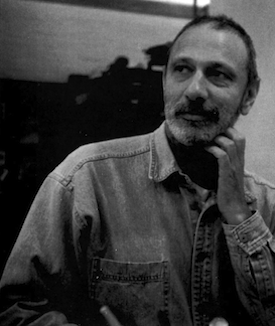

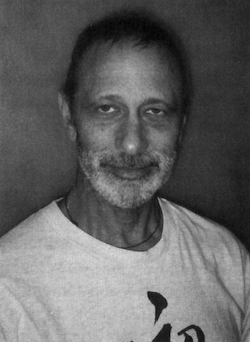

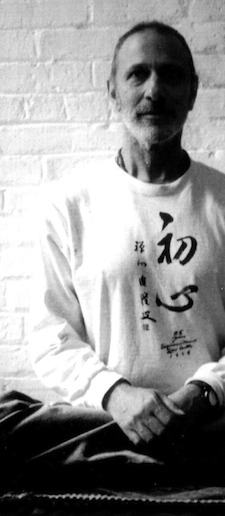

Rick Fields, poet, writer, student of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche and other teachers in the Kagyu and Nyingma traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, was diagnosed with lung cancer in 1995. Currently editor-in-chief of Yoga Journal and a contributing editor to Tricycle, Fields lives in Fairfax, California, with his partner, Marcia Cohen. He is the author of several books including How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America (Shambhala) and Code of the Warrior (Tarcher). This interview was conducted by Helen Tworkov in California, in May 1997.

TRICYCLE: When you were first told that you had cancer, what did you do?

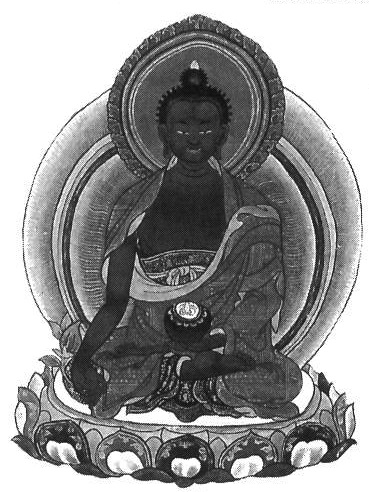

FIELDS: Just by chance, that night a Tibetan lama was giving a Medicine Buddha teaching and I went. Part of it is that when you have a sickness, you view it as a chance to take on the karma of the sickness of other people in a bodhisattva fashion. That’s very different from a Western notion of getting sick. The bodhisattvic viewpoint turns everything around. This is Vajrayana practice, to take any situation that occurs and make it part of the path. Not just good situations, but any situation becomes part of the path. Illness becomes part of the path. You can say, “May this sickness I have help me to take on the sickness of all other people who are suffering in the same way so that they are free from their suffering.” By doing this, you attack your self-pity and your egotism and that basic question that arises when we get sick: “Why me?”

TRICYCLE: How have your teachers responded?

FIELDS: Usually the first thing they have said is, “Everybody has to die. Death is real.” Rather than, “We can cure this and you’ll be all right.” There was a very bare recognition that, “Well, what do you expect? You were born, so you’re going to die.” Almost like, “Yes, what’s the big deal?” Then a little deeper along comes the idea that, “You’re lucky because it’s good for your practice!’

TRICYCLE: Lucky because you are a practitioner?

FIELDS: Lucky because there is time to prepare, whether you are a practitioner or not. The usual notion in the West is, “Oh, so-and-so is very lucky that they died in their sleep or had a heart attack or sudden death.” But cancer is particularly good because you usually have time to contemplate the whole thing and work with it. Part of the Kagyu Ngundro practice [of Tibetan Buddhism] involves repeating the Four Reminders. The second, in the translation that Trungpa Rinpoche used, is

Death is real,

Comes without warning

This body will be a corpse.

Death is the only certainty in our lives. Yet much of our culture is organized to help us ignore death. So from that point of view, a terminal illness can be very helpful to your spiritual practice. But that leaves you with the questions of what to do and how to handle it. There are healing teachings that address staying alive but at the same time, there isn’t this denial of death. Still, this idea that dying is a wonderful experience is a sort of double-edged sword: it is, or can be, but most of us want to stay alive as long as possible. Certainly I do.

TRICYCLE: I was under the impression that at a certain point, you became quite annoyed with that phrase—”It’s good for your practice.”

