by Gelugpa monks. It seems other factions in the Gelugpa order would have liked to have taken similar measures against the Nyingma school.

One can understand why the Dalai Lamas would tolerate and even embrace Nyingma views in order to honor the historical heritage of Tibet, to affirm unity among the diverse communities of the Tibetan nation, even to be true to their own spiritual intuitions, But however justified such a position might be in personal or political terms, it should not obscure the real and potentially divisive philosophical and doctrinal differences that exist between the Nyingma and Gelugpa ideologies.

The Nyingma teaching of Dzogchen regards awareness (Tib., rig pa) as the innate self-cognizant foundation of both samsara and nirvana. Rig pa is the intrinsic, uncontrived nature of mind, which a Dzogchen master is capable of directly pointing out to his students. For the Nyingmapa, Dzogchen represents the very apogee of what the Buddha taught, whereas Tsongkhapa’s view of emptiness as just a negation of inherent existence, implying no transcendent reality, verges on nihilism.

For the Gelugpas, Dzogchen succumbs to the opposite extreme: that of delusively clinging to something permanent and self-existent as the basis of reality. They see Dzogchen as a return to the Hindu ideas that Buddhists resisted in India, and a residue of the Ch’an (Zen) doctrine of Hva-shang Mahayana, proscribed at the time of the early kings. Moreover, some Kagyu and Nyingma teachers of the Rime (“impartial”) revival movement in eastern Tibet in the nineteenth century even began to promote a synthesis between the forbidden Jonangpa philosophy and the practice of Dzogchen.

For the followers of Shugden this is not an obscure metaphysical disagreement, but a life-and-death struggle for truth in which the destiny of all sentient beings is at stake. The bodhisattva vow, taken by every Tibetan Buddhist, is a commitment to lead all beings to the end of anguish and the realization of buddhahood. Following Tsongkhapa, the Gelugpas maintain that the only way to achieve this is to understand non-conceptually that nothing whatsoever inherently exists. Any residue, however subtle, of an attachment to inherent existence works against the bodhisattva’s aim and perpetuates the very anguish he or she seeks to dispel.

Moreover, protectors such as Dorje Shugden exert an enormous power over the minds of Tibetan Buddhists—be they erudite lamas, simple Bhutanese peasants or educated Westerners. While lamas teach that taking refuge in the Buddha, dharma, and sangha is the only protection a Buddhist requires, they invariably supplement this with initiations into and practices of a range of protector gods. After all, the Land of Snows could be a harsh and frightening place. Tibetans lived in an awesome, sparsely inhabited landscape with a fierce climate, psychically populated by numerous spirits, demons and gods. The very survival of communities required a powerful sense of family, tribal and religious loyalty. In a psychoanalytical sense, Dorje Shugden could be seen as the personification of a specific set of fears and loyalties in the form of a god. But for Tibetan Buddhists he is not just a metaphor. He is a real, living god/buddha whose displeasure can wreak havoc on human beings.

At a certain point in their practice, those who rely on Dorje Shugden will ritually “entrust their lives” (Tib., srog gtad) to him. This is not a step taken lightly. Until 1976, the current Dalai Lama offered daily prayers to Shugden, but was never initiated. On the advice of the Nechung oracle, which decreed Shugden a divisive force in Tibetan unity, he began to warn against the deity’s worship. When he requests people to renounce Shugden, the Dalai Lama challenges a deeply felt loyalty and raises the possibility of frightful retribution. “Nothing will happen,” he has had to reassure Tibetans. “I will face the challenge. . . . No harm will befall you.”

Although some Gelugpas have heeded his advice, others have not. Those loyal to Dorje Shugden could well believe that the misfortunes to have befallen the institution of the Dalai Lama, even the tragedy of Tibet in the twentieth century, arise from a failure to heed the advice of their protector who “reduces to particles of dust great beings, high officials, and ordinary people who pollute and corrupt the Gelugpa doctrine.” For the Dalai Lama to denounce Dorje Shugden may confirm for them that he is simply part of the problem.

Speaking of the British monarchy more than a hundred years ago, Walter Bagehot warned of “letting daylight into magic.” This is happening in Tibet today as the media peer into events which formerly only a handful of lamas and their advisors would have been privy to. The obscure wrangling and intrigue surrounding the reincarnations of the Karmapa and the Panchen Lama are disseminated through newspapers, Web sites, television, and radio within hours of having taken place, while grisly murders in Dharamsala promptly lead to Dorje Shugden’s dissection in he pages of Newsweek. The Dalai Lama in particular has used the media to great effect, but the fascination he has both drawn upon and stimulated now threatens to turn the magic of Tibet into mere spectacle.

If we strip away the exotic veneer of this Tibetan Buddhist dispute, we are confronted with questions that concern the very nature of the dharma and its practice. In the West we are fond of portraying Buddhism as a tolerant, rational, non-dogmatic and open-minded tradition. But how much is this the result of liberal Western(ized) intellectuals seeking to construct an image of Buddhism that simply confirms their own prejudices and desires?

Historically, Buddhists everywhere have tended not to exhibit the pluralist, postmodern values we might imagine them to possess. All Buddhist traditions make claims to truth, and when those claims have contradicted one another, then passionate, prolonged, even violent disputes have ensued. All the more so is this the case in the polytheistic buddhocracy of Tibet, where a very human dispute between different doctrinal camps has also inevitably been a struggle among the gods. Each side has invoked its own invisible beings for blessing and protection, summoned its own oracles for guidance from them, and been convinced that it was acting out of compassion for the welfare of all beings. Tibetan lamas take their disputes seriously not merely because of short-term political gain. Many of them act out of deep and sincere passion for what they hold to be true.

Yet history also teaches us that Buddhism possesses a remarkable capacity to reimagine itself in response to the challenges posed by new historical and cultural situations. Its protean forms are testimony to the survival of a way of life that has traveled throughout Asia and is now taking its tentative first steps in America and Europe. If it is to survive, it will have to find a way of preserving the heartfelt, single-minded commitment at its core within multicultural societies that reject the totalizing and potentially repressive demands of any single claim to truth.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.