FIELDS: In Buddhist centers the term is often used as a joke. When anything you don’t like or want happens people say, “That’s good for your practice.” Any disaster that happens is good for your practice. Which is obviously true, but it’s sort of like, “Oh yeah, well, why don’t you do this and it would be good for your practice.” It’s annoying if it’s an automatic response and not really being with what the person is experiencing. Maybe it’s good for your practice, but it might be bad for your life. You’re talking about something that can kill you. This opens up so many different kinds of questions of surrender and acceptance and fighting. My first reaction was “all hands on deck” because this cancer had been misdiagnosed for over a year and had become very dangerous, so I had to do something pretty aggressive and drastic. But you never know what’s going to happen. You could have a car accident on your way to some wonderful healer. “Death comes without warning. This body will be a corpse.”

TRICYCLE: Are you interested in your prognosis?

FIELDS: No. My attitude is ‘Tm going to live until I die.” Which is all anyone can do. I don’t see the value of having someone say, “You have four months to live.” And I don’t want to give that weight to any one person’s opinion, whether they’re seemingly an enlightened spiritual person or super Ph.D. or M.D. Fortune telling has never interested me.

TRICYCLE: How do you walk between acceptance of death and the trying to stop or heal a socalled terminal illness?

FIELDS: Eventually all of us will die. Death is real, it comes without warning. And this body, this particular body, will be a corpse. Buddhism has always been very consistent about that. The first doctors told me the statistics for stage-four metastatic lung cancer, which is what I have, are not very good. Once I found that out, I told the doctors that I’m not interested in hearing about them. What good would it do me? I’m going to live until I die. Whether the doctor tells me I have four months to live or five years, I’m going to live until I die. And the doctor is going to live until he dies. He thinks he knows when I’m going to die but he doesn’t even know when he’s going to die. If I die fighting it, fine. I’m going to die sooner or later anyhow.

TRICYCLE: What does “fighting it” mean?

FIELDS: There are different levels. It’s more of a philosophical than a medical question: whether to emphasize quality of life or very aggressive treatment. My first decision with the oncologist was to fight this as aggressively as possible. The second was to do radiation and chemotherapy together, which is stronger. But the side effects are more serious. I said, “Well, it seems that if I don’t do something drastic that the cancer is likely to kill me, so let’s do both.” And both he and the radiologist advised me against doing it because they believed the side effects were not worth what might be a slight advantage. My Chinese-Jewish doctor who has been my advisor through this whole process thought it was worth doing. So I was in the odd situation where my so-called alternative practitioner was recommending “pull out all the stops” of conventional medicine and my conventional doctors were acting more like “We don’t know if it’ll work.” They were being much more cautious. So that’s one way that I mean fighting.

TRICYCLE: When you fight cancer, does cancer become something separate from you? Does it become like an alien part of your body that you are fighting?

FIELDS: At first, it felt like something had invaded me. Of course it’s my own cells that are doing that so there’s also the idea that it’s part of you. But my first response was definitely a kind of a warrior energy. I had to fight. After I had my first radiation treatment I would use mantra and visualization—particularly a wrathful deity visualization—to help destroy the cancer cells during the treatment itself.

TRICYCLE: Did your relationship to practice change when you were diagnosed?

FIELDS: It became more intense. My experience in practice is that the quality of your meditation deepens with the amount of time you actually spend. This isn’t a particularly Buddhist experience. There’s a quote—I think it’s Samuel Johnson—something about how death wonderfully concentrates the mind because you start to look at things and you know it’s not a question of “When I get this done” or “When this happens, then this will happen.” It’s right now. And that’s what practice seems to be about, continually bringing you back to right now.

TRICYCLE: Did you literally start spending more time each morning practicing? Or did you do what you had been doing with greater concentration?

FIELDS: It was with greater concentration and with greater regularity. I would sit every morning, pretty much no matter what. And I felt that it didn’t matter how long I was sitting, as long as I could connect with my practice on the spot. But the practice doesn’t change because I have cancer. The same things happen as happens with anybody’s practice. You go in, you go out, you get bored, you have insights, you have good times, you have bad times. There is a sense of—not so much what’s important—but what’s unimportant. You look at the world and see people suffering over such silly things.

TRICYCLE: Has it affected your own behavior? Do you get caught up less in the petty, ignorant, and innocent ways in which we create suffering for ourselves and others around us?

FIELDS: Maybe. But I still have habitual patterns and delusions and illusions and I get sucked up into life. The deeper question then becomes what does it mean that I am going “to live until I die”? What does living mean? There seem to be at least two different ways of approaching this: either going into seclusion or continuing to be engaged in this socalled samsaric world. I keep working at my job. I keep up relationships. I keep a certain amount of writing going. I just keep on living. And part of living is very silly. There were times when I thought that I should just go into retreat and try to attain perfect, unsurpassable enlightenment before I die [laughter]. But at the same time, I felt like, “Wait a minute, if the whole idea is to live and I’m fighting this in order to live, then live fully.” And that’s what I chose to do. Whatever that means.

TRICYCLE: What do you do with self-pity?

FIELDS: I think self-pity comes along with self. When this first happened it felt like all my karma was coming and perching right on the tip of my nose, looking me straight in the eyes, staring right at me. And I was staring right back. That’s the warrior aspect. Shortly after I was diagnosed, Allen Ginsberg called and reminded me of something that Trungpa Rinpoche had said to Billy Burroughs (William Burroughs’s son), who had had a really hard life and was having a liver transplant. Rinpoche said, “You will live or you will die. Both are good.” I don’t want to make my death into the enemy. Death is not the enemy. Death is part of us, it’s part of our life. Cancer can be seen as the enemy—at different stages. But death itself, however it comes, or whenever it comes, is not the enemy. That’s something to be embraced. And that’s the true warrior’s stance as far as I understand it. For the warrior, death is not the enemy. When the samurai went into battle, they brought little purses that contained money for their funerals. If you go into a battle fearlessly accepting the possibility of death you have a much better chance of fighting well and in fact of winning, than if you go in scared. A lot of Buddhist and spiritual practice in general is aimed at removing the fear of our own death. The fear of our own death is the fear of our own births or the fear of our own lives.

TRICYCLE: I’m alive, you’re alive. We’re both living and we’re both dying. You have a diagnosis of cancer and I haven’t. What’s the difference? Are you dying more than I am? Does your situation make you more aware of dying while I am probably still functioning under the delusion that I am going to live forever?

FIELDS: Not that you are going to live forever, but the timing would seem somewhat different. I’ve been told that I’m in immediate danger. The exact timing is always in question. But when I saw a doctor at Stanford for a second opinion, I said, “Everybody has said this is incurable.” And he said, “Has anybody said to you ‘incurable’ does not necessarily mean ‘terminal’?” And I said, “No, nobody has mentioned that.” Lots of diseases are incurable or chronic but can be managed and are not necessarily terminal. But I’m living much more with a constant question mark. When I was in remission, the cancer was like a rhinoceros. Like off in your peripheral vision, there’s this rhinoceros with beady, ugly eyes and leathery skin and tsetse flies buzzing around it, like an evil unicorn. And that rhinoceros is more or less peacefully chomping on the swamp grass. And as long as the rhinoceros is chomping away, not noticing you, you’re fine and you’re in remission. But at any moment the rhinoceros could look around, go crazy and come at you. So you are always living with this rhinoceros, even when the cancer is supposedly gone or is in remission. So one difference is that I have this rhinoceros around.

TRICYCLE: Speaking of grass, have you used plants for healing?

FIELDS: Yes. In addition to allopathic medicine and complementary alternative medicine and visualization and meditation and cancer therapy support groups and psychotherapy and yoga—has been the occasional use of sacred medicinal plants in a healing context. The main medicine has been peyote and I’ve attended the Native American Church where it is used in the healing ceremony. And recently I did ayahuasca with a Peruvian shaman. During that time I was investigating my mind, looking for the fear of death, trying to track it down and face it—and I couldn’t find it. I don’t know if I didn’t have it or was ignoring it or had lost my edge or lapsed back into the illusion that everything is fine and I’m going to live forever. But out of nowhere came the verse from the Four Reminders:

Death is real,

Comes without warning

This body will be a corpse.

And I started repeating that Reminder. And we do need to be reminded. No matter what happens, you tend to forget. The fear is always about what’s going to happen in the future, but I’m sure if, at some point, they say the cancer is all over the place and there’s nothing we can do, I can’t say ahead of time what my reaction is going to be. And there’s nothing wrong with fear. We keep having these ideas about what is spiritually the right way to handle this, and that’s really unfair to people. They get this trip laid on them.

TRICYCLE: Like if you are afraid you’re not dealing with this in some spiritual way or elevated way or enlightened way?

FIELDS: Yeah, or there’s something wrong with it. But if I’m afraid, then I’m afraid. So what? Don’t be afraid of fear. Be exploratory. Go into it. How solid is it? It feels very solid because it makes people freak out but if you lean into the fear and investigate it, if you know what it is actually made up of these physical sensations, which, when you direct awareness to them, tend to lessen or dissolve. It’s made up of projections into the future about what’s going to happen or what’s not going to happen. So, with the arising of fear, practice can be a very powerful kind of aid to the whole spirit, to your practice. Don’t be afraid of the fear. Be curious.

TRICYCLE: What are your fantasies about the end of your life?

FIELDS: I have more fantasies about living than about dying. But I think I want to be as conscious as possible at the end. Realization becomes possible then because you have less external distractions and the intrinsically pure nature of mind daunts luminously at that point—supposedly. And the way to train is really no different than to train with your own meditation now. It’s not like there’s some big secret complicated yogic thing when you die, but when you practice meditation now, then you’ll be continuing to practice at the moment during death. I asked Lama Tharchin this question about painkillers, and he laughed and said that they aren’t a problem. For one thing, if you are feeling a lot of bodily pain it’s harder to practice and concentrate. And when the body and mind separate there is so much general confusion and chaos at that moment that it would be very difficult and not even very useful to keep your consciousness. And anyhow, your Buddha-nature has survived through countless lifetimes—the fires of hell, of drowning, God knows what. Buddha knows what. It’s survived. So a little morphine isn’t really going to affect your Buddhanature, don’t worry about it. The idea that Buddha-nature is unborn and therefore undying has been very helpful. So to practice with that as the ground, and that as the path, and that as the fruition seems to me the best thing to do. As for having fear, that’s just being a fearful buddha.

TRICYCLE: What do you believe happens after death?

FIELDS: I don’t know. I think I feel comfortable being agnostic about what happens or doesn’t happen after death. And I guess I agree with what Stephen Batchelor says about people who say the reason to practice is to get a better rebirth: it’s also not my experience. I practice to get a better life. Or to live this life as—not necessarily better, but as deeply, as fully, as joyfully as possible. And if it helps in life, I would assume it helps in death, since death is part of life, and dying is part of living.

TRICYCLE: Do you ever imagine the specifics of your death?

FIELDS: I’ve instructed Marcia about which particular teachers or spiritual friends or gurus l would like to have notified. Some yogic teachings say the best way is to die alone, because there is less distraction and less people projecting their fears and making a big circus out of the whole thing and trying to hold on to you. So, go to a cave by yourself and die like a deer in the forest. That has a certain attraction. But if it happens some other way, then it happens that way.

TRICYCLE: Do you know what you want to have happen with your body?

FIELDS: Do you?

TRICYCLE: I’d like a sky burial in Nova Scotia. To be laid out on a bluff over the St. Lawrence and fed to the eagles and ravens and coyotes and insects. Of course, that’s illegal. But that would be my preference.

FIELDS: I gravitate toward sky burial too, but cremation seems like a good alternative. But a real cremation like they do in India, where you get the wood and build a fire and put the body on it. Not so much for myself, but there’s something good about the visibility of the whole thing for other people. My ideas are influenced by Trungpa Rinpoche and his instructions that the body not be moved, or be moved, maybe once during the first three days because supposedly it takes that amount of time for the consciousness to fully leave and to understand what’s happened and so on. And ideally the body would be in the shrine room, laid out on a simple blanket on the floor. So then the body is there for everybody to see and people can come and practice with the body. And then there’s a particular kind of ceremony to do. And if somebody comes to do phowa [the transfer of consciousness through the top of the head] that’s okay, that would be nice. I don’t have a huge feeling about it one way or the other. I think it would be nice for people to have a party. As long as they had a good time. One fantasy I did have, like I said, that cremation, which again is sort of difficult in terms of the law—it would be an outside cremation, more or less like they do in India. You would have to put some ghee or oil or butter or something over the body, to make sure it burns well because then you can see what the body is made of and all that. You can hear it. You can smell it.

TRICYCLE: What can you offer others who are in a similar situation?

FIELDS: I have found myself in the middle of this whole conversation about alternative and conventional medical treatment. In some spiritual traditions, there’s a view that since everything comes from mind, everything can be cured by mind or by some kind of spiritual practice or positive thinking or faith. And then there’s the middle ground that says the mind and the body both influence each other. The other extreme pays attention only to physical medicine and material phenomena. I see too many people get caught in allying themselves with one extreme or the other. My experience is that everything can be medicine. For me, radiation and chemotherapy—at the right time and in the right way—can be medicine, even if some people say the treatments are really poison because they mess up your immune system. But if you’re dead, it doesn’t help you to have a healthy immune system. I see it as a whole continuum of things that can be used and should be used at different times in your fight or in your healing, however you want to approach it. You have to really investigate everything. Try it out, but don’t get caught in these boxes of “conventional” or “alternative.” These boxes are breaking down now but I’ve still seen a number of people die because they had some very fixed opinion about conventional medicine. It really is up to each person what they do and how they handle it.

TRICYCLE: In what way do you deal with anger or frustration about your condition?

FIELDS: There is no one way. It changes. One time as I was driving back by myself from a retreat, I just started weeping at a certain point. And that gave way to this tremendous explosion of anger and rage which came out. I just started screaming as loud as I could. And because I was in the car by myself, which for Americans is like a place of meditation and refuge, a cave, I was screaming at the top of my lungs, “Fuck you, cancer! Fuck you, cancer! Cancer, fuck you!” and ended up writing a whole poem called “Fuck You, Cancer” and that was a very powerful moment for me, just to be able to express that feeling.

It was anger at this thing that has come and has tried to take over my life. Making such a big deal of it, and putting it at the center of my life. It has to be kept in perspective, otherwise the disease has won in a completely underhanded way by taking over your life—by being what your life revolves around—when what you are fighting for is a life that is flexible and can respond in different ways. The central organizing principle is what you make it. It’s awareness or Buddha-nature, and certainly cancer can put that in sharp relief. But my rage was about realizing how much it had usurped my life.

TRICYCLE: What is the role of the caregiver?

FIELDS: In some ways, being the caregiver is more difficult than being the person who has cancer. The caregiver is like your shield bearer. I have been very lucky with Marcia. She made a vow to help me through this. She has accompanied me to every doctor appointment, taken notes, asked the tough questions, and organized what is a really a complicated military operation. Helping someone fight cancer is a really hard practice.

TRICYCLE: And helping someone die?

FIELDS: Trungpa Rinpoche emphasized just really being there with them. He talked about just being with the person in a genuine way and not laying a big trip on them. This is the most helpful thing that you can do. One of the most common trips that get laid on people is this idea that death is the enemy. If death is the enemy, then everybody is ultimately a failure, because they lose that battle if they see it that way. And particularly people battling with cancer or with any disease. If they see death as the enemy, then they feel that they have failed in this fight. Which is a tragedy for people to have that put on top of all of the suffering and the struggle that they are going through, to feel that they have failed or that they didn’t do enough, they didn’t do the right thing, that they didn’t eat the right low-fat foods, or didn’t drink enough wheat grass juice, that they didn’t uncover their shadow side, that they didn’t go psychologically deep enough, that they didn’t quit smoking. That they didn’t meditate enough, have positive enough thoughts, all the endless guilt-tripping that people can get into. The fact is that no matter what we do, how much we do, as the Buddha said, everything that is put together will come apart. Everything that is born will die. Meditation is partly about realizing that the mind is beginningless and therefore endless, open and luminous and deathless. But that has nothing to do with what happens to the physical body. The physical body does die. And that death is not in any way a failure. It’s a logical culmination of each life.

TRICYCLE: How did going into and then out of remission affect you?

FIELDS: When I went into remission, people talked about my miraculous recovery. But when the cancer came back, I had to approach it in a different way now. It became something I had to be able to live with. It came back in a lesser extent and in a more limited area, and wasn’t immediately threatening to my life, and so rather than use aggression, some kind of accommodation was called for. I was faced with a situation of coexistence. I added practices to my daily routine which emphasized the purification and strengthening of my own body and my own cells and so on, almost imagining the transformation of the cancer cells rather than the obliteration of them. Transformation into healthy cells, into healing cells. Maybe a cure will appear, but it hasn’t yet, so the strategy is to figure out how to coexist, how to keep it down to a level where it’s not life threatening. The other day I had a thought that I don’t have a life-threatening disease. My life is threatening my disease, in that it is keeping the disease from taking over. I live a disease-threatening life.

TRICYCLE: What is your prognosis?

FIELDS: That question again! The odds are not good. One hundred to one, I’m going to die. As to when, I’m not interested in fortune telling by either spiritual or medical seers. As I said earlier, I’ll live—and here I’ll add, as well, as deeply, as madly as I can—until I die. One thing, though, is certain, which this whole encounter has made very clear: the dharma is good in the beginning, good in the middle and—I’ll bet my last dollar—good in the end.

PETALS

I spilled the flowers

Pale pink petals

scattered on the table

startled

Funny

what can scare you

in this world

one day

pale pink petals

another day

three little shadows

gray-black petals

spilled, scattered

backlit on

the shiny film

there!

in the left lower lobe

I reach for—

your fingertips

pale pink petals

brush

my cheek

This world—

Funny

how

in the light of death

everything

shines!

—Rick Fields

August 25, 1996

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.